At Ankrom Moisan, our interior designers and architects bring both depth and breadth of experience to every project. That expertise allows us to support our clients throughout the full life of their buildings—from early programming and ground-up design through renovations and tenant improvements years later.

Because we know our buildings inside and out, we’re uniquely positioned to return as trusted partners when our clients’ needs evolve. Our architects often lead the initialground-up design, establishing the vision, systems, and structure. As the building matures and programs shift, our interior designers step forward to lead renovation work, ensuring the space continues to function beautifully for the people who use it.

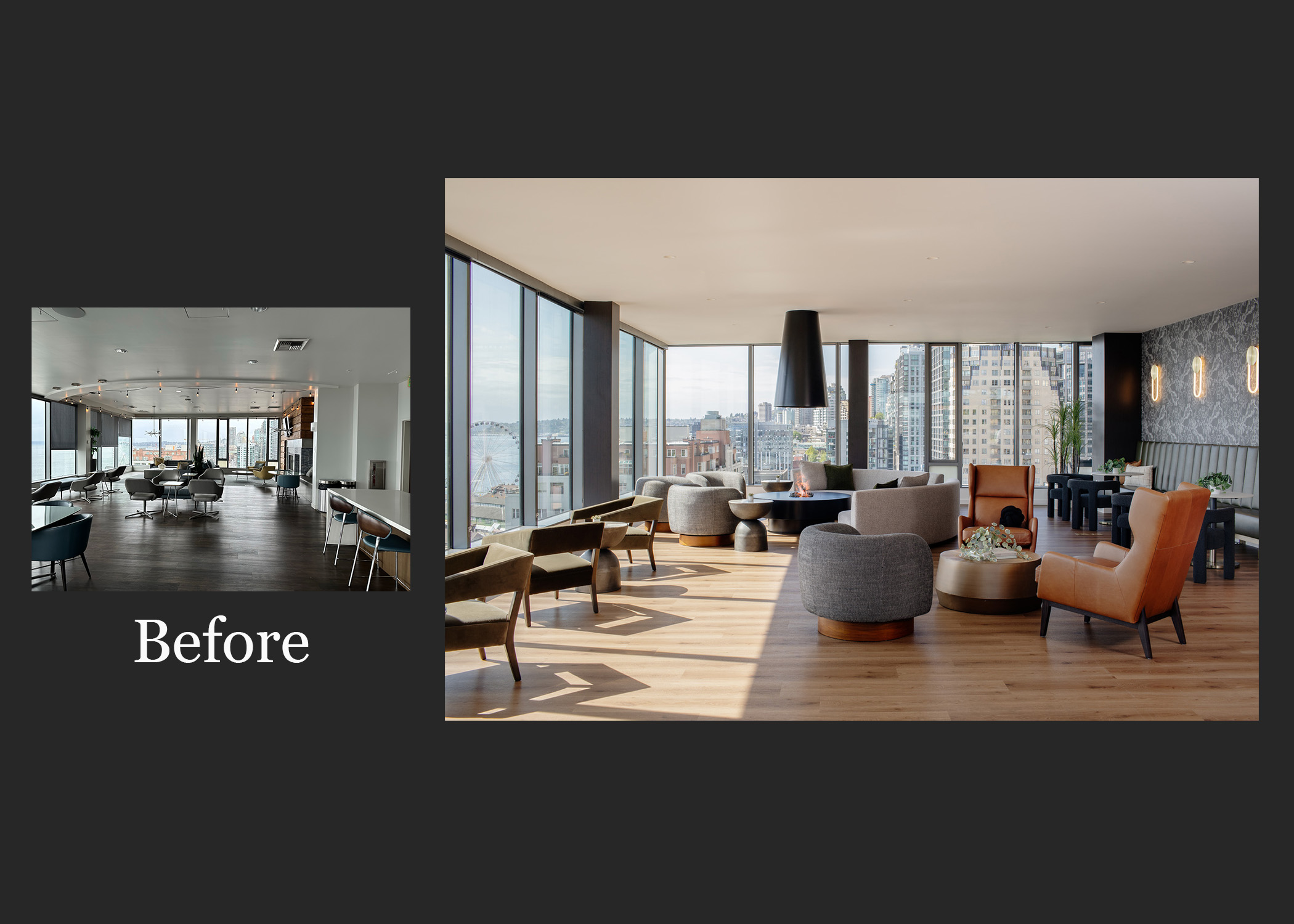

Griffis Seattle Waterfront

Across all studios, this collaborative model enables us to design not just buildings, but the entire lifespan of the environments our clients rely on.

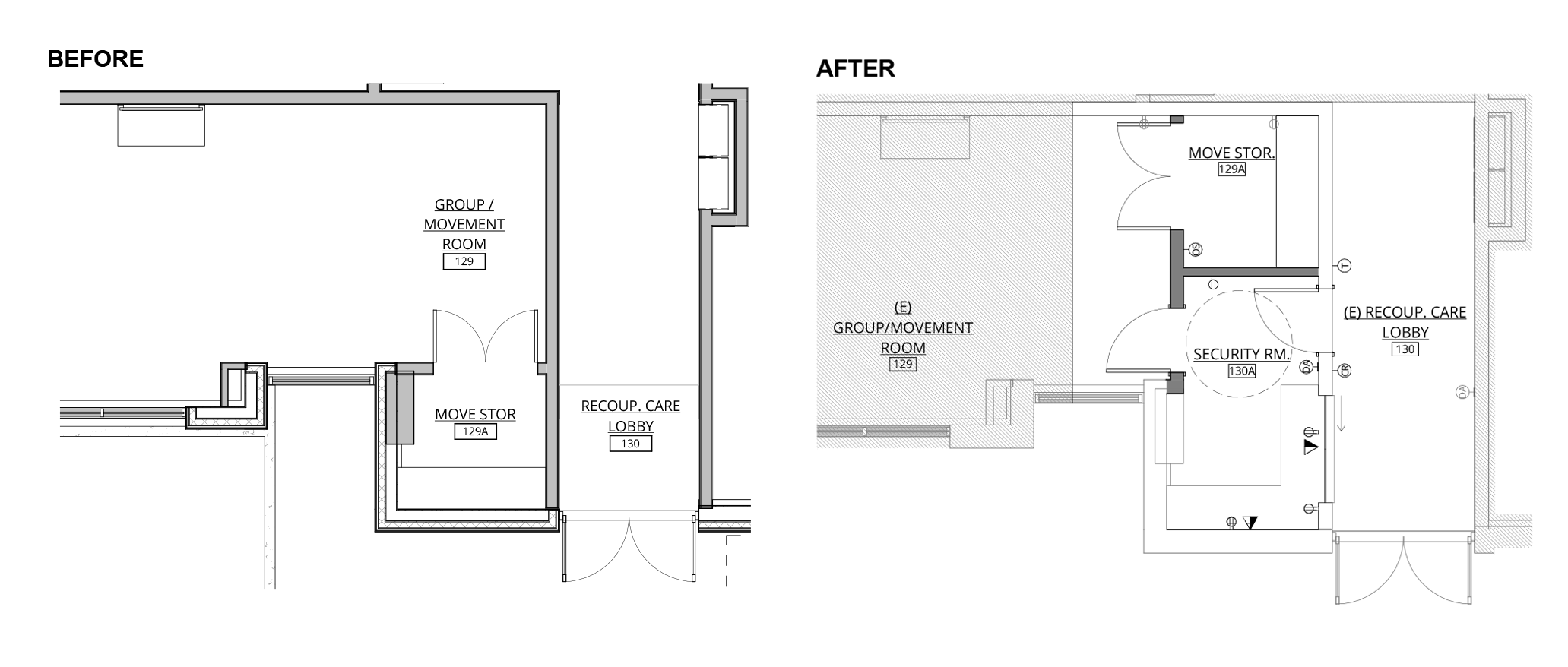

In 2016, Ankrom Moisan partnered with Central City Concern to design the Blackburn Center, which opened in 2019. From the beginning, the team worked closely with CCC to create a welcoming, stigma-free entry experience that avoided the institutional feel common in healthcare settings.

About six months after opening, CCC reached out again — this time to explore adding a security room that could enhance safety while preserving the building’s warmth and approachability. Because we knew the building intimately and maintained strong relationships with CCC’s facilities team, we were able to respond quickly, re-engage original engineers and consultants, and deliver a coordinated tenant improvement solution within just a few months.

Site plans from before and after CCC Blackburn Center’s hallway renovation

This project is a clear example of designing for the life of a building. As needs, leadership, and programs evolve, we remain a trusted partner ready to adapt spaces that support our clients and the communities they serve.

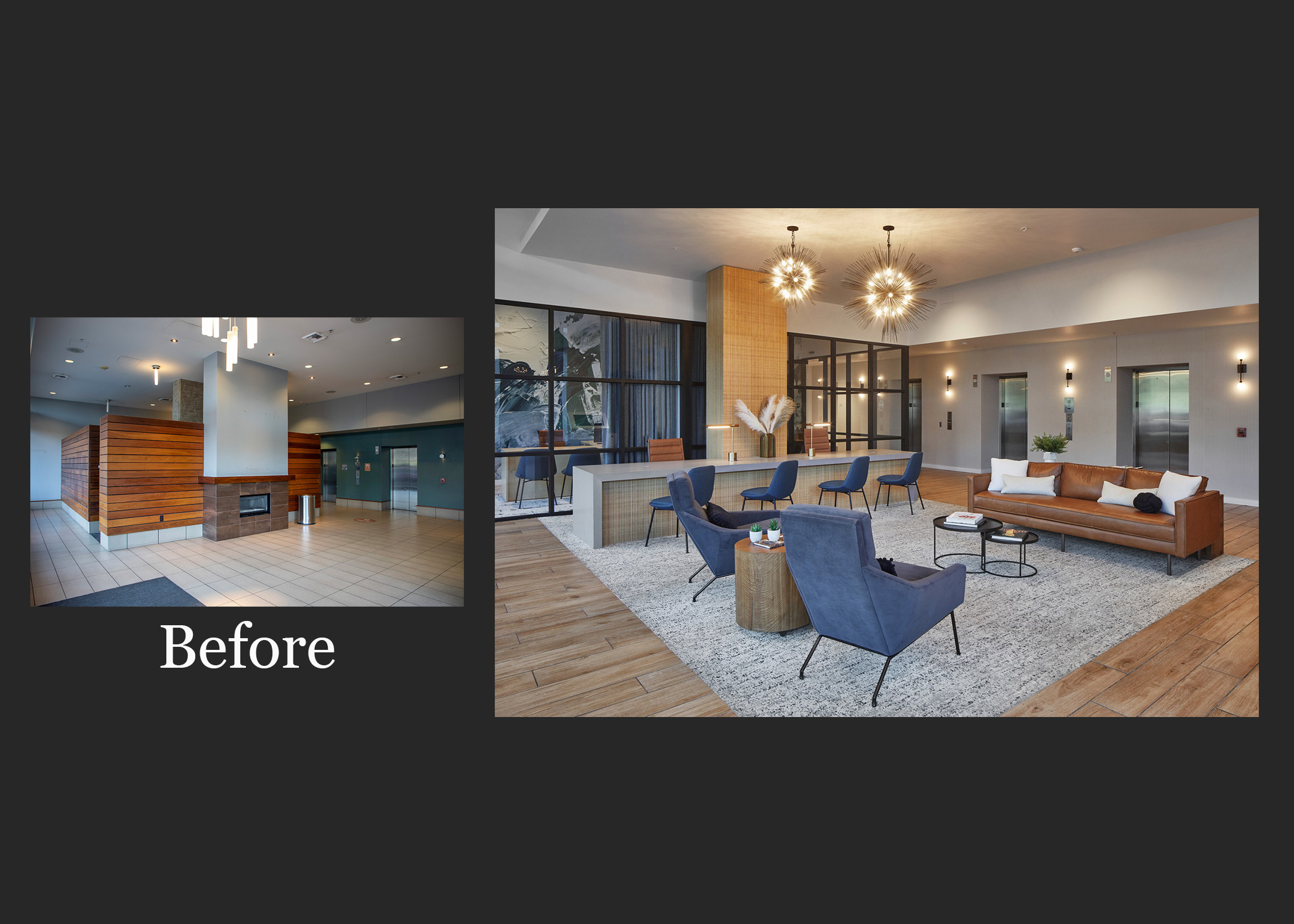

Our relationship with Trinity Terrace campus began in 2003. We served as the stamping architect for the Phase 2 City Tower, which opened in 2007, and our studio later collaborated with Mariah Kiersey to design the Phase 3 River Tower—a full CCRC with Skilled Nursing, Memory Care, Assisted Living, Dining, and Independent Living.

After River Tower opened, the AM team was invited back to refresh the common spaces connecting the original Phase 1 Terrace Tower and Phase 2 City Tower, aligning them with the design language of the new Phase 3 tower. We also updated the existing kitchen, dining areas, several amenities, and continued our collaboration with the Healthcare studio on the skilled nursing renovation.

River Tower

Because we knew the building’s systems and structure, we were able to re-engage many of the original consultants and streamline the renovation process. That continuity led to a more efficient design schedule and a smoother experience for the client.

Great buildings don’t stand still—they evolve.

We believe the most successful workplaces are those that adapt over time, staying relevant as organizations grow, shift, and reimagine how they work.

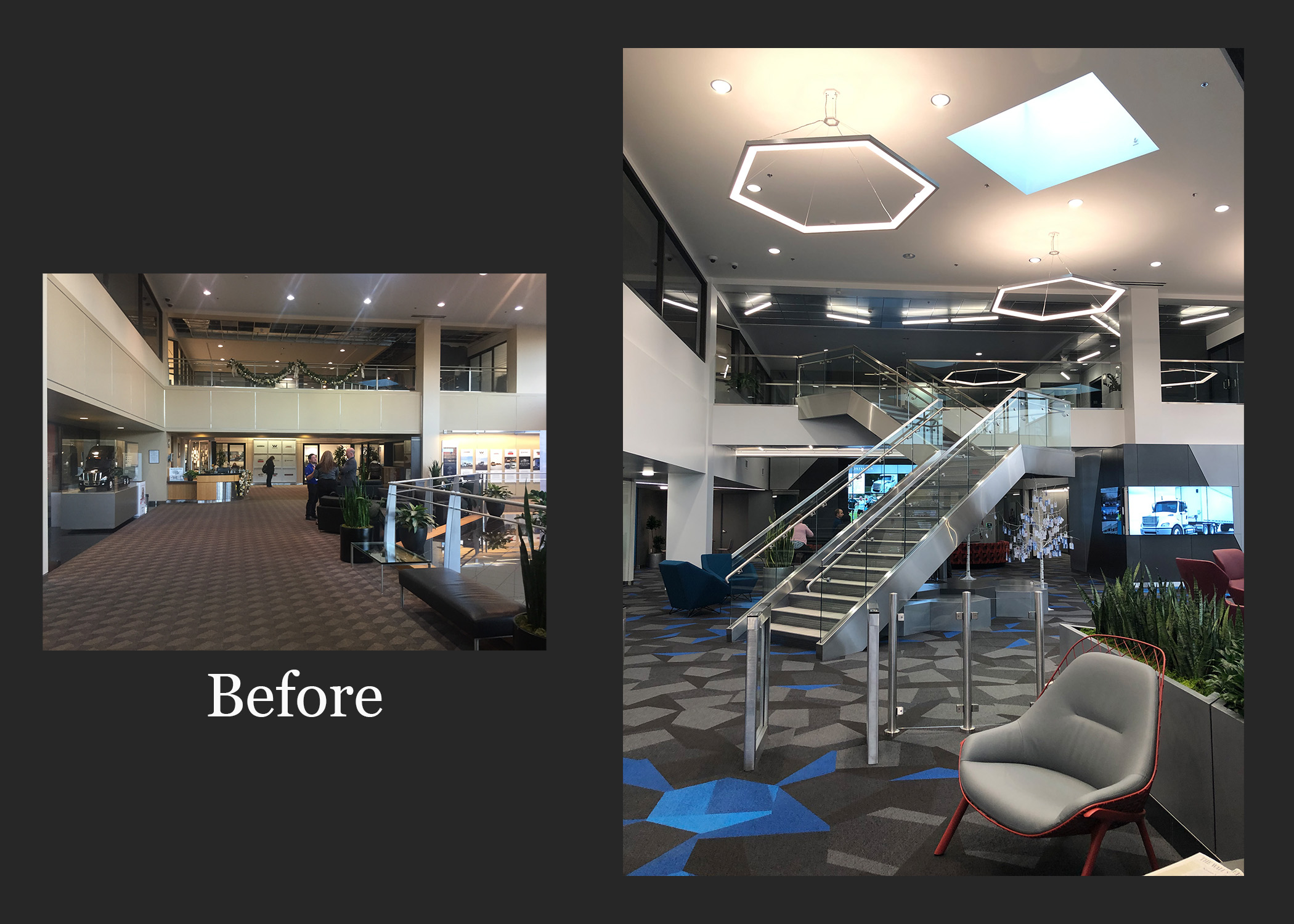

In 2016, our Office Studio designed the Daimler Headquarters campus. Nearly a decade later, we continue to partner with Daimler on targeted tenant improvements and security enhancements that respond to evolving business needs.

Because we know this campus inside and out, our renovation work is faster, more strategic, and deeply rooted in the original design intent—delivering high-impact updates with minimal disruption.

Daimler Headquarters

Our connection to the Peterkort Medical Office campus goes back to its beginning. Ankrom Moisan designed the original MOBs and parking garage, and that foundation has allowed us to stay closely involved as the campus has evolved over time. In partnership with Cushman & Wakefield, we’ve supported the full lifecycle of these facilities by expanding clinical services and enhancing the experience for patients, providers, and visitors.

Peterkort

From children’s clinics and internal medicine offices to outpatient care suites, elevator upgrades, lobby refreshes, and exterior canopy improvements, each project builds on the one before it. Because we know these buildings inside and out, our team can move quickly and deliver renovations that feel seamless, integrated, and forward-looking. It’s a partnership rooted in trust and long-term collaboration and a great example of how we design for the life of a building.

Renovation work is complex and requires close coordination with owners, the construction team, and consultants. At this campus it is also a cross-studio collaboration with Mariah Kiersey and Bethanne Mikkelsen working together to support these ongoing improvements over many decades.

Along Portland’s South Waterfront, Griffis South Waterfront was reimagined to meet the evolving expectations of today’s residents.

Following a change in ownership, Urban Living by Ankrom Moisan returned as the original design team, utilizing competitive research and demographic insight to shape a vision aligned with Griffis Residential’s diverse resident mix of young professionals, families, and older adults.

The amenity strategy focused on adaptable, enduring spaces. New amenities were intentionally introduced, including a dedicated co-working environment, enhanced mail and package spaces, and a reimagined fitness and activity room that now extends seamlessly outdoors – expanding wellness beyond interior walls and supporting both movement and social connection.

Rather than incremental upgrades, the strategy intentionally added missing amenities – identifying underutilized square footage to expand the program, anticipate evolving resident expectations, and position the building to compete with newer developments.

By aligning experience with strategy, the renovation reinforces the building’s identity and demonstrates how insight-driven design delivers both resident value and long-term performance.

Griffis South Waterfront

Through projects like the CCC Blackburn Center, Daimler Truck North America Headquarters, Griffis South Waterfront and others across our studios, we’ve seen firsthand how thoughtfully designed buildings stay resilient and successful long after opening. As technologies, trends, and community needs shift, our renovation work helps each space grow right along with them.

Now that residents have moved into Meridian Gardens, the building will naturally evolve as their needs and programs take shape. We hope to continue partnering with Central City Concern as new opportunities for design support emerge.

Visit our Renovations Expertise page to see how we are highlighting renovation stories from all our studios and to learn how we can help your community evolve, whether we’ve partnered before or are just getting started or just curious to see what we do!

Designing Communities that Move People

With over 100 successful transit-oriented design (TOD) and podium projects completed across the West Coast, Ankrom Moisan has shaped vibrant, walkable, transit-connected communities that transform underutilized land into thriving mixed-use neighborhoods. Our expertise extends across scales – from strategic district-wide frameworks to detailed building design – with a track record of delivering catalytic projects for agencies like Tacoma Housing Authority, Hines, Clark Country Transit, and the City of Beaverton.

Our approach balances visionary planning with pragmatic execution. We begin with transit-adjacent development (TAD) opportunities and help them evolve into fully transit-oriented communities (TOCs) by integrating long-term growth strategies, inclusive public engagement, and equitable housing solutions. We don’t just design buildings near transit – we cultivate places where people live, work, and thrive without needing a car.

Our clients rely on us to:

Lead complex, multi-agency stakeholder engagement processes.

Maximize land value and development potential while preserving transit function.

Prioritize community needs through housing diversity and public realm activation.

Deliver cost-effective, code-smart podium solutions at scale.

To accomplish these goals, we’ve put together a list of five do’s and don’ts for designing successful, impactful transit-oriented developments.

DO Create Mixed-Use, Mixed-Income Neighborhoods. DON’T Build Monocultures that Ignore Economic Diversity

TODs should support a full spectrum of incomes and uses, from market-rate and affordable housing to live/work spaces, retail, and employment hubs. This mix increases transit ridership, reduces car dependence, and promotes economic vitality. Oliver Station in Portland is a standout example – it’s a mixed-use, transit-adjacent project that blends affordable and market-rate housing atop ground-floor retail, directly adjacent to the MAX light rail line. It reconnected a fragmented streetscape and brought needed density, amenities, and equity into a rapidly evolving neighborhood.

Aerial view of the mixed-use Westgate neighborhood in Beaverton, Oregon

DO Prioritize Public Engagement and Local Government Buy-In. DON’T Underestimate Community Concerns or Political Will.

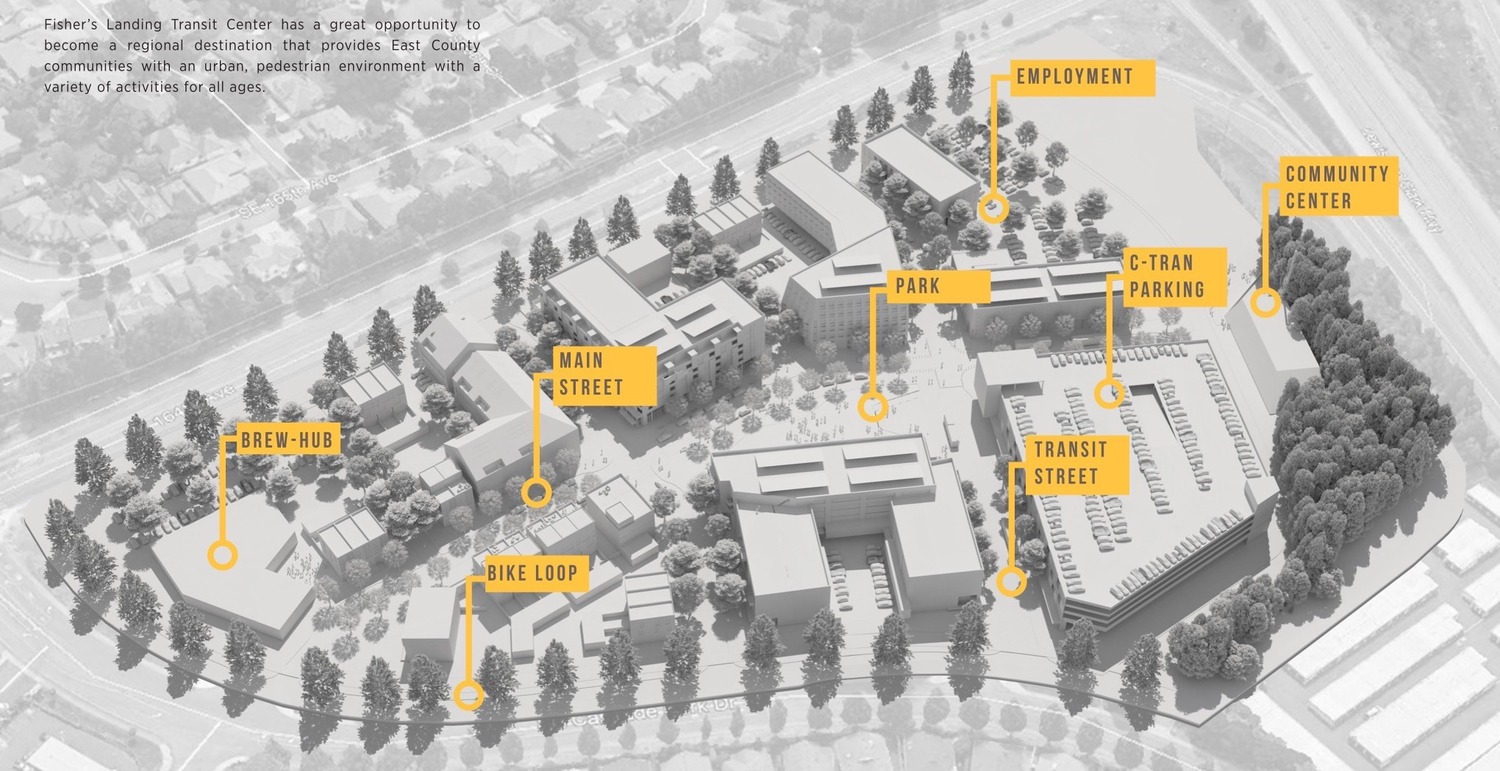

Early, sustained engagement reduces resistance and aligns stakeholders. At Fisher’s Landing, a robust outreach strategy informed a district-wide plan grounded in local values and transit requirements. We collaborated with the public, city leaders, and the transit agency to align development goals with long-term community interests, resulting in a flexible, phased vision that maintains transit operations while introducing new housing, amenities, and economic opportunity.

DO Design for Walkability, Safety, and Connectivity. DON’T Treat Transit as an Island.

TODs thrive when the pedestrian experience is seamless. Wide sidewalks, active frontages, street furniture, and visible transit connections are non-negotiable. Our Westgate framework plan in Beaverton placed a “100% corner” at the intersection of key pedestrian and transit axes, designing it as a vibrant focal point with active ground floors on all corners. This approach created a true urban node that strengthens both walkability and transit access.

Rendering of James Center North in Tacoma, Washington

DO Future-Proof Parking and Mobility Strategies. DON’T Let Surface Parking Define the Site.

Smart TODs transition from car-centric layout to multimodal systems over time. Through our mobility charrette at James Center North, we worked with local agencies to reimagine parking as a flexible urban element – initially essential, but adaptable to evolving shared mobility trends. Rather than relying on traditional fixed ratios, our plans allow parking to phase out in favor of programmable space, micro-mobility lanes, or active frontages as transit demand grows.

DO Activate the Public Realm with Purposeful Design. DON’T Leave Edges Dead or Space Underutilized.

Every surface counts in a TOD. Thoughtfully designed public spaces, transparent ground floors, and flexible plazas invite people to linger, connect, and return. The MacArthur Station project in Oakland is a prime example. Our design team created a central public heart at the BART station, anchored by active frontages, inviting walkways, and diverse open spaces that encouraged continuous activity and movement. Visual connections, lighting, and building orientation enhanced safety and navigability, while the public realm was designed as a true civic stage, welcoming residents, commuters, and visitors alike. The result is a fully integrated 8-acre community with 880 homes and 40,000 square feet of retail, deeply embedded in the region’s transit fabric.

Master Plan for Fisher’s Landing in Vancouver, Washington

Designing the Next Generation of University-Based Retirement Communities

University-Based Retirement Communities (UBRCs) are redefining what it means to age well by bringing together students, faculty, and older adults in vibrant, intergenerational settings centered on learning, wellness, and purpose. Projects like Mirabella at Arizona State University (ASU) have already proven how powerful this model can be, where residents live steps from classrooms, share campus amenities, and engage in daily university life.

Mirabella at ASU

At Ankrom Moisan, we see UBRCs as the next frontier of integrated design – where the combined expertise of our Senior Living, Healthcare, Workplace, and Housing/Higher Education studios creates holistic campuses that serve people at every stage of life. Building on what we learned through Mirabella ASU and across our four studios, we are exploring how to take this model even further: adding new layers of wellness, education, childcare, and housing that foster deeper connection and shared purpose across generations.

Each studio brings distinct strengths from healthcare planning and senior living design to student housing typologies, workplace wellness, and early learning environments. Together, we’re shaping campus models that function as micro-ecosystems for every age, where learning, living, and well-being are seamlessly intertwined.

A Paradigm Shift in Campus Living: Mirabella at ASU

Mirabella at ASU represents a true paradigm shift in how we think about aging and community. Rather than creating an isolated retirement tower, it established a vibrant, intergenerational environment at the heart of Arizona State University’s campus, where older adults, students, and faculty live, learn, and engage side by side.

This project redefined what a university-based retirement community can be. Residents aren’t separated from the energy of campus life; they’re part of it by attending classes, mentoring students, and sharing dining, wellness, and cultural amenities with the broader ASU community.

Mirabella ASU’s grab-and-go café

The next evolution builds on that foundation, imagining complete, integrated campuses that bring together fitness and wellness centers, childcare, healthcare access, dining, cowering, and shared gathering spaces in places that connect students, faculty, staff, and seniors in meaningful, everyday ways.

Mirabella ASU proved that aging in place doesn’t have to mean aging apart. It’s the model for a new kind of campus living as one build on connection, purpose, and belonging.

Bridging Generations Through Design: The Student Housing Perspective

Student housing design has always been about creating communities filled with connection, engagement, and belonging that help young adults learn, live, and grow together. Those same principles can seamlessly bridge generations when applied to UBRCs.

Imagine a twin-tower development, such as The Standard at Seattle, where one tower houses university students and the other is home to active seniors. The two are connected by a shared podium filled with vibrant, mixed-use amenities: cafés, fitness studios, classrooms, art and maker spaces, and co-working lounges. Each of those spaces would be designed for learning and social interaction. Shared outdoor terraces, dining areas, and recreation zones encourage spontaneous connection, creating a campus environment where age becomes secondary to curiosity and engagement.

The Standard at Seattle High-Rises

In this model, the building itself becomes the connector, blending academic residential, and social functions into one cohesive experience. Students gain mentorship, shared resources, and intergenerational friendships; seniors benefit from access to lifelong learning, energy, and inclusion.

The 818, another student housing project currently under construction in Tucson, Arizona, is a similar asset for students at the University of Arizona. It has a mixed program of student and workforce housing that share the same amenities—courtyards, co-working lounges, fitness spaces, and community rooms; all designed to bring people together. Even though The 818 isn’t a UBRC, it carries the same spirit: people from different walks of life living side by side, connected through shared spaces that encourage learning, curiosity, and community.

By drawing on existing student-housing typologies, such as flexible study lounges, collaboration zones, and integrated wellness amenities, the next generation of UBRC campuses can redefine what community looks like – vibrant, multigenerational environments that foster purpose, learning, and well-being for every resident.

Designing for Daily Life: The Workplace Perspective on UBRCs

A thriving campus community depends on the well-being of the people who live, work, and care within it. Our Office / Retail / Community Studio brings that understanding to every project in designing spaces that strengthen connection, balance, and retention for both employees and residents.

At the Daimler Truck North America Headquarters, our team designed an on-site daycare that became a cornerstone of the company’s employee experience. Providing childcare wasn’t just about convenience; it was about supporting people holistically and recognizing that when employees can see their kids during the day, they’re happier, more focused, and more likely to stay long-term.

The expanded daycare at Daimler Truck’s North American Headquarters

That same principle applies to university-based retirement communities (UBRCs) by integrating everyday amenities such as early learning centers, flexible workspaces, wellness studios, and community cafés. UBRCs can become places where generations intersect naturally by imagining a campus where a retired educator volunteers in the daycare, or where staff and residents share a morning fitness class or a coffee at the café. Those moments of overlap make the community stronger and more human.

Designing for intergenerational interaction is the next evolution of campus planning by taking lessons from workplace design such as transparency, flexibility, wellness, and access to services. When those lessons are applied to UBRCs, they can create environments that support everyone’s quality of life, from residents to caregivers to employees.

Integrating Health and Housing: The Healthcare Perspective for UBRCs

At the Central City Concern (CCC) Blackburn Center, we brought together healthcare, housing, and recovery services under one roof by creating a model where people can live, heal, and grow in an integrated setting. It’s a project that embodies the power of trauma-informed and human-centric design, connecting dignity, safety, and holistic well-being in every detail.

CCC Blackburn Center

In behavioral health and wellness design, connection and collaboration are everything for not only the people who use the space, but also for the many stakeholders who help shape it. For Blackburn Center, our studio worked closely with an extraordinary range of partners: clinicians, case managers, housing operators, state licensing agencies, and funders. Together, we developed a program that met people where they are, responding to the real needs of those navigating recovery, housing instability, and health challenges.

The Blackburn Center was a complex puzzle, combining a federally qualified health clinic, substance use recovery programs, short-term housing, long-term studios, and supportive services within one facility. Each group had distinct needs and operational priorities, and our challenge was to weave them together while maintaining safety, dignity, and belonging.

Our design focused on supporting different levels of care and wellness through shared amenities: community kitchens, large resource area with teaching kitchen, yoga spaces, clinic, urgent care, pharmacy, gathering spaces, and multiple outdoor terraces. These spaces foster connection rather than separation. Keeping these populations together was intentional – it reduces stigma and reinforces that healing happens through community.

For future UBRCs, that same principle applies. Integrating healthcare and housing on one site ensures residents have access to care before a crisis occurs, while promoting engagement and wellness across generations. At the Blackburn Center, we learned health, housing, and community are inseparable and that the model of integrated care and shared amenity spaces where they intersect can translate beautifully to UBRCs where physical and emotional well-being are equally prioritized.

What makes the next generation of university-based retirement communities so exciting is the opportunity to merge expertise across markets – to think beyond traditional senior living and design campuses that truly serve the full spectrum of life.

The Integrated Future of UBRCs

At Ankrom Moisan, our Senior Living, Workplace, Healthcare, and Housing/Higher Education studios each bring a unique perspective, but together they share one common goal: to design communities that foster connection, purpose, and well-being. From hospitality-inspired living and intergenerational engagement to on-site healthcare, early learning, and student-driven social spaces, these campuses can be vibrant ecosystems where people of all ages live, learn, and thrive together.

Our experience designing projects like Mirabella at ASU, Daimler Daycare, CCC Blackburn Center, and The Standard at Seattle has shown us that successful communities don’t just meet people’s needs; they evolve with them. The future of UBRCs lies in integration – blending living, learning, working, and wellness into places that feel human, connected, and alive.

As we look ahead, our vision is clear: to help universities and their partners design campuses that blur generational boundaries, celebrate lifelong learning, and embody the next chapter in community design where every space supports growth, belonging, and the shared experience of living well at every age.

Approaches to the Design Process that Can Help Push Multifamily Projects Toward Construction

As nearly a billion dollars of bond money was invested in affordable housing projects in the Portland-metro area, architects are finding paths to success. Commenting on what jurisdictions can do to encourage housing development, Don Sowieja, Principal, shares his thoughts on how different approaches to the design process can help push multifamily projects toward construction.

“The city of Portland has taken major steps to encourage development,” Don said. One of these steps was consolidating permitting functions into a single bureau: Portland Permitting & Development. “Prior to that shift in policy organization, you might expect three to four months before you go your first round of plan review,” he continued, adding that it now takes around six weeks.

According to Don, when it comes to overall timeline for a project, the design process is critical.

Simplify the Design Process

“One of the things we’ve found is to keep it simple,” he said.

“Keeping a basic layout and overall composition allows a project to move through the process more quickly,” Don claimed. “Oftentimes a proposal’s details may be unclear to city staffers, so it’s important to keep an open line of dialogue with them to navigate the approval process.”

“The simpler the design, the simpler the compliance,” he said. For multifamily housing, unit size and type matter. “If you have three unit types – studios, one bedroom, and two bedrooms – and you have one of each of those unit plans, that’s as easy as it gets for the city to understand, as well as for the developer to demonstrate compliance,” Don said.

For projects subject to design review, Don encourages teams to know the rules and follow them. “It’s right there on the page,” he said. “Reading and doing what it says is the best way to move quickly through a subjective process.”

Project rendering of Pepsi Phase B, an inclusionary housing project in Portland.

Embrace Inclusionary Housing

Although inclusionary housing is relatively new to Portland, many cities on the West Coast have similar criteria. In Portland, inclusionary housing requires all residential buildings proposing 20 or more new units to provide a percentage of them at rents or sale prices affordable to households at 80 percent of the median family income or below.

“Development teams should embrace the fact that it is a requirement for multifamily projects,” Don said. “While there was some concern at the outset of this new requirement, most of the development community has figured out that it has a financial and organizational impact.”

According to Don, demand for multifamily projects has declined in the past 2.5 years, following a roller coaster of economic cycles, including the COVID-19 pandemic, inflation and interest rate increases. However, that has begun to change in 2025.

“The design side is really picking up,” he said. “That takes a while to translate into construction starts, and construction is the big money and the larger economic driver.”

Hopefully, once the industry’s efforts shift toward construction, we will see more architects working with jurisdictions to simplify or streamline the design process to increase housing, and more developments being made to meet the need for affordable housing throughout our cities.

How Jurisdictions can Encourage Housing Development

When it comes to encouraging the development of housing projects, there are a handful of things that jurisdictions can do to support architects and designers, streamlining the process of design and construction from start to finish.

Our projects outside of Seattle, Canopy and Modera Shoreline, benefitted from an accelerated project timeline, a result of the City of Shoreline’s collaborative approach to streamlining the design review process.

Project rendering of Modera Main Street

In the last 10 years as urban affordability and quality of life have become issues to residents, developers and investors have looked to new submarkets for development. Sharing its southern boundary with Seattle, the city of Shoreline has been recognized as one of the area’s fastest-growing residential hubs.

After listening to developers, the city set about enhancing its portals, attracting brand retailers, planning for future TODs, codifying development incentives around sustainability, and streamlining their entitlement and permitting processes. Amidst the challenging economic times of the last two years, three developments alone – Shea’s Canopy and Verdant, and Mill Creek’s Modera Shoreline developments – have created more than 1500 units, demonstrating that a jurisdiction’s focus on encouraging development can have transformative impacts.

Canopy

A motivated jurisdiction can work with the development community to create the vibrant city desired by its constituents. There are several ways this may come to fruition.

Reducing Permitting Timelines

Bypassing Design Review and MUP milestones could yield significant time and cost savings on project delivery, expediting the approval process and speeding up time to construction.

In 2023, the Seattle City Council amended the land use code to make two important changes to the design review program aimed at encouraging additional low-income housing.

The first change permanently exempts low-income housing projects from the Design Review program.

The second change provides a new Design Review exemption for projects that meet Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) requirements by providing units on site via the Performance Option under the Land Use Code.

Due to this change, projects that opt into the Performance Option can skip MUP and Design Review and proceed directly to Building Permit where land use code compliance will be evaluated concurrently with other review subjects.

The impact of this shift is an accelerated timeline for projects to go from design to construction, and as a result, an increase in the number of housing projects being made.

Typically, the design review board can take anywhere between three to nine months to approve a project. During this process there are application fees to be paid by the applicant, as well as other payments made to parties such as land use attorneys who determine jurisdiction or design professionals who prepare and present the information to the review board.

Reducing the permitting approval and design review timeline for a single building translates to more time that can be spent on additional housing complexes, boosting the total amount of available housing in Seattle. It also means less money is spent on a project overall through the extra costs associated with presenting a project to the design review board.

This is just one example of how bypassing Design Review and MUP milestones could yield significant time and cost savings on project delivery. A full synopsis of the impact of reduced permitting timelines can be found here.

Lowering Impact Fees

Impact fees – also called system development charges in some places, like Portland – are the method cities use to collect funds that expand or provide infrastructure to support developments that are going through the permitting process.

These fees cover everything from sewers and transportation to parks and schools and are used to either fund the construction of those services, or the maintenance and expansion of existing infrastructure. Essentially, they’re a city’s way of generating revenue to maintain the services and infrastructure that are needed for a project that is being built.

Based on a per-unit cost, impact fees, along with review and inspection costs, can end up costing a lot more than a simple permit review fee.

To encourage more developments, impact fees can be reduced or lowered. Recently, the city of Portland completely waved those charges until 2028, making it both cheaper and easier to initiate new construction developments within the city. The impact is so large that some projects currently in development would not be able to move forward at all, if it weren’t for the Portland SDC moratorium.

Project rendering for Sandy Pine

Clarifying Code Language

The Portland City Council temporarily lifted restrictions on building heights for housing projects in specific planned districts at the beginning of 2025, a decision that will remain in effect until 2032. On top of changes to code language surrounding building heights, there were also adjustments to minimum lot sizes on single-family dwelling lots.

“These amendments will help spur development to increase housing density, use land more efficiently, and create more affordability,” said Don Sowieja, Principal. “This limitation on height within the urban growth boundary for development has been very frustrating for developers. Hearing about this adjustment opportunity is a tremendous step in the right direction.”

Another somewhat recent code change made by the International Code Council provided significant updates to accessibility clearances, based on a study of wheelchair users. While the overall impact of the code change on buildings was modest/minimal, only expanding a few rooms by a few inches, the impact on impacted users was immense.

From a designer’s perspective, code changes can lead to added complexity, especially for considerations like accessibility. However, by clarifying the language around some of these codes, the design and construction process can be simplified and streamlined, leading to quicker project completion and more housing development overall.

For example, the city of Shoreline provides the Deep Green Incentive Program, which is an opportunity for development to meet certain sustainable development and construction certifications. If met, the city provides developers with increased flexibility regarding development code criteria, such as allowing additional building height, reduced parking requirements, and other substantial cost or yield impacts. Additionally, this incentive program allows jurisdictions to provide preferential treatment during the building permitting review process, fast-tracking approval and construction.

Extending Permit Life Before Expiration

Every jurisdiction has time limits for the permit review process. If there is no movement, a permit can expire, causing the project to have to restart the permitting process, adding additional costs and a prolonged timeline for a project to reach completion.

For both the city as well as developers, it’s important to keep a timeframe on project development, since it helps people plan for future projects. For example, financial transactions like loans only take place once a permit is approved. Since loan repayments need to be budgeted out over time, having that timeline shifted can obviously throw a wrench in any pre-decided plans.

Issued permits also have lifespans. Drawing them out is one way to prevent permits from expiring before a project begins construction, leading to more completed projects overall.

Jurisdictions have realized that there’s a benefit to keeping the development community engaged throughout the permit review process. Desiring to keep people involved, rather than pushing them out, jurisdictions are reaching out to applicants, offering permit extensions if formally requested.

With that change, permits can sit for longer periods of time before they have to secure/receive funding. These longer pauses come with the hope that conditions will soon shift in favor of developers, leading to more developments.

Moreover, as time passes, code and design review criteria change. Essentially, by extending permit life beyond expiration, the efforts of going through the permitting process are retained, and developments are encouraged, rather than given hoops to jump through. If permits last longer, these projects have the potential to save time and money by avoiding being re-tooled to pass review again if a previous permit expired.

All in all, these four examples of incentivizing construction and flexibility in the design review process are excellent options for jurisdictions to take advantage of in order to encourage new building developments.

Bridging the Belonging Gap

As student populations grow and on-campus housing remains limited, off-campus housing has become a critical part of the higher education experience. According to Propmodo, the demand for student housing greatly exceeds supply at many universities, making the asset class an unlikely real estate kingmaker over the past two decades. But this growing reliance has brought on new challenges.

While the first-year dorm experience is often rich in social interaction and university programming, the transition off campus can come with a steep decline in connection, support, and engagement. A column in The Daily Gamecock, the University of South Carolina’s student newspaper, put it plainly: “Off-campus housing can be isolating.” When students move off campus, they risk losing the daily rhythms and casual relationships that make college life feel cohesive. This raises a fundamental question for developers and designers alike: How can we ensure off-campus housing supports, not undermines, a student’s experience and well-being?

Putting Connection First in Off-Campus Housing Design

The best off-campus housing doesn’t just provide a place to live, it creates the conditions for connection. At VERVE West Lafayette, developed by Subtext near Purdue University, that philosophy takes center stage. Every detail of the building reflects Subtext’s broader “Unlonely Mission,” a commitment visible across other recent developments in Bloomington, Boise, and Columbus. All elements of the project are shaped by a singular mission: to unlonely student life. This shows up not just in the operations, but in the physical spaces themselves.

Verve West Lafayette

From the moment residents arrive, they’re greeted by a friendly team member at a vibrant leasing bar that doubles as a coffee spot by day and transforms into a social lounge by night. Upstairs, amenities include wellness-forward features like a yoga studio, sauna, and meditation spaces that prioritize mental health without feeling clinical. A bold design move, like a swirling slide connecting two floors, adds a touch of playfulness and sparks spontaneous interaction among residents.

There’s also an intentional balance between private and public. Study pods provide a quiet retreat, while common areas offer room for collaboration and friendship. Local design cues, from materials to murals, tie the space to the community to help students feel rooted in both place and purpose. And with a walkable location just minutes from Purdue’s campus, VERVE keeps students close to the heart of university life, even when they live beyond its footprint.

Design Strategies to Build Belonging Off-Campus

Creating a sense of belonging is essential for student success and well-being, especially in off-campus housing where students can feel socially and physically disconnected. Design plays a pivotal role in bridging this gap by encouraging interaction and fostering inclusive communities. Layered communal spaces like study lounges, community kitchens, maker spaces, fitness areas, and rooftop terraces support both structured and sporadic engagement. Semi-private “threshold” areas, such as shared entryways, floor lounges, or front porches, can facilitate passive interactions and foster the formation of micro-communities.

Verve Bloomington

Attention to scale and proximity is also essential. Breaking down large buildings into smaller “neighborhoods,” for instance, clusters of units sharing a lounge or “pods” with common amenities, helps cultivate a more intimate residential experience. Circulation spaces should be designed to encourage visibility and activity through features like open stairwells, transparent walls, and generous natural light.

Additionally, inclusion must be embedded from the start. Universal design features, like all-gender restrooms, multi-faith meditation rooms, and accessible layouts, signal that every student is welcome. But belonging also comes from the process. Early engagement through participatory design workshops, such as collaborative charrettes that use storyboarding, spatial mapping, or card-sorting exercises, can reveal latent needs and values.

Beyond the initial phases, ongoing feedback loops, through student advisory panels or milestone surveys, ensure that evolving expectations are acknowledged. Post-occupancy evaluations offer valuable insight into what worked, what didn’t, and what students wish had been included, providing direction for future projects. Partnerships with Student Affairs can surface less-visible insights, especially for underrepresented grounds, and collaborating with departments such as housing, DEI offices, or cultural centers helps ensure the design reflects the full spectrum of student experiences.

Verve Boise

The building’s location and its access to campus and neighborhood matter just as much. Well-lit walking paths, secure bike infrastructure, and proximity to transit support easy movement, while ground-floor retail or community-facing programming can integrate student housing into the fabric of the neighborhood. Visual and programmatic links to campus, views of landmarks, spaces for student orgs, and campus-branded graphics reinforce psychological connectivity. Ultimately, off-campus housing that offers informal third spaces, integrates wellness through design, and supports events like shared meals or club meetings becomes more than a place to live – it becomes a platform for unity, identity, and student growth.

A Call to Align

For the growing number of students living off campus, the line between inclusion and isolation often comes down to how their housing is designed. Developers, designers, and campus leaders must work together to meet students where they are, both physically, socially, and emotionally.

Off-campus doesn’t have to mean disconnected. In fact, with intentional design, it can be a powerful extension of campus life. By aligning priorities and centering connection, we can ensure that student housing continues to support, not interrupt, a student’s college journey.

Upgrading the Office Bathroom

Remote and hybrid work has reshaped employee expectations around basics. At home, employees enjoy a certain level of control. They set the soundtrack, choose the dress code, and move easily between professional and personal tasks—brewing coffee, folding laundry, or stepping into a bathroom that feels comfortable and private.

The office doesn’t offer the same ease. Restrooms shared with unfamiliar colleagues often feel sterile or impersonal, rarely matching the comfort of even a messy bathroom at home. And in a workplace culture where employees are weighing the value of commuting in, these details matter.

Restroom design may not top the HR agenda, but its impact is real. When such a basic daily experience is better met at home, employees are more likely to stay there.

A More Inclusive Office

Restroom design is emerging as a quiet but powerful influence on workplace inclusivity and wellbeing. Beyond basic function, these spaces can provide the privacy and accessibility needed by employees managing anxiety, digestive conditions, or chronic illness, as well as those who rely on mobility aids. Designers who have personally navigated workplaces in a wheelchair often describe how that experience reshaped their perspective — reinforcing the need to go further than ADA minimums and create spaces that feel genuinely comfortable and dignified.

Inclusivity also extends to gender. Many offices are moving away from traditional layouts, introducing shared sink areas with private stalls to better support a wider range of users. These shifts, paired with a hospitality-inspired design approach, signal a broader recognition: every detail of the workplace contributes to how people feel about being there. For employers, landlords, and building owners, upgrading restrooms is not only an investment in health and equity, but also a way to differentiate. And as office attendance climbs, these small but meaningful improvements can make returning to the workplace feel far more welcoming.

Better Bathrooms for All

On top of better privacy and cleanliness, companies and employees are also looking for aesthetic upgrades.

Restroom at the Swedish Medical Center Ambulatory Infusion Clinic

Once treated as purely utilitarian, office restrooms are being reimagined as part of a larger shift toward wellness-driven workplaces. More than a functional stop, they now serve as quiet, flexible spaces where employees can freshen up between meetings, take medication, wash up after a walk, or simply step away for a brief mental reset. In an environment where most spaces are shared, the workplace restroom offers a rare slice of privacy — and that small but meaningful distinction is what makes it one of the most human-centered elements of the modern office.

Lighting is super important in restrooms. If you’re working all day, you kind of want to just take a break, it’s kind of a reprieve. We’re starting to see lounge areas return in restrooms, like a nice chair where you can just go and sit, that kind of doubles as like a quiet space.

Think “Bathroom Selfie”

As companies reimagine workplaces to encourage people back into the office, many are drawing inspiration from hospitality—creating spaces that feel more like hotels, libraries, or members’ clubs. One area that is often overlooked, but deserves equal attention is the office restroom.

One cultural shift that proves the relevance of the workplace restroom is the bathroom selfie. For more than a decade, social media has been filled with snapshots from stylish hotel and restaurant restrooms. Now, even office bathrooms are joining that conversation, reflecting a broader awareness that every detail of the workplace experience matters. Even the most private spaces shape how people feel at work.

People like to take them. They like to go to a really curated experience, but especially to bathrooms because that’s where you can have a lot of fun. It’s a small space. People have privacy in there.

The Bathroom at Harder Mechanical

When people began to return to work after the pandemic, bathroom upgrades were focused on safety, sanitation, and preventing the spread of germs.

Post-pandemic, it was all about how we can make the restroom safer, and so that was a lot of automated doors and even sensors for when people go into the bathroom. It would alert you externally if somebody was in there. We went from that to all the way up here. The expectation for restrooms is unbelievable.

While words like “fun” or “inspirational” aren’t typically used to describe the office bathrooms, it seems like that is the direction many bathroom upgrades are moving.

The Timber Advantage

Our built environment is one of the planet’s biggest polluters, with buildings responsible for roughly 39% of global energy-related carbon emissions, 28% of which are operational and 11% from building materials and construction alone.

While this is certainly not a revelation, the window for meaningful change is closing fast. The need for architecture, design, and construction solutions that don’t just check the sustainability box, but actually move the needle — achieving sustainability goals, enhancing durability, and sustaining economic growth — has never been more pressing. The salve? Mass timber.

Now gaining momentum across the Pacific Northwest with large-scale developments like Portland International Airport’s nine-acre mass timber terminal, the region is emerging as a global leader in sustainable construction innovation. Surrounded by some of the country’s largest timber resources, the Pacific Northwest is well positioned to shift development to mass timber — unlocking a scalable, high-performance solution to not only reach sustainability goals but enhance durability and sustain regional economic growth.

C-TRAN’s newly completed campus expansion in Vancouver, Washington, includes a mass plywood operations building.

The Case for Mass Timber

Despite its long history, mass timber — a building material made from multiple layers of wood — has yet to see widespread use due to factors like the high premium on base material costs, perception and restrictive code requirements.

Once a common construction material, mass timber was largely phased out during the 20th century in favor of concrete and steel. Concrete, for example, offers flexibility for cellular layouts; it is, however, notoriously slow to construct, cold to the touch and contributes significantly to atmospheric carbon. As the world grapples with the negative environmental impact of traditional building materials, mass timber is making a comeback, and so are the myriad benefits it possesses.

Mass timber is more than just a sustainability win — it’s an investment in both pre- and post-construction efficiency, resilience and well-being. Its ability to streamline project timelines, reduce soft costs for time on-site, enhance durability and aesthetics, contribute to healthier environments, support regional economies, and aid in reducing the industry’s significant carbon footprint makes it a powerful tool for the future of sustainable construction.

Sequestering Carbon

Mass timber offers significant environmental benefits, notably in its ability to aid in reducing carbon emissions. Wood is the only scalable building material that sequesters carbon, carrying the potential to aid in reducing the building industry’s significant share of carbon emissions production by 14-31%.

Mass timber also requires less energy to produce compared to traditional building materials like steel and concrete. This reduced amount of energy demand aligns with the Living Building Challenge and LEED life cycle analysis criteria. These advantages allow the industry to substantially respond to climate change and its currently massive carbon footprint.

The material also offers an opportunity to improve forest health — it can be produced from thinning, less commercially desirable trees, creating more space for healthy, strong trees to thrive. This further enhances mass timber’s carbon sequestration efforts and supports the long-term vitality of forests.

Strength, Comfort, and Well-Being

Highly durable and energy efficient, mass timber boasts impressive fire resistance and the ability to withstand extreme temperatures. Unlike traditional lumber, which has a low fire rating, mass timber’s massive panels char on the outside during a fire, forming a protective outer layer that helps retain the building’s structural integrity.

Mass timber’s multi-layered panels provide strength without added weight, allowing it to be constructed on confined sites. Furthermore, the material’s low thermal conductivity offers warmth and comfort not found in concrete or steel, making it a unique and durable choice for modern construction. Combined, these characteristics enhance safety and durability while also contributing to occupant well-being, creating spaces that feel secure, stable, and naturally comfortable.

Mass timber’s advantages go beyond performance and resilience, however. While its structural benefits are undeniable, the material also enhances the experience of a space. The natural warmth and elegance of wood evoke a sense of comfort and connection to nature, aligning with the growing demand for biophilic spaces. The material enhances the visual environment while contributing to a healthier atmosphere, improving the well-being of those who inhabit and frequent these spaces.

The Standard at Seattle’s Cross-Laminated Timber (CLT) building is connected to two high-rise towers via a pedestrian corridor.

The Financial Upside

Although the base material cost of wood is currently high, savings from shorter project timelines, reduced onsite labor, lower import duties, and other operational efficiencies can offset the initial premium. Additionally, mass timber performs better thermally, further enhancing its long-term cost-effectiveness.

Often sourced and produced locally, the transportation and storage costs of mass timber are also minimized. The prefabricated nature of the material allows for quicker assembly, yielding less soft costs related to project management, street closures, and material storage. This streamlined construction process, in turn, allows for earlier occupancy and a quicker return on investment.

Shifting to mass timber development also carries the potential to boost rural economies by generating demand for sustainable forestry. Supporting local wood producers and creating jobs in these communities helps stimulate economic growth and balance wealth distribution between urban and rural cities and towns in timber country, encouraging a more sustainable and equitable approach to development.

This combination of cost savings, improved efficiency, and economic empowerment is an attractive incentive to developers, architects, and communities seeking to balance financial viability with sustainability goals.

Mass timber offers an impactful, multi-faceted solution to the urgent challenges of sustainable development, and a shift to mass timber can address the growing demand for more environmentally responsible building practices.

From significantly reducing the industry’s carbon emissions to promoting healthier environments and fostering economic growth within communities, it supports a more sustainable construction process and offers long-term benefits that surpass traditional building materials and approaches. It should be the baseline assumption for every new development, creating a lasting positive impact on the future of our planet, our buildings and the well-being of those who inhabit them.

Seniors’ Evolving Tastes

When it comes to dining, seniors’ tastes are evolving, which is impacting how senior living communities plan and design food and beverage amenities.

In a Q&A with Environments for Aging, Darla Esnard, Principal and Co-Director of Senior Communities, discussed the increased importance of designing senior living facilities to incorporate flexible food and beverage spaces, balancing accessibility and aesthetics, and design elements that promote socialization.

Q: How are seniors’ dining expectations changing?

We are continuing to see the shift toward restaurant-style dining with a varied atmosphere. Gone are the days of one large formal dining room—today’s seniors want variety and choice in both their dining venues and types of cuisine. Most communities we are working in today, whether it be a renovation, repositioning project, or a new ground-up project, are asking for multiple dining experiences for their residents.

Aegis Living Bellevue Overlake

Q: What’s driving this?

A few factors. Seniors are used to having dining and restaurant variety at their fingertips. Not only can they get it from restaurants, but it is also available online and via delivery. They expect this same quality and experience in senior communities.

Additionally, more people are aware of the important role food has on our overall health. Seniors are seeking food personalized for their nutritional needs. They are demanding fresh, nutritional food that promotes longer, healthier lives.

Q: What design considerations can support flexible dining spaces that are also efficient for communities to operate?

It’s important to create flexible dining spaces that can transition throughout the day. For example, a café space that is used for breakfast or coffee in the morning can transition to a social bar space at night. A larger dining venue can have hidden screens and AV equipment to allow the larger space to be used for meetings or special events when not serving meals.

Lastly, carefully planning the location of your main kitchen and keeping it directly adjacent to all dining venues and/or a direct elevator ride to another dining venue saves money on repetitive equipment and also keeps staff co-located in a central area instead of spread over a larger community.

Aegis Living Laurelhurst

Q: What’s on your list of must-have features for senior dining environments today?

Seniors need to be comfortable in their dining experience or they won’t want to linger and be social with other residents. The atmosphere must have excellent lighting–lots of natural light without glare. Noise in dining rooms is one of the biggest complaints we hear from residents. Utilizing good sound dampening materials is crucial in reducing noise and giving a resident a comfortable experience. A dining room that’s easily maneuvered is critical as well as the dining chair. It must be designed with the senior in mind and easy to get in and out of, with good support and comfort.

URC Dining Renovation

How to Adapt Aging Office Spaces for a Modern Workforce

Office leasing trends are shifting and many tenants are favoring new developments, posing significant challenges for older office buildings in maintaining occupancy. As tenants seek out flexible, wellness-focused, and tech-enabled work environments, owners of these aging office buildings must rethink their strategies to attract and retain occupants.

With the right approach, there is significant potential for older office buildings to thrive. By embracing targeted upgrades and creative design interventions, building owners can reposition these assets to meet the needs of modern tenants while creating unique competitive advantages in the marketplace.

As architects and designers, we play a crucial role in reimagining outdated spaces and breathing new life into these properties.

Leveraging innovative strategies based on a deep understanding of current workplace trends, we can transform aging office buildings into future-ready environments that align with today’s focus on flexibility, technology and wellness.

Creating Flexibility and Opportunities for Personalization

One key design strategy to enhance the competitiveness of aging office buildings is incorporating flexible layouts and personalized settings.

In today’s hybrid work environment, employees are looking for a workplace that can accommodate various work styles and preferences — whether it be quiet zones for focused work, collaborative areas for team meetings, or lounge areas for informal discussions.

To meet these diverse needs, it’s important that we create adaptable environments that promote versatility and productivity, ensuring that every employee can find the right setting for their work.

Open floor plans, modular furniture and multi-purpose spaces are essential components of this adaptable design approach. These plans offer flexibility through their reconfiguration ability, encourage communication and collaboration through the removal of physical barriers and enable diverse work zones to meet evolving employee needs.

Modular furniture complements this layout and facilitates effortless rearrangement and customization. Pieces such as adjustable desks, stackable chairs and movable partitions empower organizations to create tailored environments — whether for brainstorming sessions, team meetings or individual focus time.

Community Transit Merrill Creek

Multi-purpose spaces, designed for versatility, also enhance flexibility, enabling areas to be quickly transformed for various needs. For instance, a conference room that typically serves as a meeting space can be easily converted into an event venue with retractable walls. Implementing these design elements provides leaseholders and employees with the ability to modify their workspaces as needed.

While flexibility lays the groundwork for dynamic workspaces, personalization plays a vital role in enhancing employee satisfaction and productivity in the workplace. Allowing individuals to tailor their workspace empowers employees to create environments that align with their unique needs.

Incorporating elements like adjustable lighting, climate control, and ergonomic furniture allows employees to craft their ideal settings, fostering a sense of ownership that inspires engagement and fuels creativity.

Amenity Spaces: Wellness and Sustainability

Modern occupants are no longer satisfied with offices that simply provide a desk and chair — they’re seeking spaces that enhance their well-being and align with their values, especially when it comes to wellness and environmentally friendly practices.

For aging office buildings, this shift presents both a challenge and an opportunity. To remain relevant, these buildings need to incorporate wellness-oriented amenity spaces that promote sustainability, giving them a renewed sense of purpose and appeal.

To truly capitalize on this opportunity, we must offer a comprehensive suite of wellness features that enable older buildings to stand out in a competitive market. Thoughtfully designed amenities like fitness centers, meditation rooms and outdoor spaces give employees places to recharge and refocus throughout the day.

Coupling these wellness-driven spaces with sustainable initiatives — such as energy-efficient systems, water conservation measures, and the use of healthy materials — further elevates the appeal in attracting companies prioritizing health and wellness, and sustainability.

Community Transit Merrill Creek

This approach was realized in the redesign of Community Transit Merrill Creek in Everett, Washington, where we embraced a holistic approach to the interiors, transforming the space into a sustainable, hospitality-driven amenity center for both transit drivers and administrative employees.

The finished project included health-conscious amenities like a wellness area offering massages and chiropractic care, as well as a fitness center complete with workout machines, free weights, and a dedicated yoga space. We also added two stories of both relaxing, low-energy comforts and active, engaging amenities providing employees with a space to read, relax, and rest in the sleep and quiet rooms or play pool and watch TV in the social break room between shifts.

Technology and Smart Building Solutions

Design and technology are inseparable, and incorporating smart building solutions is no longer just a trend — it’s essential to meet the demands of modern occupants and future-proof office environments. Smart systems such as touchless entry, IoT-enabled sensors for space utilization, and AI-driven building management systems help create spaces that respond intuitively to the people who use them, ensuring a seamless blend of innovation, efficiency and user experience.

Integrating smart building systems that automate essential functions like lighting, heating, cooling and security can significantly reduce energy consumption and also offer occupants greater convenience and control.

These systems are designed to optimize building performance, adjusting energy use in real-time based on occupancy, weather conditions or time of day. The result is not only a more sustainable operation but also yields substantial cost savings. Advanced Building Management Systems (BMS) take this a step further, automating routine operations and delivering valuable analytics that improve maintenance and extend the lifespan of the building’s infrastructure.

Community Transit Merrill Creek

Future-Proofing Workplaces: Designing for Flexibility, Wellness, and Sustainability

To remain competitive, the key for aging office buildings lies in making strategic design choices that emphasize flexibility, wellness, sustainability and technology. With the incorporation of adaptable layouts, wellness-centered amenities, and smart building systems, these properties can be better equipped to cater to evolving demands for dynamic, health-conscious work environments.

As designers, we play a crucial role in reimagining these spaces, transforming them into future-ready workplaces that foster both well-being and productivity while preserving noteworthy original architectural character. Through thoughtful design interventions, aging office buildings can not only stay relevant but also thrive as innovative and sustainable solutions in today’s real estate landscape.