There are many unique buildings located along the West Coast. Built in the 1920s and 30s but now vying for a second chance at life, an existing turn-of-the-century warehouse in Seattle is one of them. After having been identified as a prime candidate for an adaptive reuse conversion, the former warehouse is being repositioned as a mid-rise apartment complex.

Leveraging the unique elements from the site’s previous use, adaptive reuse conversions aim to accomplish goals identified by the project’s owner. In this case, maximizing the yield and resident experience, and including amenities that attract and enhance resident life.

This is something that Ankrom Moisan has unique experience in; We embraced adaptive reuse to resurrect downtown Portland’s Pearl District, turning disused warehouses into coveted apartments.

Chown Pella Lofts, a disused factory warehouse that was converted to a multi-story residential condominium in Portland’s Pearl District.

Here’s how we do it:

Maximizing Yield and Resident Experience

Converting an old warehouse into an apartment building with modern luxuries means embracing the elements that made the structure a warehouse in the first place. Finding the design elements that are inherently aged and providing them with a new use is just one way to maximize the building yield, as well as the resident experience.

For example, warehouses typically have floor-to-floor heights that can reach 15 feet, something that’s not commonly found in contemporary housing. The additional space afforded by such heights allows for deeper floorplates and units than modern constructions, up to 120 feet wide, allowing the building to utilize the extra space afforded by the deeper floorplate to enable larger, light-filled units – something residential buildings typically don’t have.

Similarly, older warehouses that did not utilize electricity to the extent that modern buildings do have large windows with lots of glass to bring an abundance of natural light into the space. With an adaptive reuse conversion, what was one intended to bring daylight to hard-working warehouse laborers can be repositioned to provide residents with sweeping views of their surroundings.

Amenities that Attract and Enhance Resident Life

Comparing the resident experience found in an adaptive reuse project to that of modern housing, it’s plain to see that the bespoke qualities of a conversion add richness to a space. Unusual features become draws for potential residents, just as long-empty warehouses are converted into bedrooms and apartments full of life.

It all has to do with spotlighting a structure and emphasizing quirks rather than designing them out.

For this project, we saw the warehouse’s skeleton as an opportunity to create one-of-a-kind amenities that cannot be replicated in a new build. Turning the light well atrium into an internal amenity space, complete with a spa and garden, our design emphasizes resident wellness and provide a peaceful retreat from the city and the urban, hard-edged waterfront found nearby – something you won’t find next door.

Successful adaptive reuse conversions embrace the factors that make their buildings different, using those differentiators to become more desirable in the market. It’s our view that the unique history, location, and geometry of projects like the existing turn-of-the-century warehouse lends itself to the creation of amenities, and apartments, that surprise and delight residents.

Overall, warehouse to residential apartment adaptive reuse conversions are unique exactly because they’re not a unique situation. Older, underutilized, turn-of-the-century warehouses in a downtown core are a very common building typology that exists all across the West Coast. They usually have between five and seven stories, and massive footprints that are a lot larger than what would be expected to be adapted to marketable housing.

Chown Pella Lofts

The unique charm of these conversions comes from how you take a building and use the features that exist because it was designed to meet warehouse code at the time (of construction) to make impactful housing.

Buildings like these are often already landmarks in the cities they’re located in, being 100 years old, sometimes older. The question is, how do you reintroduce a historic landmark after it’s been given a new use? Embracing the existing exterior architecture to retain the site’s identity while adding new features to set it apart from the past will get people into your building.

This could be done by turning an old water tower into an art installation to act as a beacon and attract attention, for example. In most cases, it’s very exciting for passersby to notice an old building in a new light. If you can do this, your adaptive reuse conversion will continue to be a part of the fabric of the city that it’s in, revitalized and full of new life.

Relationships are the Cornerstone of Designing Successful Public Projects

Unlike private development, public agency projects often require more time and thoughtful steps at the outset. It’s not that private projects skip these entirely, but the stakes are different: public projects are deeply tied to community trust, transparency, and long-term public value.

Over the years, we’ve found that a strong foundation makes all the difference. Here are three key focus areas we emphasize at the start of any public agency partnership – setting the tone for a collaborative, lasting relationship:

-Establishing Design Expectations & Building Trust

-Defining Guiding Principles

-Engaging the Community Early and Often

Design Expectations = Trust in Action

When kicking off a public agency project, one of the most valuable things you can do is establish trust early – between the ownership team and the design team. That trust starts with clarity around how the design process will unfold, including what’s expected in meetings, how feedback will be gathered, and when key decisions will be made.

A powerful tool in those early conversations? Precedent imagery.

Images of outdoor spaces, interior environments, furniture, building materials, and comparable projects for interiors and exteriors, can help teams express what resonates with them – and just as importantly, what doesn’t. These visual references spark honest conversations and surface values, priorities, and design preferences that might otherwise stay unspoken.

When teams feel comfortable telling us as designers “this doesn’t quite feel like us,” you know you’ve created the kind of collaborative environment where good design thrives.

Harnessing Stakeholder Input: Turning Insights into Actionable Guiding Principles

When our client invited over 800 employees to share their perspectives on project goals and values, it created a powerful opportunity – and a complex challenge:

How do you distill so many voices into a clear, actionable executive summary?

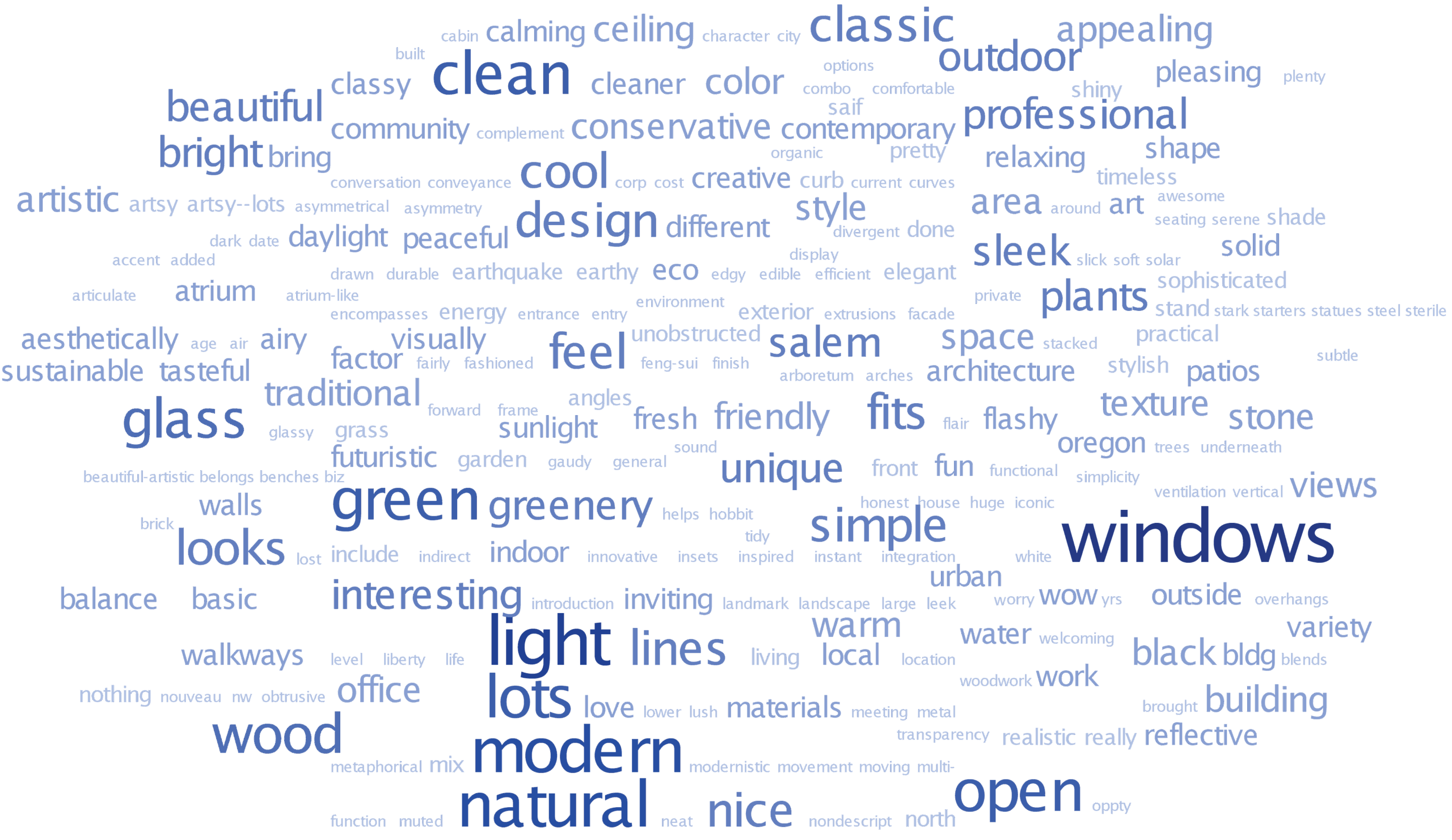

One highly effective method we recommend is the use of a word cloud.

By capturing the most frequently mentioned words and ideas, a word cloud surfaces the priorities that matter most to stakeholders. These guiding principles become a foundation for decision-making, aligning the owner, designer, and construction teams around a common vision.

In our experience, tools like word clouds are critical in early project stages. They translate complex input into focused design drivers, ensuring that stakeholder values are not just heard – they are built into the fabric of the project itself.

Survey responses, interviews, and meeting discussions all offer valuable language that can be mined to create clarity, consensus, and momentum. For SAIF, we started out with this world cloud, and this is how we ended up!

Saif Headquarters

Community Voices: Designing and Inclusive Engagement Process

When working on publicly-funded projects, one thing is always true: you’re not just designing for a client – you’re designing for a community. That comes with both opportunity and responsibility.

Community engagement isn’t just a box to check. It’s a chance to build trust, reflect diverse needs, and ensure public dollars are spent in a way that truly benefits the people who live, work, and move through the community.

But engagement looks different for every client and every community. Some just need you to listen. Others want to inform after the first session or collaborate across several touchpoint. The key is meeting people where they are and providing tools that support informed dialogue.

What should you be prepared to provide the public?

-A clear project overview in everyday language (and possibly in multiple languages)

-Visuals or diagrams that communicate design intent

-A summary of what decisions have been made vs. what’s still open for input

-A way for people to respond – whether it’s in person, online, or through community partners

We’ve learned that when you design the process with care, you end up with stronger outcomes – and stronger relationships.

Celebrating Our Female Leaders

First kicked off in 2024, the AMasterClass series is an ongoing discussion dedicated to celebrating and sharing the knowledge, insight, and advice accumulated by the female leaders at our firm over the years. They are five-minute-long, miniature crash courses on valuable lessons learned throughout their careers, told in the format of a MasterClass lecture discussion.

An introduction to 2025’s AMasterClass, A Celebration of Female Leaders, shared by Stephanie Hollar.

This year, the three women who opened up to share their experiences with the rest of the firm were Bethanne Mikkelsen, Senior Principal and Office/Retail/Community Studio Co-Leader, Rachel Fazio, Vice President of People, and Alissa Brandt, Vice President of Interiors.

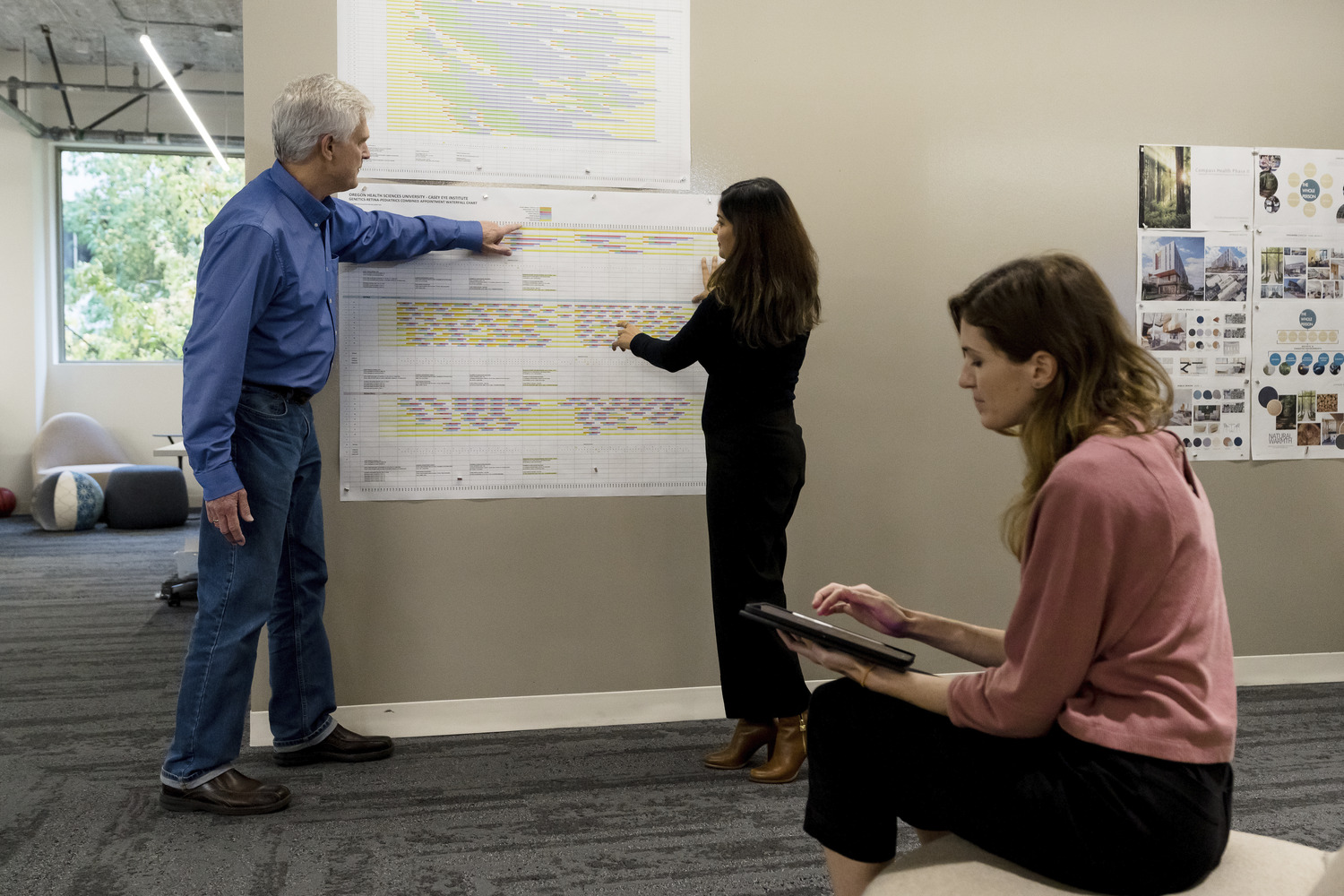

Bethanne, Alissa, and Rachel take part in the live AMasterClass panel in Ankrom Moisan’s Portland office.

Hosted and moderated by Sheana Hawes, HR Generalist, the three female thought leaders conducted a panel discussion in Ankrom Moisan’s Portland office, sharing their insights, knowledge, and experiences with a live audience, and discussing the similarities between the challenges they face and the lessons they’ve learned from overcoming those challenges.

The graphic from 2025’s AMasterClass event.

Bethanne discussed what it means to be an empathetic leader, sharing that “utilizing these techniques improves team collaboration, increases employee engagement, and enhances communication.”

Rachel shared her perspective on resilient leadership, declaring “you have to build the right mindset for leadership, lead with positivity and humor, and focus on solutions rather than the problem.”

Alissa enlightened us on design-forward leadership, reminding us that inspiration isn’t static – “take time to reflect on what drives you now versus what motivated you at the beginning,” she said. “Let inspiration evolve with your experiences.”

The wisdom shared by Bethanne, Rachel, and Alissa this year – as well as last year’s speakers’ thoughts on Harnessing Your Voice, Being Your Authentic Self, and Solving the Unsolvable – can be viewed in the playlist below.

A playlist of discussions from 2024 and 2025’s AMasterClass series.

Michael Stueve’s Workplace Design Trend Predictions for 2025

Co-leading Ankrom Moisan’s workplace interiors team for over half a decade, Michael Stueve, Principal, knows the ins and outs of workplace design like the back of his hand. His experience with Futures Thinking has prepared him to identify many office trends before they spike in popularity and become a regular design consideration, like hybrid work capabilities and the importance of fortifying culture through the built environment of an office space.

Reflecting on recent project work, Michael has pulled together and shared his top workplace design trend predictions for 2025.

“Although COVID-19 ushered in a reimagined workplace experience over the last few years, one truth remains unchanged,” Michael shared. “That is that successful businesses excel at aligning physical office spaces with organizational values and emerging work practices.”

Michael Stueve, Principal

“Collaboration and amenity spaces have certainly been upgraded over the past few years, but what’s next?” Michael asks. As workplaces are ever evolving, he sees three significant drivers for 2025’s evolution: AI, fresh air, and inclusivity.

AI

“As AI is dramatically impacting the way we work and redefining job roles, businesses will require ever more enhanced collaboration areas that double as training and up skilling hubs,” Michael predicts. “These spaces will feature cutting-edge integrated technologies, flexible furniture, sophisticated audio systems, and designated presentation zones.”

Merrill Creek | Everett, WA

“This evolution signifies a blend of workplace and higher education design strategies, fostering continuous learning and adaptability,” he said.

Fresh Air

“From a wellness perspective, our client surveys reveal that the number one amenity employees are seeking is not pickle ball. It’s fresh air and daylight,” Michael said.

“For instance, we recently had a client in a Class-A CBD office tower relocate to a floor with a large private outdoor area connected to the break room,” said Michael, speaking of the recent Colliers PDX Headquarters project. “The result is that team members coming to the office daily have increased by 50%. Couple this with biophilic elements and natural materials, and you’re set for the coming year and beyond.”

Colliers | Portland, OR

Inclusivity

On top of rapidly changing technologies and connections to nature, there are other opportunities Michael has identified as workplace design trends this year. One of these is designing spaces that support a journey to belonging through inclusive interiors elements.

All-gender restrooms, quiet zones for neurodiverse employees, and improved accessibility for individuals of all capabilities all contribute to an inclusive office atmosphere, signifying that a company truly carers about its employees and is willing to address their needs in meaningful, impactful ways.

Amberglen, a recent office project outside of Portland’s downtown core merges the fresh air trend with an inclusive atmosphere. “The owners had the opportunity to amenitize the space to the level of a downtown Class A, capitalizing upon an indoor-outdoor opportunity for tenants,” Michael said. “With an eye towards wellness, inclusivity, and fresh thinking, Amberglen includes elements that bring the outdoors in, as well as spaces that encourage tenants to bring work outside. Having outdoor work areas means there is cross-pollination between the two approaches to wellness and inclusivity.”

Amberglen | Hillsboro, OR

Although these amenities and considerations have been done before and are nothing groundbreaking on their own, joining them together creates new experiences and perspectives for office tenants, re-framing the everyday impact of emerging technologies like AI and the importance of biophilia.

“When you combine the elevated collaboration that stems from technology with fresh air and inclusivity, they all total up to wellness,” Michael states. “When all three things are firing on all cylinders, it creates an environment of wellness, which is the greatest amenity of all.”

Things Your Architect Wishes You Had Done in Masterplanning

In architecture and urban planning, masterplans are strategic documents that design, organize, and plan for the development of a large site or area containing multiple blocks or buildings. They provide a comprehensive framework for the development of an area of land to be used, whether it is for housing or other building types, infrastructure, or open spaces for a community or certain property. They establish the overall vision for a property that allows for coordinated decision-making as individual building or infrastructure projects are designed and implemented over time.

Ankrom Moisan has worked on many buildings within larger masterplans throughout California’s Bay Area as part of Special Use Districts or Specific Plan Updates. We enjoy working on these projects since they have the potential to make a tremendous positive impact on the area where they are constructed, which is exciting. Masterplan projects can create thriving new neighborhoods or contribute to a massive infusion of jobs, housing, and community amenities that reinvigorate existing – yet stagnant, historically under-invested, or under-resourced – neighborhoods. One of our recently completed projects, The George, a 20-story high-rise in San Francisco, was completed as part of the Fifth and Mission Special Use District which had that exact intention.

An aerial shot of The George and the surrounding Fifth and Mission Special Use District

Risks

Of course, while there is a great possibility for a large, impactful success with expansive projects like these, masterplans also come with a lot of risk for the developers that back them. Often, the biggest risk taken by developers in our environment of rapidly shifting construction and real estate markets is timing. These masterplans are for projects that can take many years, maybe even a decade, between the start of the planning process and a building’s completion, so every early decision really counts.

A thoughtless decision in the initial layout of a lot or in the design parameters that get baked into an EIR* can very easily balloon a project’s timeline. If an individual building’s design is consistent with the design guidelines studied in the masterplan’s EIR, then the building doesn’t need its own separate EIR. However, if a project deviates from what was studied in a masterplan’s EIR, there’s a chance that the building will need to conduct its own environmental review, which is a very long process. This can spiral out of control when every building needs a time-consuming modification to rectify the issue. On the other hand, well thought-out initial design documents can facilitate a smooth entitlements process, meaning that you get exactly what you expect on your project while shaving months or years off the approvals timeline, directly resulting in earlier TCOs**.

How Architects Can Help

As architects we’ve worked on complex projects like this with many development partners. We know what strategies work well and what common pitfalls to avoid. We want to ensure that complex masterplans are not more complex than they need to be.

Video: Navigating Complex Entitlements with Architect Chris Gebhardt

Working hand-in-hand with architects throughout the process to design buildings as guidelines are being developed is the best-case scenario for masterplans with complex entitlements. Your priorities become the driving force when the building designs are actively influencing the design guidelines, instead of merely reacting to them. It’s so much easier to make the case that a massing modulation requirement is overly restrictive by showing the city a beautiful non-complying building they would be happy to approve before that compliance language gets codified than after, when they and you are forced into a time-consuming mediation process. In some cases, owners have been able to use excerpts from our SD design packages as the actual “design guidelines” so they know they’re going to be allowed to build the building they want and allowing them to skip the whole process of developing generic design guidelines that could backfire. In this scenario, when the individual buildings need to be entitled its basically a rubber stamp review.

Even if the architects can’t be brought on for a whole initial design phase it can still be impactful to get them on board for occasional test fit checks, studying the lots and design standards you are considering implementing. It does not require consistent work (with associated consistent fee burn) but can be done as short studies here and there, and if you’re using the same team, they can get increasingly efficient with the studies and then translate what they’ve learned into an efficient early design phase once you get to that point. Our tier 2 feasibility study service provides a quick-yet-accurate understanding of the yield potential of a site. Typically, it includes a full zoning analysis, a zoning mass impacts table, buildable volume diagrams, and graphic site location and zoning, among other expected deliverables like simple floor area plans, an area summary, and simple massing diagrams. In the context of developing a masterplan, this template can easily be used to study the impacts of design requirements.

While it’s ideal for an architect to get involved with a project in the early planning stages, bringing on an architect at any stage means that you’ll get an expert’s input on integral elements such as lot dimensions, building heights, fire access, and building utilities.

For The George, part of the significant 5M development in a historic part of San Francisco, we were unable to join the project early on, meaning that we had to rely on other solutions to streamline the entitlements process and make the project more efficient in terms of both time and money. To create this 20-story high-rise (one of the largest housing developments in San Francisco), we implemented a combination of different strategies for navigating complex entitlements for large masterplans, resulting in a final structure that was practical and passed entitlements reviews while also still being beautiful and transcendent.

Here is a glimpse of some of the insights that might be shared by an architect who is brought into a project at a later stage, that can still help avoid the complications and delays that are commonly associated with complex entitlements and masterplans.

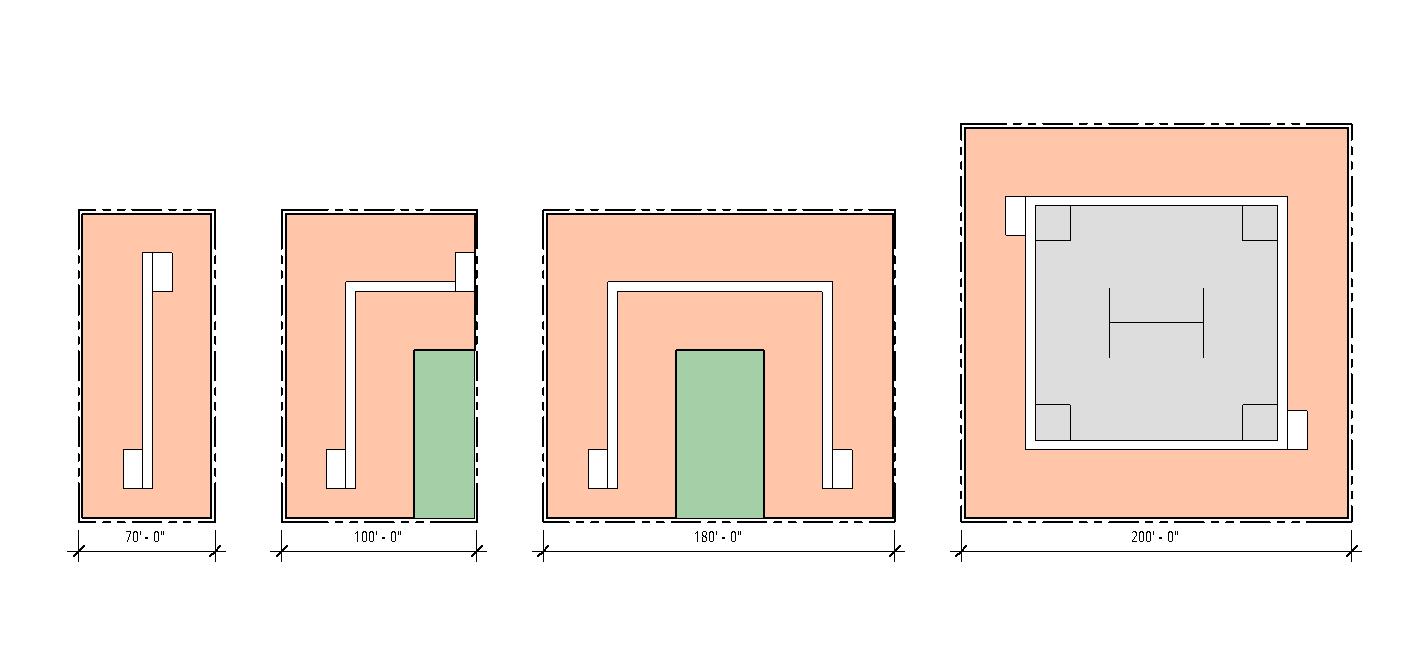

1. Lot Dimensions

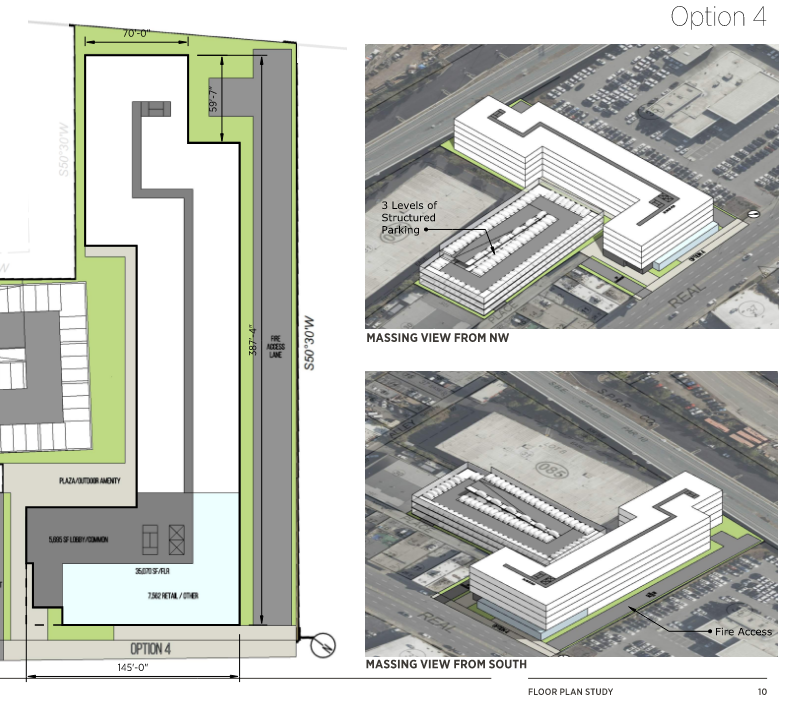

There are modules that work efficiently for different buildings and building types. In mid-rise construction, an efficient double-loaded corridor building wing is about 65 to 70 feet wide, so site dimensions smaller than that can be a serious challenge for multifamily developments. If you need on-site open space or daylighting, then that requires another 30 or 40 feet, which means you want at least 100 feet for an L-shaped building. If you want a full U-shaped building, then you’ll need 180 to 200 feet with exposure on at least three sides. For a parking wrap or “Texas Donut” style building, you’d need at least 200 feet minimum.

Minimum efficient lot dimensions

Lots with dimensions that fall between these sweet spots often lead to inefficient building layouts, such as single-loaded corridors, or they aren’t able to utilize as much of the site for rentable units as would be preferred.

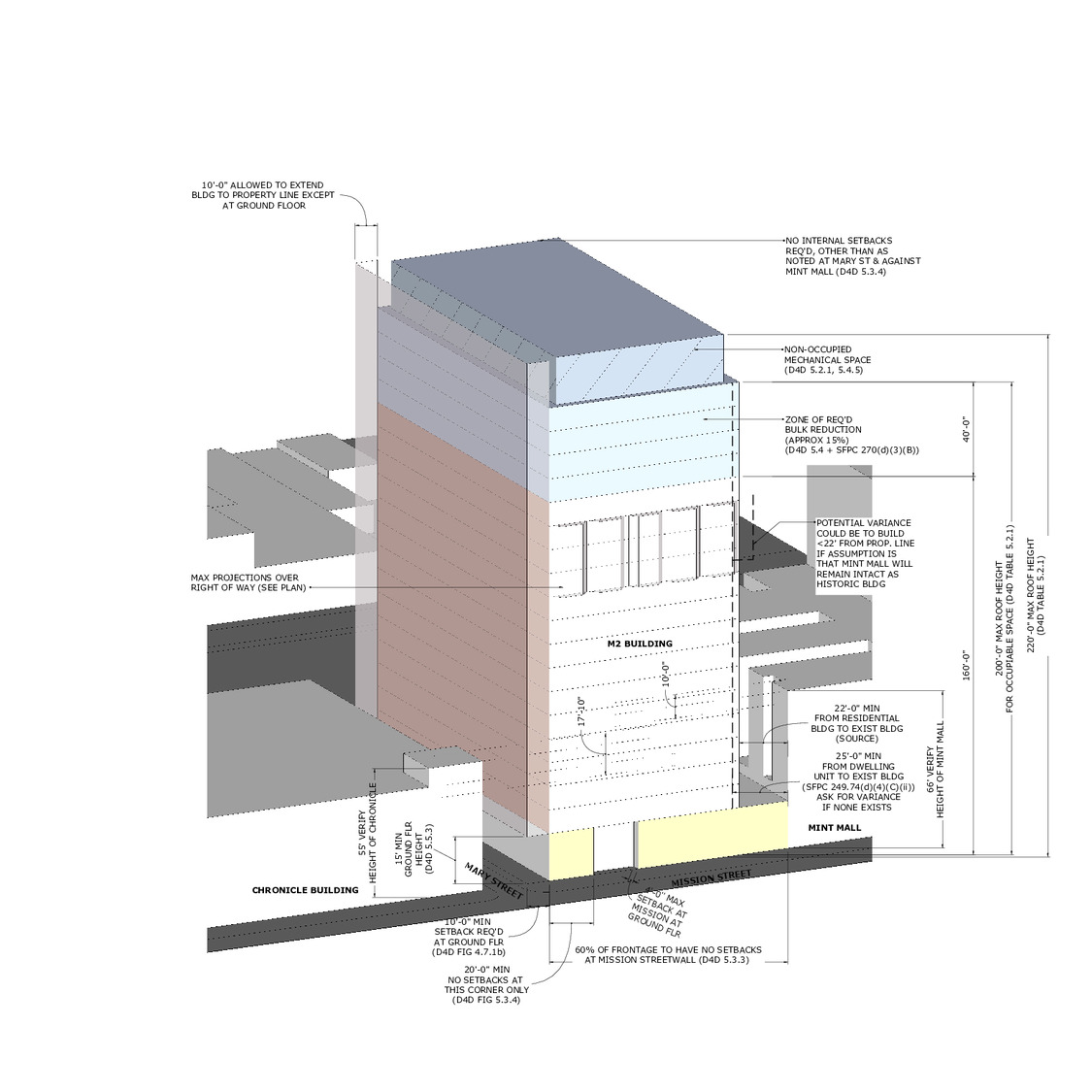

2. Building Heights

Building height limits tend to be set in increments of five or ten feet, which isn’t an issue if you can keep in mind that real building heights are a bit messier than that. It’s rare. for a residential floor to actually be 10 feet high. 10′-6″ is a much more comfortable floor-to-floor height for wood-frame housing than 10′-0″ is. If there are ground-floor residential units, it’s likely that they will be raised above the sidewalk, meaning that a couple of feet need to be added to the height to account for that step-up into the building. Another couple of feet need to be added for the roof, as well, since it’s always thicker than a typical floor.

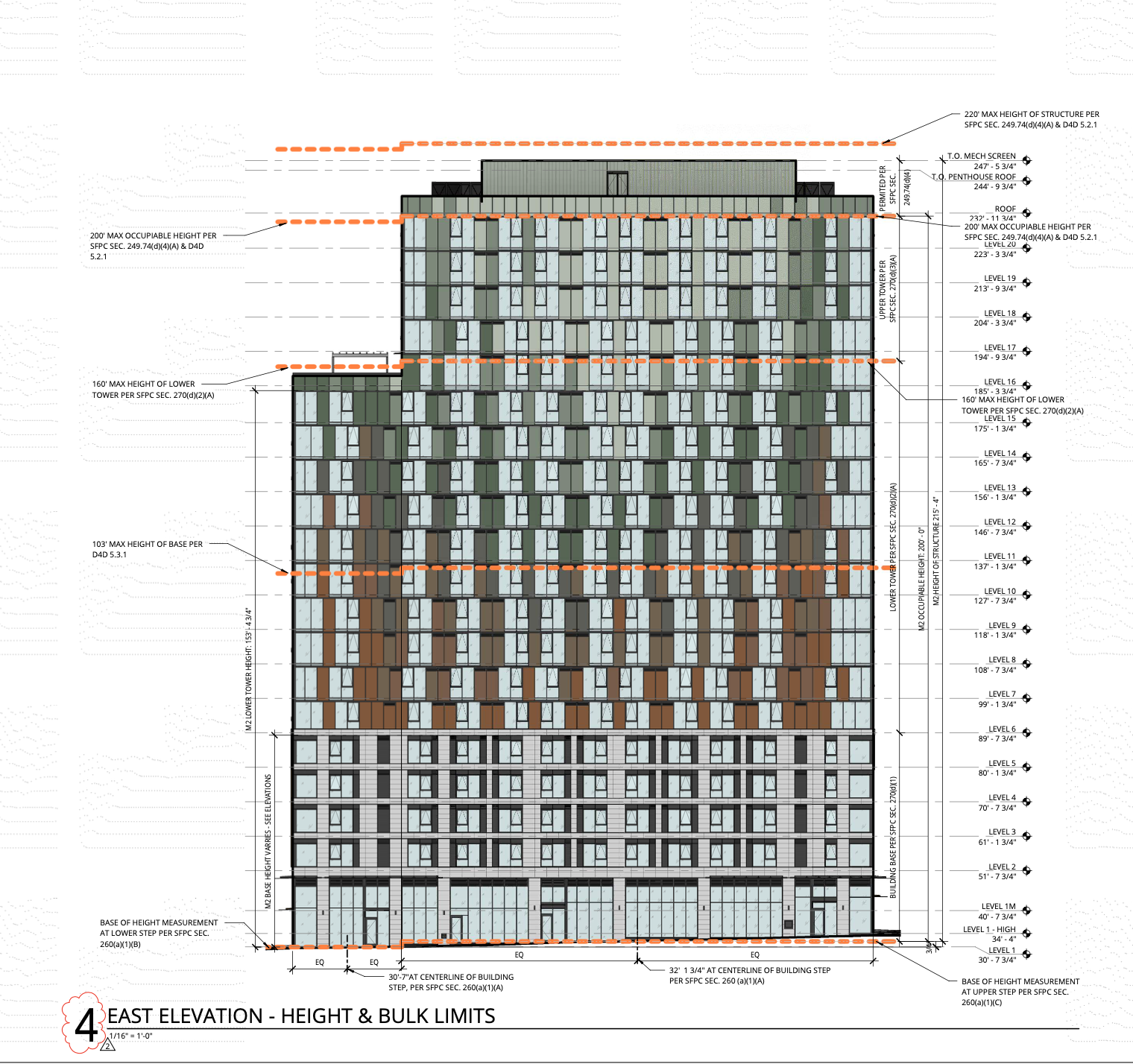

Preliminary height & bulk requirements analysis for The George’s site

While thinking about the height you want for your building, be sure to check where your jurisdiction measures the top of the building to, as some will measure to the parapet while others measure to the roof surface. You’ll need to check if elevator penthouses can be excluded, and how they address sloped sites, among other things. These nuances can really make or break the yield on a site, so it’s worth spending a little extra time thinking about the limitations of a height limit and checking all the edge cases to ensure that you can get what you want on your site.

Height limit compliance diagram for The George

It’s also important not to forget that building code limits low-rise construction to 75 feet from the lowest level of fire department access to the highest occupied floor. Anything above that falls into the more expensive high-rise territory. These heights can also influence the types of material used during construction – wood can be utilized for buildings under 75 feet, while anything above that height needs to use concrete or steel.

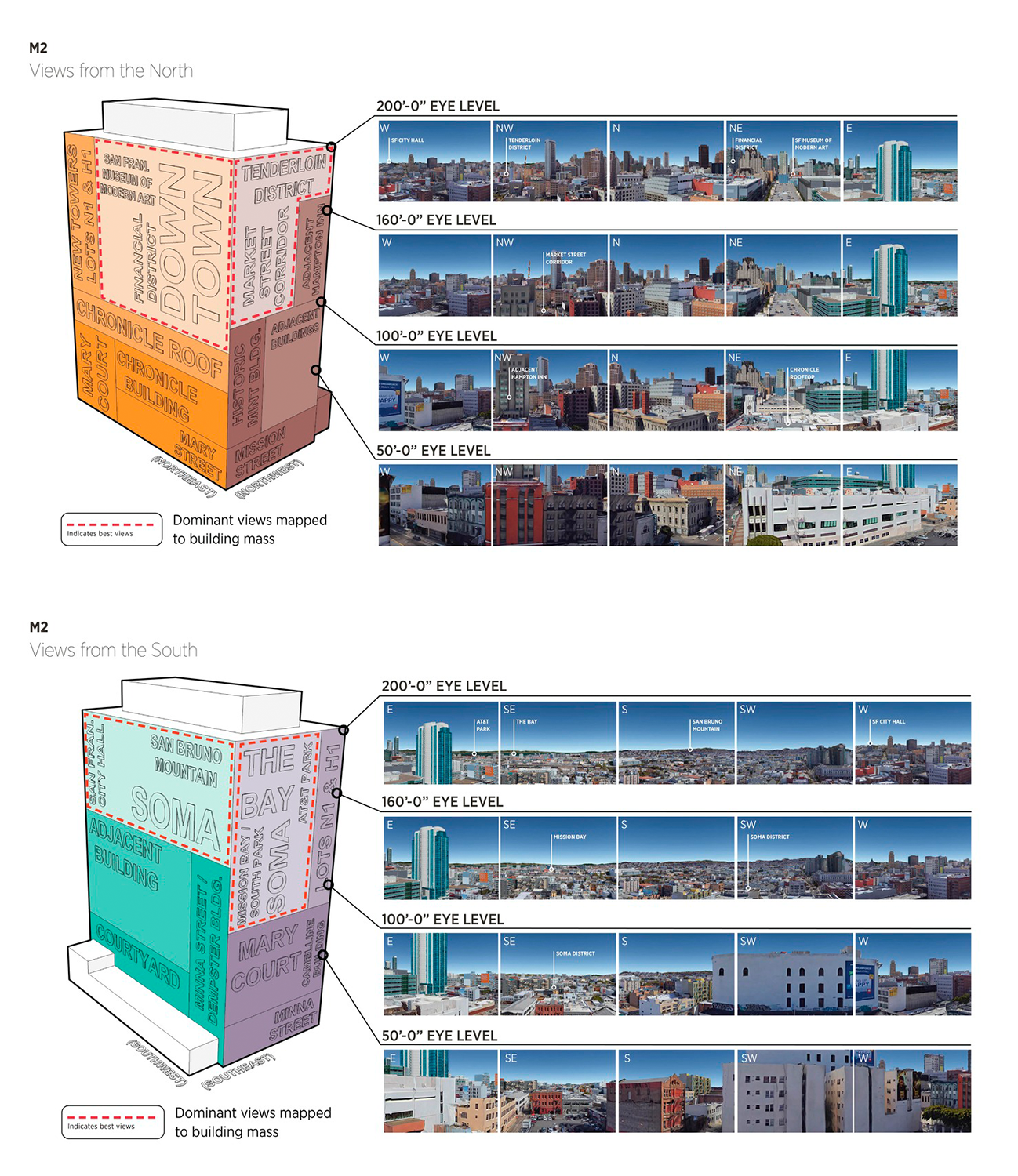

View analyses at various heights for The George

3. Fire Access

Building code states that firetrucks must be able to get close to a building, meaning that any solid masterplan needs to account for a fire access road along one or two sides of the structure. One of the real luxuries of laying out both the lots and the adjacent roads for a project is that you can make sure that fire access works from the very beginning. There’s nothing that wipes out a site’s capacity faster than needing to run a 26-foot-wide aerial apparatus access road through it – if fire roads aren’t accounted for, it will impact the size and shape of your building.

A yield study for a different project that didn’t end up penciling out due to the fire access lane that ended up being necessary

The best way to avoid this is to coordinate with local fire authorities to ensure that they have adequate access to each site. This usually means providing a 26-foot clear road along one complete side of the building, located between 15 and 30 feet from the face of the structure. With that provided, it’s a good idea to make sure that there is a point on the lot perimeter that’s within a 150-foot path from a minimum 20-foot wide apparatus access road. Easy fire access will really open up a site and increate the ability to optimize building shape for yield and efficiency, rather than fire compliance.

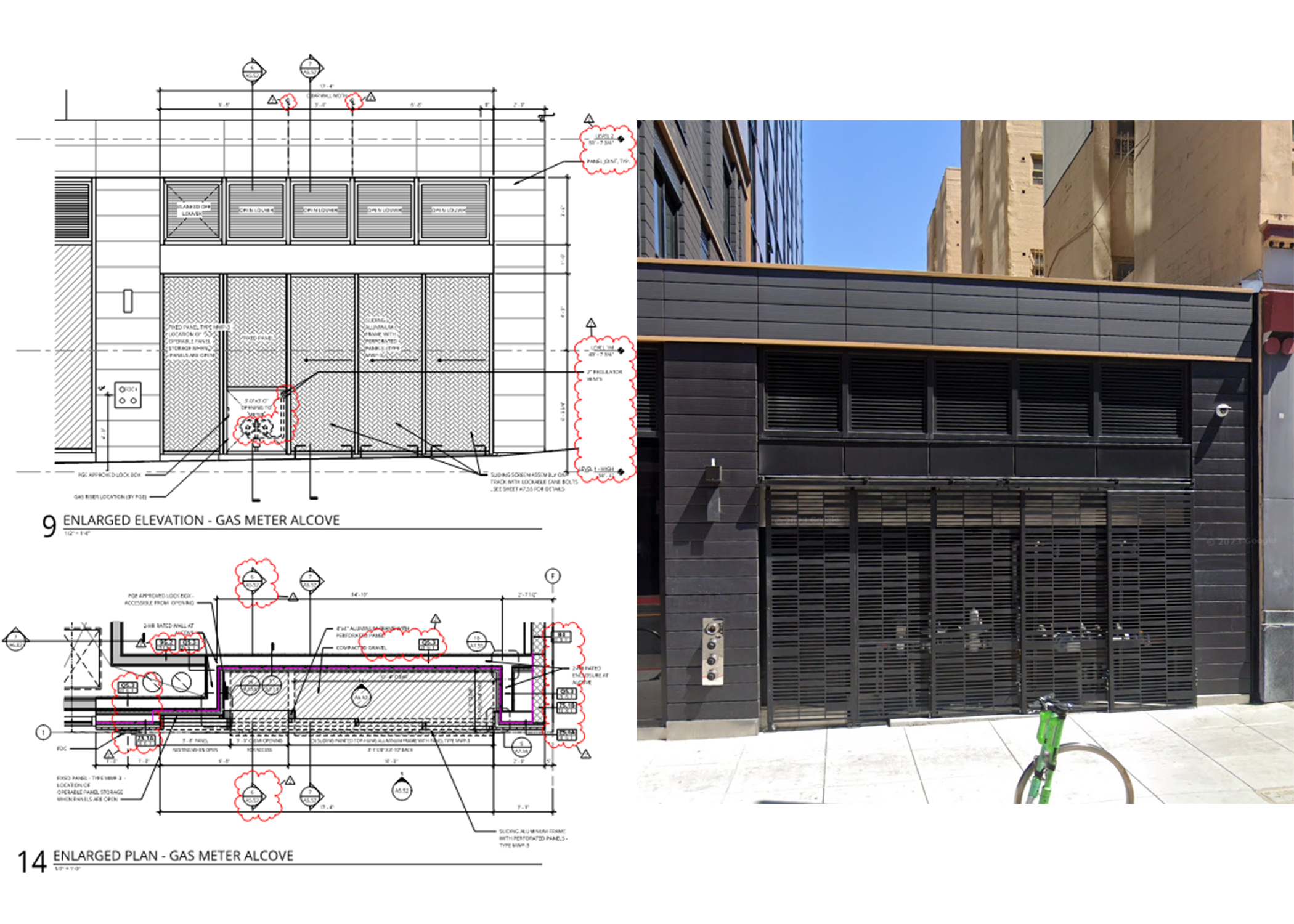

4. Building Backs / Utilities

These days, utilities in California are becoming more and more demanding about getting dedicated spaces on the perimeter of buildings, while planning departments are becoming less and less permissive about allowing those dead spaces to eat up active pedestrian frontages. Creating a hierarchy of streets in your masterplan that includes de-emphasized service roads or alleys is the best way to give each regulatory agency what they want while also providing an easy place to locate all the unattractive but necessary functions like loading docks, transformers, and other utility rooms where they won’t spoil the primary frontages you’re using to create pedestrian environments that appeal to both residential and retail tenants. Placing utility infrastructure like gas alcoves, water entry points, and other industrial rooms in locations that are not prominent in the design of a space is one solution that allows for the inclusion of these necessary considerations while allowing them to be de-emphasized. Though we do our best to incorporate these significant spaces into the overall designs of buildings, it is easier and much more cost effective to ‘hide’ them when there is a backside to the building that will not be visible to the public.

The gas meter alcove at The George

Conclusion

Though translating necessary design considerations resulting from code into something that is both practical and beautiful can be extremely challenging if you don’t get a head start with coordinating all the aspects of a project, by adhering to these tips for designing winning masterplans and considering architectural components of a building earlier in a project’s lifecycle, the overall process of working on complex masterplan projects can be streamlines and made more efficient.

*EIRs, or Environmental Impact Reports, are multi-year studies done for any big project to comply with California’s Environmental Quality Act.

**TCOs in this context are Temporary Certificates of Occupancy. They’re the first permits that allow tenants to occupy units and building owners to collect rent. It marks the transition from a building being a “construction site” to becoming a site that anyone can go inside and use. Acquiring this certificate early translates to being able to open your project up to the public and collect revenue, sooner.

Six Lessons Inspired by 2024 DJC Women of Vision Honoree Mariah Kiersey

Held annually, the Daily Journal of Commerce (DJC) Women of Vision award recognizes and honors women who are shaping the built environment with their technical skill, leadership, mentoring, community involvement, and creation of opportunities for future generations of women in the industries.

Nominated by her peers, Senior Principal and Office/Retail/Community Studio Co-Leader Mariah Kiersey was selected by the DJC as an honoree for her contributions to Ankrom Moisan and the greater Portland community.

Mariah Kiersey celebrates her recognition as a Woman of Vision in Ankrom Moisan’s Portland office.

The epitome of a strong female leader, Mariah consistently demonstrates exceptional leadership, creativity, and dedication to both her craft and team. According to Murray Jenkins, Vice President of Architecture, “her ability to inspire and guide her team has significantly contributed to our firm’s success and reputation in the industry. She consistently demonstrates a commitment to excellence and a passion for mentoring others.”

However, Mariah’s contributions to our firm extend beyond her role as Co-Leader of the Office/Retail/Community studio; she is a trusted colleague and an inspiring leader who fosters an environment of innovation and inclusivity.

Within Ankrom Moisan, Mariah is “one of those rare architects who have an incredible amount of grit,” said Dave Heater, President. “This shows up in how hard she works and how much she cares about doing great work for her clients and helping those on her team learn and grow.”

One of her many contributions to the firm in this sense are the lessons she imparts – knowingly or unknowingly – to the rest of the firm. Here are six lessons on how to be an employee of vision, inspired by Mariah and her award-winning work ethic.

1. Get Involved

Mariah is a passionate advocate for community health, often volunteering her time and expertise to support local initiatives aimed at providing essential services to individuals facing mental health challenges. Her work in designing and developing behavioral health facilities reflects her deep understanding of the critical role that well-designed spaces play in supporting mental health and wellbeing.

Her involvement with the community extends beyond her professional responsibilities, as she consistently engages in various community initiatives and volunteer efforts. For example, she sponsors a local family each year around Christmas, providing the children with gifts and toys.

It’s through her community involvement that Mariah exemplifies “the qualities of a true leader who is dedicated to making a positive impact both within and beyond her professional sphere,” according to Murray Jenkins.

“Not only does she have an impressive resume of social and community volunteering,” said Alissa Brandt, Vice President of Interiors, “Mariah is someone that, both as a friend and a colleague, will jump in to assist with anything and everything that needs to be done.”

2. Help Others Through Collaboration

Mariah’s commitment to collaborating with her counterparts in Interior Design demonstrates her ability to work seamlessly across disciplines to deliver cohesive and comprehensive design solutions. Her collaborative approach has been pivotal in the successful execution of various projects, enhancing the overall quality and coherence of the firm’s work.

“She will always be there to provide support, guidance, and to honestly jump in and get her hands dirty, taking on any portion of work that needs to be done,” said Alissa Brandt. “Mariah doesn’t ask why. She just asks, ‘How can I help you?’ She treats every ask for help as an opportunity to make us better.”

Her contributions have not only strengthened Ankrom Moisan’s project portfolio but have also played a crucial role in shaping the firm’s culture and values. Her leadership, vision, and collaborative spirit continue to inspire and drive the success of our organization.

3. Set Clear Expectations

One of the notable changes Mariah’s led is the implementation of rigorous project management practices. She has established a culture of excellence by setting clear expectations and standards for design delivery.

“Mariah’s leadership in this area has significantly improved the firm’s project outcomes and client satisfaction,” said Murray Jenkins. “Her meticulous approach ensures that projects are not only completed on time and within budget, but also meet high-quality standards.”

Through her dedication to high standards and her unwavering support for her colleagues, Mariah’s inspired a culture of excellence and continuous improvement at Ankrom Moisan.

4. Participate in Mentorship Opportunities

Mariah consistently gives her time to both local charities and young professionals as a mentor. Her contributions have significantly impacted her colleagues, mentees, and the industry as a whole.

She’s a role model for young professionals in the industry, regularly volunteering her time to provide guidance, support, and professional development opportunities to aspiring architects and designers. She participates in career days, workshops, and mentorship programs, highlighting her commitment to fostering a diverse and inclusive industry.

Her mentorship has helped many individuals navigate their careers and develop their skills, fostering a culture of continuous learning and growth within the firm, resulting in herself being seen as a “go to person at all levels of Ankrom Moisan,” according to Rachel Fazio, Vice President of People.

Within the Office/Retail/Community Studio, she mentors her team members, keeping in mind both the mentoring that she got as a young professional, as well as the mentoring that she wishes she received.

“As a female leader in the firm, Mariah seizes every opportunity to assist emerging professionals, both within the office and beyond,” said Michael Great, Design Director of Architecture. “This dedication is demonstrated by her volunteer work with AFO’s Architects in Schools program and her role as a guest reviewer and contributor at the University of Oregon. She is always willing to share her time and expertise to advance the profession.”

Through these mentoring and leadership efforts, Mariah continues to shape the future of architecture, fostering an environment of innovation, inclusivity, and excellence.

5. Don’t Back Down From a Challenge

According to Dave Heater, Mariah became a team leader “at a young age due to her success at managing some of the most challenging projects for the firm.” Embracing this role with enthusiasm and determination, she was able to foster an inclusive and innovative environment within the Office/Retail/Community studio.

“Mariah has volunteered endlessly at Ankrom Moisan to take on challenges and navigate them back towards success,” said Alissa Brandt. “She steps in to lead teams, clients, and projects.”

In 2021, during a particularly challenging time when the Healthcare studio leader left the firm, Mariah took on additional responsibility as the interim leader of the Healthcare team. She knew that this was a huge lift and that the team/firm needed a large amount of her time to navigate the transition, but she took the challenge on with grace.

“Mariah never alluded to the fact that this was an enormous task,” said Alissa Brandt. “She stepped up and took charge, leading with grace and poise, keeping the entire team moving forward. Without her leadership and commitment, we may not have been able to maintain this extremely important studio in our firm.”

“She consistently goes above and beyond on every project and in every situation,” said Michael Great. “Mariah’s leadership, tenacity, and extensive experience has earned her the respect and admiration of many both inside and outside of Ankrom Moisan. Her unwavering commitment and dedication every day inspires all of us to do better and bring our full selves to every project.”

6. Hold Yourself and Others Accountable

Mariah’s leadership has had a lasting impact on the firm’s operations and has set a benchmark for future leaders to aspire to. Her ability to hold her project managers accountable has instilled a sense of responsibility and ownership across the team. She encourages open communication and transparency, allowing for proactive problem-solving and continuous improvement.

This accountability framework has not only enhanced project performance, but also built a culture of trust and mutual respect within the team.

She’s been instrumental in driving significant changes within the firm, particularly through her rigor in project management and her ability to coach, mentor, and hold her project managers accountable to high standards.

“She created this accountability revolution well before we had studios,” said Dave Heater. “Mariah began tracking key financial metrics on her own to show her team how they were performing. Her efforts are now being replicated at a firm level.”

Mariah at the base of the stairs in Ankrom Moisan’s Portland office.

Congratulations, Mariah, on your recognition as one of 2024’s Women of Vision! You are a role model to the firm, embodying how to make deeper connections and be a better person to work with daily. We are all lucky to call you a coworker.

The Ins and Outs of Adaptive Reuse

What is Adaptive Reuse?

Adaptive Reuse Residential Conversions are projects that repurpose existing buildings for uses other than what the space was originally designed for.

Adaptive reuse offers developers the unique opportunity to save their investment, create and unparalleled story for end users, and make money by converting a disused or underutilized project into a one-of-a-kind residential space.

Chown Pella Lofts, an old factory warehouse converted into a multi-story residential condominium in Portland, OR’s Pearl District.

However, updating old buildings comes with layers of complexity.

Since 1994, Ankrom Moisan has been involved with adaptive reuse projects and housing conversions. The depth of our expertise means we have an intimate understanding of the limits and parameters of any given site – we know what it takes to transform an underperforming asset into a successful residential project.

Why Conversions?

There are many reasons to choose conversion over construction when considering how to revitalize old structures or adapt unused sites.

Rental Housing Demands

According to the National Association for Industrial and Office Parks (NAOIP), the United States needs to build 4.3 million more apartments by 2035 to meet the demand for rental housing. This includes 600,000 units (total) to fill the shortage from underbidding after the 2008 financial crisis. Adaptive reuse residential conversions are an affordable and effective way to create more housing and fulfill that need.

Desirable Neighborhoods

The way we see it, the success of our buildings, neighborhoods, and infrastructure is our legacy for decades to come. Areas with a diverse mix of older and newer buildings create neighborhoods with better economic performances than their more homogeneous counterparts. By preserving and protecting existing structures, conversions contribute positively to the health and desirability of the neighborhood, leading to a quicker tenant fill.

Being committed to the places we occupy, live in, and care about is another reason to embrace adaptive reuse residential conversion projects; they revive our cities. Reducing the number of buildings that sit empty in urban areas plays a major role in activating downtown districts.

Reduced Waste

Saving older, historic buildings also prevents materials from entering the waste stream and protects the tons of embodied carbon spent during the initial construction. AIA research has shown that building reuse avoids “50-75% of the embodied carbon emissions that would be generated by a new building.”

New Marketing Opportunities

Aside from these benefits to the community, adaptive reuse conversions present a way for developers to recover underutilized projects and break into top markets like affordable, market-rate, and student housing.

Construction Efficiencies

Compared to new buildings, residential conversion projects save time, money, and energy, since their designs are based on an existing structure. Adaptive reuse conversions also benefit from not having their percentage of glazing or amount of parking limited by current codes, since they’re already established.

One-of-a-Kind Design

We don’t believe in a magic formula or a linear “one-size-fits-all” approach to composition. Each site is a unique opportunity to establish a one-of-a-kind project identity that’s tied to its history and surroundings.

At the outset of any conversion, we analyze each individual site and tailor our process to align with the existing elements that make it unique. Working with what you have, our designs and deliverables – plans, units, systems narratives, pricing, and jurisdictional incentives – are custom-fit.

It’s our philosophy that you shouldn’t fight your existing structure to get a conversion made; if you can’t fix it, feature it.

Chown Pella Lofts.

Approaching each conversion opportunity with this mindset, we analyze the factors that set a site apart, and embrace those unique elements to ensure a residential conversion stands out. With this intricate and involved process, we’ve been able to get over 30 one-of-a-kind residential conversion projects under our belt.

Through these past experiences, we have identified six key characteristics that make a project a candidate for successful conversion, and six challenges that may crop up during the renovation process. To learn more about what attributes to look out for and what traits to be weary of when considering a residential conversion, read about our “Rule of Six” here.

By Jennifer Sobieraj Sanin, Design Director of Housing and Senior Principal, and Jack Cochran, Marketing Coordinator.

Residential Conversion Case Study

Converted from a Holiday Inn hotel to a residential apartment complex, 728 16th St. embraces its midcentury hotel past while providing a new take on residential housing. By utilizing strategic efficiencies within the renovation process, Ankrom Moisan’s adaptive reuse and renovations design team contained costs, expedited construction, and completed the project in a sustainable fashion.

The Challenge

Originally constructed in the 1970s, the site of 728 16th St. had seen better days. Years of water damage to the roof and walls meant the building’s enclosure needed updating. Additionally, because the structure was originally designed for traveling guests, rather than as permanent lodging, many of the rooms lacked the necessary amenities for residential living, such as kitchen appliances and other utilities like washers and dryers.

Adding these appliances to the space uncovered unique challenges around the inclusion of proper ducts and plumbing for those utilities.

Before: 728 16th St. as a Holiday Inn

The Solution

Leveraging as much of the pre-existing space as possible resulted in the renovated 728 16th St. building’s unified design. Existing structure, utilities, and MEP infrastructure were optimized by the design team to maximize efficiencies and eliminate the need for a complete tear down. In this sense, the name of the game was understanding the parameters of the site and knowing how to work within those parameters to bring the design intent for the new building type to life.

Since the building’s enclosure was updated during the renovation, the design team was given the opportunity to reskin the building with a high performance rain screen system during the update, preventing any further water damage to the structure. This also allowed the team to shift the site’s layout and the location of amenities; the lobby itself was relocated, moved to a more central location of the site.

To increase the total number of units, portions of the existing hotel, such as the parking lot and food service kitchen were infilled and connected to the new lobby. Other existing hotel rooms were combined to create one or two-bedroom apartment units, with an emphasis on maintaining the pre-established bathroom layouts, since they contained plumbing fixtures and pipes that would be too difficult to relocate.

During: A rendering showing what 728 16th St. might look like as a residential housing complex.

Addressing the challenges that were uncovered by the lack of plumbing, pipes, and appliance ducts in the individual new and existing units, the renovations team made large-scale adjustments to the height of the ceilings, to accommodate those appliance ducts and plumbing pipes.

The Impact

By maintaining as much of the original structure as possible and eliminating the need for a tear down, 728 16th St.’s renovation created an expedited development process that ended up being more sustainable than a new build.

After: 728 16th St., converted from a Holiday Inn hotel to residential housing.

Embracing the existing structure, room layouts, and utilities of the Holiday Inn, Ankrom Moisan’s renovations team turned the underutilized hotel space into an affordable-by-design residential project in a desirable area. Shifting the layout and positioning of the site itself allowed 129 new units to be built, both increasing the amount of available housing in the area and diversifying the unit types within 728 16th St., as the original design was repetitive.

The fresh perspective on modern residential housing brought to life by the Ankrom Moisan adaptive reuse conversion team sets 728 16th St. apart as a place that remains competitive in new markets.

Overall, the building type conversion for this project was successful because the site exhibited at least two of the six key characteristics for effective renovations, otherwise known as the “Rule of Six.” Being situated in a walkable location and having at least a 12,000 square foot plate set 728 16th St. up for success, but a prospective adaptive reuse conversion truly only needs one of the six key characteristics to be a qualified candidate for successful conversion. Read more about the Rule of Six and how to tell if your site would make for a successful residential conversion here.

For guidance through the adaptive reuse process, contact Jennifer Sobieraj Sanin, Housing Studio Design Director and residential conversion expert.

By Jennifer Sobieraj Sanin, Housing Studio Design Director.

Contact: +1 (206)-576-1600 | jennifers@ankrommoisan.com

Should Your Building Become Housing? Critical Considerations for Adaptive Reuse

It’s the question on every developer’s mind right now. Is adaptive reuse feasible for my building? Cost-effective? What will a housing conversion project entail?

Since 1994, Ankrom Moisan has been involved with adaptive reuse projects and housing conversions. The depth of our expertise means we have an intimate understanding of the limits and parameters of any given site – we know what it takes to transform an underperforming asset into a successful residential project.

For customized guidance through the adaptive reuse evaluation process, contact Jennifer Sobieraj Sanin, Housing Studio Design Director and residential conversion expert.

The Rule of Six

While there is no magic formula or linear ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to conversions, we have a framework that should be considered when approaching an adaptive reuse project. We call it “The Rule of Six.”

The Rule of Six outlines six key characteristics that make a project a candidate for successful conversion, and six challenges to be prepared for during the renovation process.

With this informed process, we’ve been able to get over 30 one-of-a-kind residential conversion projects under our belt.

The Six Key Characteristics for a Successful Conversion

Not every building is a good candidate for conversion. By evaluating multiple structure types and working closely with contractors on successful projects, we’ve identified six key characteristics that lead to the creation of successful, low-cost, conversions.

If a property has any of these traits – whether it’s one characteristic of all six – it might qualify as a candidate for a successful conversion.

- Class B or C Office

- 5-6 Levels, or 240′ Tall

- Envelope Operable Windows Preferred

- Walkable Location

- 12,000 Sq. Ft. Plate Minimum

- Depth to Core Not to Exceed 45′

To find out if a property makes for a good adaptive reuse project, consider conducting a feasibility study on the site.

Reach out to get started on your feasibility study today.

The Six Challenges to be Prepared For

West Coast conversions can be particularly challenging with their seismic requirements, energy codes, and jurisdictional challenges – your conversion team should be prepared for these hurdles. The solutions vary by project; contact us to see how we can solve your project’s challenges.

- Change of Use: It’s the reason we upgrade everything. The simple act of changing a building’s use from office to residential immediately triggers a ‘substantial alteration.’ This label starts all the other necessary upgrades.

- Seismic-structural Upgrades: Buildings on the West Coast must meet a certain code level to be deemed acceptable for the health, safety, and welfare of end-users. Often, this required level does not match the current code, meaning negotiations with the jurisdiction are necessary.

- Egress Stairs: Stair width is usually within the code demands for conversion candidates, but placement is what we need to evaluate. When converting to residential, it’s sometimes necessary to add a stair to the end of a corridor.

- Envelope Upgrades and Operable Windows: West Coast energy codes require negotiated upgrades with jurisdictions, as existing envelopes usually don’t meet the current codes’ energy and performance standards. Operable windows are a separate consideration. They are not needed for fresh air but are often desired by residents for their comfort.

- Systems and Services Upgrades: These upgrades often deal with mechanical and plumbing – checking main lines and infrastructure, decentralizing the system, and adding additional plumbing fixtures throughout the building to support residential housing uses.

- Rents and Financials: Determining how to compete with new build residential offerings is huge. At present, conversions cost about as much as a new build. Our job is to solve this dilemma through efficient and thoughtful design, but we need development partners to be on the same page as us, knowing where to focus to make it work.

At the outset of any conversion, we analyze each individual site and tailor our process to align with the existing elements that make it unique. Working with what you have, our designs and deliverables – plans, units, systems narratives, pricing, and jurisdictional incentives – are custom-fit.

To better understand if adaptive reuse is right for your building, get in touch with us. We can guide you through the feasibility study process.

To see how we’ve successfully converted other buildings into housing, take a look at our ‘retro residential conversion’ case study.

By Jennifer Sobieraj Sanin, Housing Studio Design Director.

Contact: +1 (206)-576-1600 | jennifers@ankrommoisan.com

What You Need to Know About Biophilic Design

Biophilia is the concept that there is an innate connection between humans and nature. Our love of nature and tendency to crave connections with the natural world is a deeply engrained and intuitive aspect of both human psychology and physiology. It’s part of our DNA.

Building off that concept, biophilic design is the intentional use of design elements that emulate sensations, features, and phenomena found in nature with the goal of elevating the built environment for the benefit of its end users.

Simply put, biophilic design is good design. It doesn’t have to be expensive or elaborate; it just has to be intentional. Creating connections to the outdoors in the built environment can significantly impact users’ mental and physical well-being.

How Biophilia is Integrated into Projects

There are many ways to integrate biophilic elements into a project’s design. Some of the most common methods of doing this have been categorized by the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) as being either Nature in the Space, Natural Analogues, or the Nature of the Space.

1. Nature in the Space

Biophilic design that places emphasis on bringing elements of the outdoors into interior spaces would be classified as ‘Nature in the Space.’ These outdoor-elements-brought-inside can be anything from plants, animals, and water features, to specific scents, sensations (like the feeling of a breeze), shade and lighting effects, or other environmental components found in the natural world. They are organic features that are literally brought inside. An example of this could be a project using natural materials like exposed mass timber and green walls covered with living plants to mimic the sensation of being in a wooded forest.

2. Natural Analogues

‘Natural Analogues’ in biophilic design are human-made, synthetic patterns, shapes, colors, and other details that reference, represent, or mimic natural materials, markings, and objects without utilizing or incorporating those actual materials, markings, or objects. An example of a natural analogue might be the use of spiral patterns in a painted wall mural to link a project’s design to seashells and the coast, the inclusion of animal print motifs in fabric and material choices, or even the use of blue rugs and carpeting to link a site to a nearby river or other body of water. Subtle finishes, fixtures, and equipment (FF&E) touches can also be a biophilic natural analogue, like the use of shelves that reference the pattern and shape of a honeycomb. Natural analogues are most often design and material choices that pay homage to recognizable environmental elements.

3. Nature of the Space

A focus on the ‘Nature of the Space’ on the other hand, pays more attention to a location’s construction, layout, and scale than its FF&E and other accessories or interior design. It utilizes spatial differences, the geography of a space, and other elements of a project’s configuration to imitate expansive views, sensory input, or even feelings of safety and danger that are found in the wild. This may manifest as an open stairwell that embraces rough, asymmetrical walls to subtly mirror the textures of a canyon, or as the inclusion of an atrium to give end-users a perspective that parallels the wide-open views seen from a mountain peak. ‘Nature of the Space’ can also be seen in the use of soft lighting and smaller scale spaces to simulate the felt safety and coziness of a cave. It is the utilization of a project’s site itself to replicate experiences and sensations found in the world of nature.

By emulating natural features and bringing the outdoors in, architects and interior designers integrate the benefits of exposure to the natural world into built spaces, creating a unique shared experience for a site’s users.

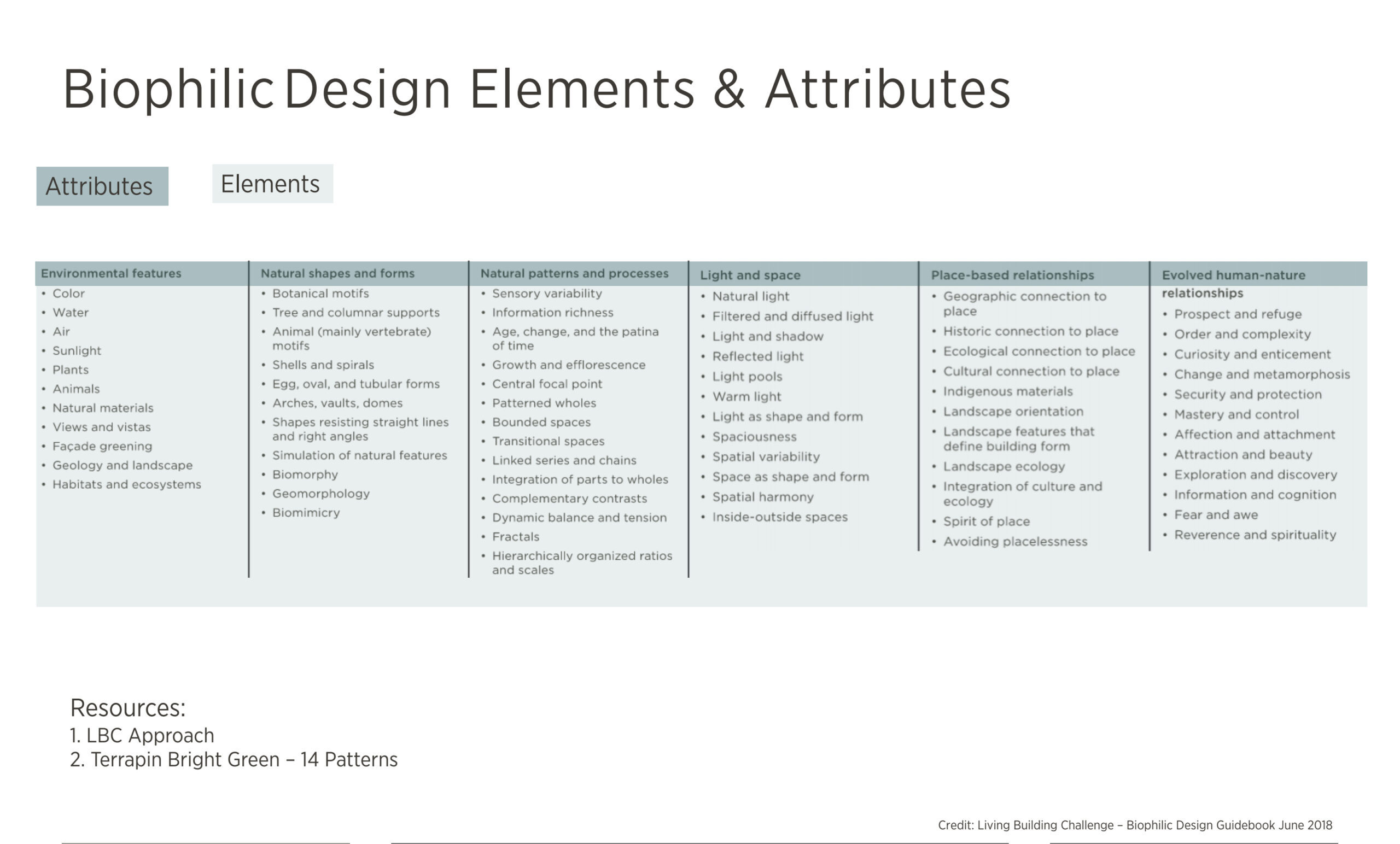

A list of biophilic design elements and attributes.

When combined with intentionality and thoughtful design, these elements can transform ordinary spaces into spaces that support human health and wellness.

The Power of Biophilia

Aside from elevating design, the inclusion of biophilic elements in a project can have numerous positive health benefits for those who use and inhabit that space. Biophilia’s impact on health and wellness may not be something that we are conscious of, but it is a difference that we feel. Humans understand biophilia intuitively.

The amount of time humans spend interacting with nature – as well as the amount of time they are disconnected from the natural world – has real, tangible impacts on an individual’s health. In today’s industrial, technologically dominated world, it’s especially important to seek out connections with nature, since many built spaces often forgo biophilic features and the benefits that come with them.

The negative health impacts of not having enough connection to nature are:

- High blood pressure

- Muscle tension

- Anxiety

- Poor sleep stemming from an unstable circadian rhythm

- A weakened immune system

- Poor focus

- Weak memory

- Attention issues like ADHD

- Fatigue

- Decreased emotional regulation

The positive benefits of exposure to nature, on the other hand, include:

- Lower blood pressure

- Muscle relaxation

- Feelings of safety

- Restful sleep and a stable circadian rhythm

- A strong immune system

- Increased focus

- Greater memory and learning abilities

- Higher energy levels

- Increased emotional regulation

Knowing the range of benefits that biophilia has the potential to provide, architects and interior designers have the opportunity to purposefully design spaces with the health and wellbeing of its end-users in mind, positively influencing the experience of a location as well as the feelings of the people occupying it.

Some of Ankrom Moisan’s expert design teams have already done this, including biophilic elements in the shared spaces of project to elevate the end-user’s experience of those environments. In a follow up blog post, we will take a deeper look at how biophilia shows up in three distinct Ankrom Moisan healthcare projects, discussing how the inclusion of biophilia can be leveraged to support an evidence-based approach to holistic, whole-person care.