Held at the beginning of each year, our annual People Celebration is a time when the firm reflects, looking back at all we have accomplished in the last year and honoring those who have helped to get us where we are. As a part of that celebration, we aim to acknowledge and reward the hard work of the individuals who have really made a difference in the part year.

We are pleased to announce the promotion of 18 team members who have demonstrated a strong commitment to designing smarter and going beyond for their clients and communities.

2025’s Promotion Recipients

Promoted to Senior Director

- Emily Lamunyan – Senior Director of Marketing

Promoted to Studio Co-Leader

- Brad Bane – Affordable Housing Studio Co-Leader

Promoted to Principal

- Cara Godwin – Principal, Operational Excellence, Practice

- Jason Jones – Principal, Higher Education Studio Co-Leader

- Katie Lyslo – Principal, Affordable Housing Studio Co-Leader

- Ashlee Washington – Principal, Healthcare Studio Co-Leader

Promoted to Associate Principal

- Kimberly Gonzales – Associate Principal, Office/Retail/Community

Promoted to Senior Associate

- Aaren DeHaas – Senior Associate, Office/Retail/Community

- Richard Grimes – Senior Associate, Senior Communities

- Alex Kuzmin – Senior Associate, Higher Education

- Jenna Mogstad – Senior Associate, Higher Education

- Scott Soukup – Senior Associate, Senior Communities

- Elisa Zenk, LEED AP BD+C – Senior Associate, Affordable Housing

Promoted to Associate

- Angela Blechschmidt – Associate, The Society

- Sydney Ellison – Associate, Higher Education

- Mandy Housh – Associate, Senior Communities

- Anders O’Neill – Associate, Marketing

Celebrating a culture of leadership, collaboration, and innovation, these promotions recognize individuals who not only push the boundaries of design and expertise, but also foster an environment where mentorship, inclusivity, and creativity thrive.

“Their contributions strengthen our studios, enrich our firm, and shape the future of the communities we serve,” Dave Heater, President, said of the individuals who received promotions this year. “We look forward to the continued impact they will make – both within our teams and in the spaces we create.”

Congratulations to everybody who received a promotion – it is well-deserved, and your hard work is appreciated!

Employee Spotlight: 2024 Q2 HOWNOW Champion Matthew Poncelow

Just past his ten-year anniversary with the firm, Matthew Poncelow, Senior Project Manager, sees the hidden connections between a project, its intended users, and the team of designers creating it, using Ankrom Moisan’s HOWs to stay on top of those threads, manage what needs to be done, and identify opportunities for collaboration across teams. He chooses his own adventure, supporting those he works with along the way.

Matthew Poncelow.

Matthew initially came to Ankrom Moisan from Santa Fe, New Mexico, relocating to the Pacific Northwest because of his desire to pursue housing work. He recalls his job search, saying “Ankrom Moisan was the most welcoming and seemed to have the best culture. They were also working on project types I wanted to be involved with, so it seemed like a perfect fit.”

Now, a decade later, Matthew has seen a lot of change within the firm and architecture industry at large. “When I first started, it was very different,” he shared. We were still in the old building on Macadam Ave. Tom Moisan was still very much involved in the daily things going on in the office. It was a time of growth. There was lots of hope, and lots of future project prospects. It was just a really exciting time to be here.”

Matthew noted how interesting it has been to see how we work move into the digital sphere. “When I started, there was still a lot of paper around the office. There were piles of drawings and still lots of physical media,” he said. “We don’t have that anymore – it’s all online. Our visualization has advanced so far, too. Now we have things like Enscape where you have a real-time rendering that you can engage with in virtual reality. I’m looking forward to seeing what the technology does over the next ten years.”

“It’s funny,” he added. “As I’ve gotten older, it’s gotten harder and harder to embrace change. We get used to doing things a certain way. After doing it that way a few times, we think we know what to do. That’s why I think that embracing change, while being the hardest HOW to embrace, is probably one of the most important of our values, since it’s the only way one can grow.”

Matthew (center) at the 2022 AM holiday party

Adapting to industry-wide changes and gaining a better understanding of the architectural process along the way, Matthew attributes his ability to see how the different parts and pieces of the architectural process come together to his position as a Senior Project Manager. “I’m very lucky. I’m able to start at the very beginning with the developer and feasibility studies on many projects and am also there at the end when we’re opening the building and people are moving in,” he said. “Being able to see the whole spectrum from start to finish is really what architecture is about to me.”

While the prospect of working on housing is what attracted Matthew to Ankrom Moisan, our firm’s culture, and the people who make it up, is what has kept him here. “There are a lot of great people at Ankrom Moisan,” Matthew stated. “The people who work here genuinely care about each other.” He continued about the atmosphere of encouragement at Ankrom Moisan, saying, “I think that there’s a lot of room for professional growth here. It’s a ‘choose-your-own-adventure’ place to work. If you’re interested in something or have a passion about something, very often, the firm will support you in becoming more of an expert in that area.”

“You will get out of Ankrom Moisan what you put into it,” he said. “Listen; Learn; Watch what others are doing and you will see our HOWs manifested in the people around you. By just participating, ways to embrace our HOWs will show up. Get involved and be a part of it.”

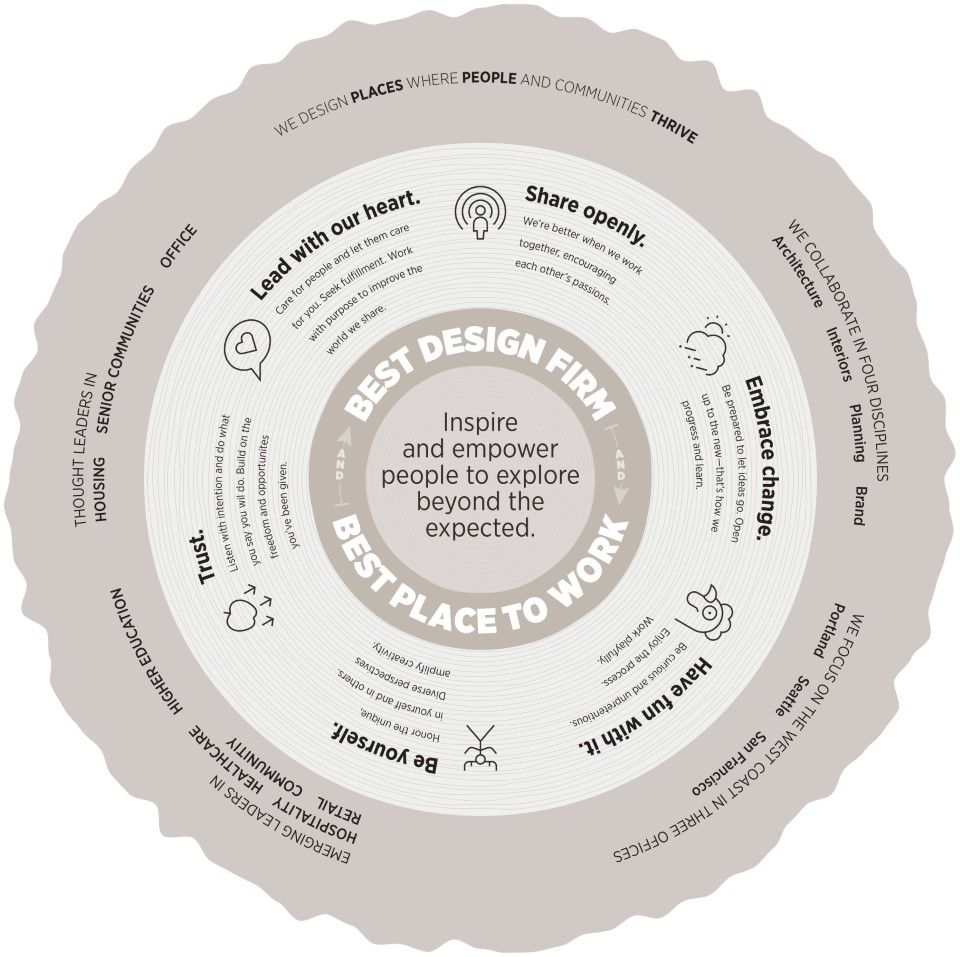

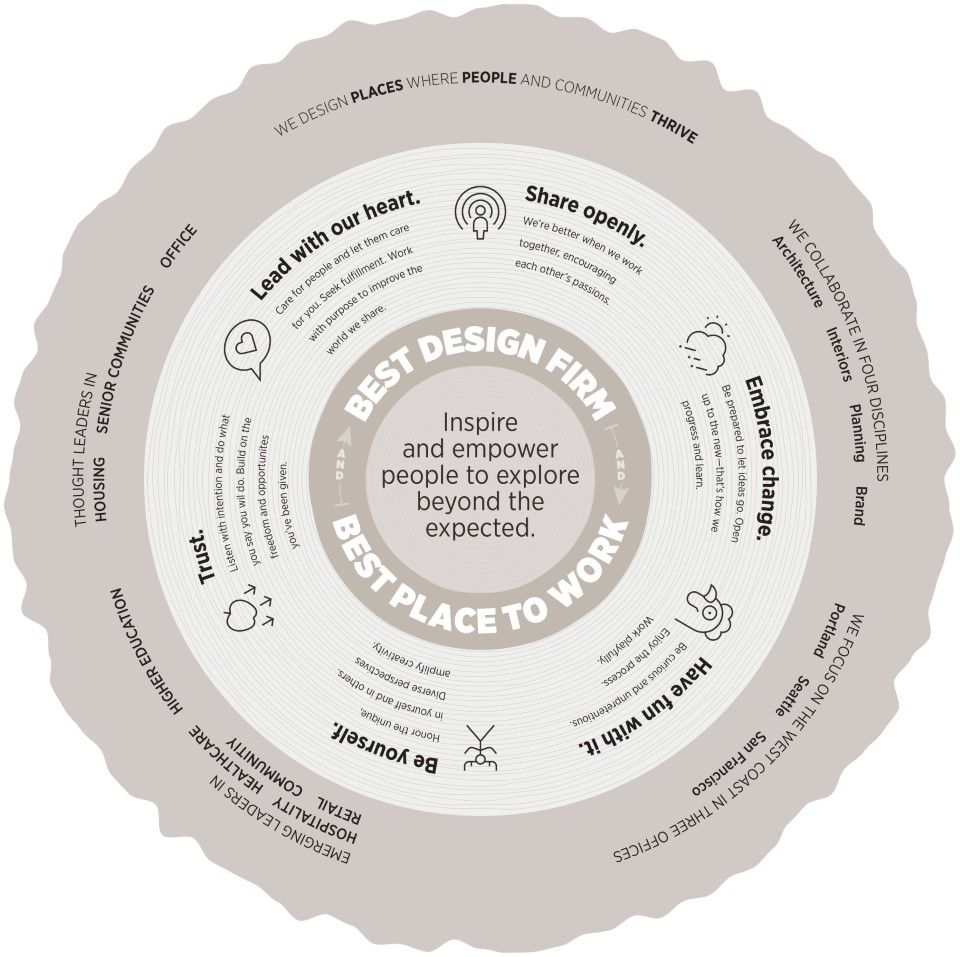

Ankrom Moisan’s HOWs

With that perspective in mind, Matthew is very satisfied with the adventure he’s chosen in housing. “The scale of projects is interesting to me,” he shared. “I like working on larger scale projects.” Specifically, Matthew loves doing fire stations. “They are some of the most well-organized folks out there. They know what they want, and they make decisions quickly,” he said. “I find that the impact of doing multifamily housing and being involved in bigger jurisdictions – providing housing to lots of people where it’s needed – is very satisfying.”

Matthew on the roof of Ankrom Moisan’s Portland office.

Finding inspiration for a new project is another aspect of housing that Matthew finds satisfying. “A lot of that early work on a project is learning about the site and the community it will serve, as well as learning about the history and geology of the site,” he said. “I find that very inspiring, and I enjoy the challenge of figuring out how to take a complicated set of requirements and make them real. The depths and processes that go into creating impactful architecture inspires me quite a bit.”

Because there are often many different moving parts that go into the process of creating an impactful project, Matthew shared that success comes easiest when people are at the top of their game, “when we’re all doing our part and functioning like a well-oiled machine.”

Recognized by David Kelley, Housing Studio Director, in his nomination video for his excellent leadership, cool head, and commitment to quality work, Matthew acknowledged the significance of Ankrom Moisan’s HOWs in influencing his work ethic and communication style. “It all really starts with leading from the heart,” he explained. “It brings me great joy to be problem solving and caring for people and communities by trying to create wonderful places for them to live and thrive – in my mind, quality work is the way to show that, and I think that my quality of work is a direct reflection of all the people I work with. I would not be able to do the quality of work that I do if it wasn’t for the other people around me. There’s a lot about sharing values openly that contributes to that. And like I said, I love it. I’m having fun with this. I enjoy the process. I’ve wanted to work in architecture ever since I was a kid. For all these reasons, I’m led to want to do my best, highest quality work.”

Matthew’s nomination video

Don Sowieja, Housing Studio Leader, also recognized Matthew’s ability to balance multiple projects in his nomination video, something that Matthew attributes to his understanding of the architectural process. “Working on multiple projects under multiple different phases of construction is something that is simplified by having systems and standards in place. It makes it easier to deal with unknowns on a project and quickly shift gears when you know that the foundation or base is there.”

For example, Matthew makes lists and sheets to keep track of what is happening on a project at any given time. “Being disciplined and maintaining these systems makes it so that if someone calls me up and asks about something, I know where to look to figure out the answer,” he said. He pointed out that it’s the same way with our drawings, saying “the reason why we do the drawings the way we do is because there’s consistency and a system there. The line weights have meanings based on these systems, creating that understanding. That’s the only way to be able to handle as much complex information as we do, being able to have these different standards.” It’s Matthew’s trust of systems and standards, and his open sharing of information to secure a project’s success that earned him the title of Q2 HOWNOW Champion.

When Matthew found out about his recognition as the Q2 HOWNOW Champion, he felt seen. Working remotely and traveling to project sites, his time is often split between his home office, project sites, and Ankrom Moisan’s Portland and Seattle offices. “I’m kind of always coming and going,” he said. “To know that even thought I’m not present there with everyone, I’m still being noticed for the work that I’m doing is something that I’m very appreciative of.”

He hopes that the Rewards and Recognition program serves as a reminder of the values that this company was founded on, rather than just being a regular ’employee of the month’ type of recognition. “When I found out I was being honored, I sat down for a second to look at the value wheel on our website and think about them for a good minute,” he said. “It’s my hope that the legacy of this program is a good reminder of our HOWs and what our core ideas and philosophies are. I hope it ensures that the core tenants of what we’re trying to do stay alive and don’t just become a webpage that nobody looks at.”

Matthew’s Rewards and Recognition banner

Meditating on the idea of Ankrom Moisan being a ‘choose-your-own adventure,’ Matthew has a lot of advice for younger, emerging professionals. He stresses the importance of asking questions, stating that people who ask questions “create opportunities for us all to grow, which is something we must be careful not to lose in the new world of remote work.” He goes on to say that it’s important to be a helper and a problem solver, as “a willingness to get involved and do what needs to be done will serve one well through all the different parts of their career. People look for helpers and problem solvers – if you focus on being one, you will be presented with many opportunities.”

Some of those opportunities should not be taken for granted according to Matthew, such as the opportunity architects have daily to make an impact on the world around us. “Something that I try to impart on younger staff members who work with me is that we are literally changing the world and changing our environment in so many ways,” he said. “It’s important to remember that we can do amazing, difficult things, even if there are problems and roadblocks along the way.”

Undoubtedly, Matthew uses Ankrom Moisan’s HOWs to overcome any roadblocks that cross his path, allowing him to continue to make a difference to the world around him by providing quality housing to those who need it.

Rocking for a Cause

CCC

Since 1979, Central City Concern has helped struggling individuals overcome barriers such as lack of affordable housing, health care and living-wage jobs, systemic racism, mental health challenges, chronic health conditions, substance abuse disorders, and time spent in the justice system. Their approach addresses both the systemic drivers of homelessness and the individual factors that can reinforce it, and their foundational belief is in the restorative powers of human connection and dignity. It’s with this lens that the mission goal of ending homelessness by treating the whole person emerged. Helping upwards of 15,000 individuals every year, they offer services that range from housing, healthcare and recovery to employment assistance and other culturally specific support.

CCC Cedar Commons

Sharing this vision of ending homelessness by creating connected communities where all our neighbors have access to housing, health, and economic opportunities, we have collaborated with CCC on many projects since 2016’s Cedar Commons. Like many of the other projects done in collaboration with Central City Concern, Cedar Commons is a mixed-use affordable housing complex dedicated to building community and offering compassionate support to those struggling with addiction, lack of housing, or mental health issues, helping them become self-sufficient and productive. It was also the start of a years-long collaborative relationship.

Amanda Lunger’s “You Down With CCC” rap video

Reflecting upon the long working relationship between Ankrom Moisan and Central City Concern, Mariah Kiersey, Co-Leader of the Office / Retail / Community Studio, shared that “from the Blackburn Center to 1616 Burnside and Meridian Gardens, we have been collaborative with CCC to provide the spaces to treat the whole person for years. This fundraiser was another fun way for us to help spread the word of all that CCC does within Old Town and across Portland.” She finished, hoping, “we look forward to future collaborations in fundraising, volunteering, donations, and of course, amazing design work together!”

Jenna Mogstad, a designer who has worked on many of Ankrom Moisan’s collaborations with Central City Concern, noted how AM’s relationship with CCC “began with the Blackburn Center and has only grown stronger.”

CCC Blackburn

“CCC and Ankrom Moisan have always had a similar mission to create homes for those who need them most,” Jenna said. “Every project has provided new insight and lessons learned into what is going to be best for future residents, which has only made our process more efficient and fun. They’re much more than a client to us – they’re a partner. We know the work they do is invaluable, and we want to do as much as we can to continue to support that mission and make an impact within our community. Whether that means volunteering our time after-hours or taking extra steps to provide a unique or meaningful project, Central City Concern have always allowed us to participate in their efforts to make a difference. This includes hosting events like jAM, where we can truly make fundraising fun!”

Featured in Give!Guide, Willamette Week’s yearly collection of local nonprofits, charities, and fundraisers for Portlanders to donate to, CCC plugged their goal of raising $100,000 while speaking highly of us and our longstanding relationship, saying “everyone deserves to feel safe and proud of where they live, and Ankrom Moisan has been invaluable in helping CCC accomplish this goal – creating spaces designed for a lifetime of growth, with “home” as their guiding principle. We’re thrilled to partner with Ankrom Moisan for this year’s Give!Guide campaign.”

The jAM

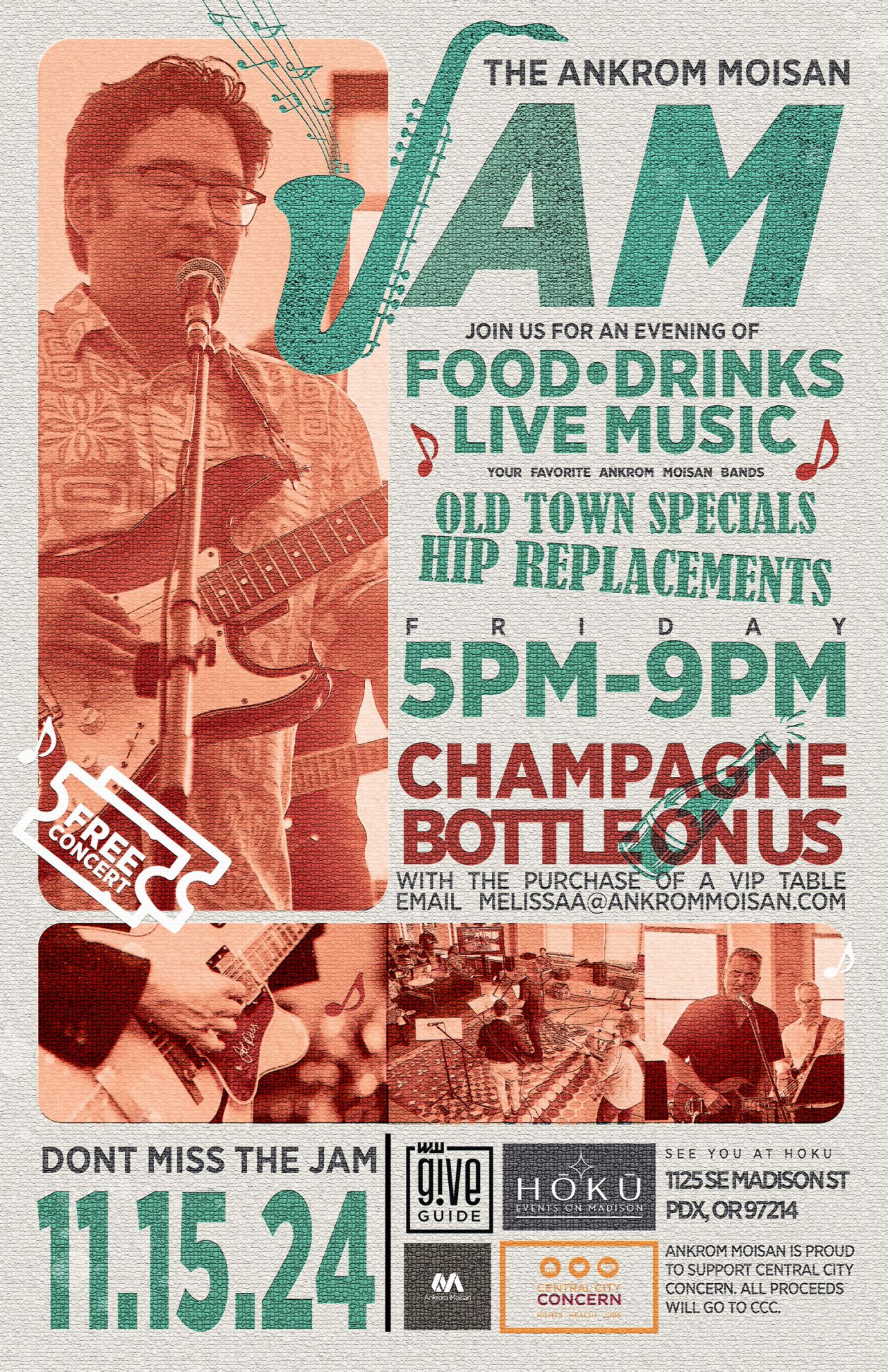

Promotional poster for the jAM fundraising concert

Combining Ankrom Moisan’s cherished “pickathon” showcase of AM’s staff musicians with our yearly fundraiser for the first time, 2024’s jAM event was a rocking, rolling success. Partnering with Portland-based nonprofit Central City Concern (CCC) to support their mission of providing affordable, supportive housing to those who need it, about 100 individuals from Ankrom Moisan, CCC, and elsewhere danced and sang along to live music performed by two of Ankrom Moisan’s very own house bands, raising money while having fun and enjoying some delicious food and drink in Southeast Portland’s Hoku event space.

Ryan Miyahira, Co-Director of the Senior Communities Studio, member of both The Old Town Specials and The Hip Replacements, and a key organizer of jAM said about the event, “it’s really exciting we got two companies that have worked together on some of these really great, innovative projects to support the homeless and people in need.”

The Old Town Specials playing “Feelin’ Alright?” by Joe Cocker

The festivities were kicked off on Friday, November 15th by The Old Town Specials, featuring Stephanie Baker on vocals, George Signori, Juan Conci, Ryan Miyahira, and Adam York on guitars, Don Sowieja on bass, and Justin Johnson on drums. They played a high-energy set to a crowd of dancing Ankrom Moisan-ers before Maya Edelstein, Interim Director of Development for Central City Concern came out on stage to give a word about how our work building affordable, supportive housing for those in need has been integral to supporting CCC’s mission.

“Ankrom Moisan has been a critical partner in Central City Concern’s efforts, collaborating on innovative projects like Cedar Commons and the Blackburn Center, but our work together doesn’t end there,” Maya shared. “Like CCC, Ankrom Moisan understands the importance of a place to call home, and they embody this value by showing up for the organization and our clients at every turn. Given that Ankrom Moisan is made up of remarkably creative people, it didn’t surprise us that they found a way to support our Give!Guide campaign with the jAM fundraiser. By putting their talents on display, Ankrom Moisan’s staff created a fun, warm-hearted environment to encourage giving. We’re so grateful for everyone’s efforts in making the fundraiser a success.”

Featuring the talents of Ryan and Lara Miyahira, Justin Johnson, Pete Abrams, Grant Gascon, and John Chase, The Hip Replacements took to the stage to close out the night, playing funky, energetic covers of Prince and Gloria Gaynor, among other saxophone-infused toe-tappers.

At the jAM event alone, we were able to raise $2,700 in donations for Central City Concern, just over 2.5% of their total goal for the Give!Guide fundraiser. To help CCC reach their goal of providing services that support struggling individuals throughout Portland, donations can be made through Willamette Week’s Give!Guide, here, until December 31st, 2024, or directly to Central City Concern, here.

Six Lessons Inspired by 2024 DJC Women of Vision Honoree Mariah Kiersey

Held annually, the Daily Journal of Commerce (DJC) Women of Vision award recognizes and honors women who are shaping the built environment with their technical skill, leadership, mentoring, community involvement, and creation of opportunities for future generations of women in the industries.

Nominated by her peers, Senior Principal and Office/Retail/Community Studio Co-Leader Mariah Kiersey was selected by the DJC as an honoree for her contributions to Ankrom Moisan and the greater Portland community.

Mariah Kiersey celebrates her recognition as a Woman of Vision in Ankrom Moisan’s Portland office.

The epitome of a strong female leader, Mariah consistently demonstrates exceptional leadership, creativity, and dedication to both her craft and team. According to Murray Jenkins, Vice President of Architecture, “her ability to inspire and guide her team has significantly contributed to our firm’s success and reputation in the industry. She consistently demonstrates a commitment to excellence and a passion for mentoring others.”

However, Mariah’s contributions to our firm extend beyond her role as Co-Leader of the Office/Retail/Community studio; she is a trusted colleague and an inspiring leader who fosters an environment of innovation and inclusivity.

Within Ankrom Moisan, Mariah is “one of those rare architects who have an incredible amount of grit,” said Dave Heater, President. “This shows up in how hard she works and how much she cares about doing great work for her clients and helping those on her team learn and grow.”

One of her many contributions to the firm in this sense are the lessons she imparts – knowingly or unknowingly – to the rest of the firm. Here are six lessons on how to be an employee of vision, inspired by Mariah and her award-winning work ethic.

1. Get Involved

Mariah is a passionate advocate for community health, often volunteering her time and expertise to support local initiatives aimed at providing essential services to individuals facing mental health challenges. Her work in designing and developing behavioral health facilities reflects her deep understanding of the critical role that well-designed spaces play in supporting mental health and wellbeing.

Her involvement with the community extends beyond her professional responsibilities, as she consistently engages in various community initiatives and volunteer efforts. For example, she sponsors a local family each year around Christmas, providing the children with gifts and toys.

It’s through her community involvement that Mariah exemplifies “the qualities of a true leader who is dedicated to making a positive impact both within and beyond her professional sphere,” according to Murray Jenkins.

“Not only does she have an impressive resume of social and community volunteering,” said Alissa Brandt, Vice President of Interiors, “Mariah is someone that, both as a friend and a colleague, will jump in to assist with anything and everything that needs to be done.”

2. Help Others Through Collaboration

Mariah’s commitment to collaborating with her counterparts in Interior Design demonstrates her ability to work seamlessly across disciplines to deliver cohesive and comprehensive design solutions. Her collaborative approach has been pivotal in the successful execution of various projects, enhancing the overall quality and coherence of the firm’s work.

“She will always be there to provide support, guidance, and to honestly jump in and get her hands dirty, taking on any portion of work that needs to be done,” said Alissa Brandt. “Mariah doesn’t ask why. She just asks, ‘How can I help you?’ She treats every ask for help as an opportunity to make us better.”

Her contributions have not only strengthened Ankrom Moisan’s project portfolio but have also played a crucial role in shaping the firm’s culture and values. Her leadership, vision, and collaborative spirit continue to inspire and drive the success of our organization.

3. Set Clear Expectations

One of the notable changes Mariah’s led is the implementation of rigorous project management practices. She has established a culture of excellence by setting clear expectations and standards for design delivery.

“Mariah’s leadership in this area has significantly improved the firm’s project outcomes and client satisfaction,” said Murray Jenkins. “Her meticulous approach ensures that projects are not only completed on time and within budget, but also meet high-quality standards.”

Through her dedication to high standards and her unwavering support for her colleagues, Mariah’s inspired a culture of excellence and continuous improvement at Ankrom Moisan.

4. Participate in Mentorship Opportunities

Mariah consistently gives her time to both local charities and young professionals as a mentor. Her contributions have significantly impacted her colleagues, mentees, and the industry as a whole.

She’s a role model for young professionals in the industry, regularly volunteering her time to provide guidance, support, and professional development opportunities to aspiring architects and designers. She participates in career days, workshops, and mentorship programs, highlighting her commitment to fostering a diverse and inclusive industry.

Her mentorship has helped many individuals navigate their careers and develop their skills, fostering a culture of continuous learning and growth within the firm, resulting in herself being seen as a “go to person at all levels of Ankrom Moisan,” according to Rachel Fazio, Vice President of People.

Within the Office/Retail/Community Studio, she mentors her team members, keeping in mind both the mentoring that she got as a young professional, as well as the mentoring that she wishes she received.

“As a female leader in the firm, Mariah seizes every opportunity to assist emerging professionals, both within the office and beyond,” said Michael Great, Design Director of Architecture. “This dedication is demonstrated by her volunteer work with AFO’s Architects in Schools program and her role as a guest reviewer and contributor at the University of Oregon. She is always willing to share her time and expertise to advance the profession.”

Through these mentoring and leadership efforts, Mariah continues to shape the future of architecture, fostering an environment of innovation, inclusivity, and excellence.

5. Don’t Back Down From a Challenge

According to Dave Heater, Mariah became a team leader “at a young age due to her success at managing some of the most challenging projects for the firm.” Embracing this role with enthusiasm and determination, she was able to foster an inclusive and innovative environment within the Office/Retail/Community studio.

“Mariah has volunteered endlessly at Ankrom Moisan to take on challenges and navigate them back towards success,” said Alissa Brandt. “She steps in to lead teams, clients, and projects.”

In 2021, during a particularly challenging time when the Healthcare studio leader left the firm, Mariah took on additional responsibility as the interim leader of the Healthcare team. She knew that this was a huge lift and that the team/firm needed a large amount of her time to navigate the transition, but she took the challenge on with grace.

“Mariah never alluded to the fact that this was an enormous task,” said Alissa Brandt. “She stepped up and took charge, leading with grace and poise, keeping the entire team moving forward. Without her leadership and commitment, we may not have been able to maintain this extremely important studio in our firm.”

“She consistently goes above and beyond on every project and in every situation,” said Michael Great. “Mariah’s leadership, tenacity, and extensive experience has earned her the respect and admiration of many both inside and outside of Ankrom Moisan. Her unwavering commitment and dedication every day inspires all of us to do better and bring our full selves to every project.”

6. Hold Yourself and Others Accountable

Mariah’s leadership has had a lasting impact on the firm’s operations and has set a benchmark for future leaders to aspire to. Her ability to hold her project managers accountable has instilled a sense of responsibility and ownership across the team. She encourages open communication and transparency, allowing for proactive problem-solving and continuous improvement.

This accountability framework has not only enhanced project performance, but also built a culture of trust and mutual respect within the team.

She’s been instrumental in driving significant changes within the firm, particularly through her rigor in project management and her ability to coach, mentor, and hold her project managers accountable to high standards.

“She created this accountability revolution well before we had studios,” said Dave Heater. “Mariah began tracking key financial metrics on her own to show her team how they were performing. Her efforts are now being replicated at a firm level.”

Mariah at the base of the stairs in Ankrom Moisan’s Portland office.

Congratulations, Mariah, on your recognition as one of 2024’s Women of Vision! You are a role model to the firm, embodying how to make deeper connections and be a better person to work with daily. We are all lucky to call you a coworker.

Employee Spotlight: 2024 Q1 Employee Ownership Champion Stephanie Hollar

Honored as a champion of employee ownership within the first round of Ankrom Moisan’s rewards & recognition program, Stephanie Hollar sees the greater whole of our efforts and embraces teamwork to make a difference.

Stephanie Hollar’s headshot.

Stephanie first came to Ankrom Moisan at the behest of her then-boyfriend (now husband). It was over a decade ago, back in 2013. She was living in Washington state and wanted to make the move down to Portland “My husband recommended that I reach out to Ankrom Moisan because he knew Amanda Lunger,” Stephanie explained. “They were friends in college, and since he knew I was interested in housing, he thought this would be a good spot for me. I sent my portfolio to Amanda, and that’s how I got my foot through the door.”

When she started at Ankrom Moisan, getting through the rest of the door, Stephanie recalled that it was a really exciting time. “We were doing lots of projects in Portland, and there was a lot of hiring. We hired quite a few people who were just right out of college,” she said. “It was fun to start with a bunch of people who were in the same boat as me, carrier-wise.”

In addition to the excitement of starting her first post-grad job with a group of similarly aged coworkers, Stephanie found lots of stimulation in her work. She described her first project, Goat Blocks, as “cool, interesting, and exciting,” due to its location just a quick bike ride away from where she was living at the time. Now, over ten years later, Stephanie is still just as passionate about the work she does as a Technical Designer, doing CA (Construction Administration, AKA Administration of the Contract for Construction) work on affordable housing projects. “I just love the reason behind doing affordable housing,” Stephanie said. “There’s absolutely a housing crisis going on. Being able to feel like you’re doing something to help fix that is really nice.”

Stephanie’s recognition banner.

Having worked consistently to make an impact on the housing crisis with Ankrom Moisan’s affordable housing team, Stephanie knows that she’s grown a lot in her time at the firm. “I’ve become a lot more confident over the years,” she said. “Confident and more comfortable asking questions and stepping into conversations, especially as a woman. It can be hard to bring your voice to the table when it’s all just men, but that’s something I’ve become more comfortable and confident with, with age and experience.”

Stephanie is a groundbreaker in holding space for women in architecture, leading research into the consequences of gender disparity in the industry as part of Ankrom Moisan’s 2023 Do Good Be Well research scholarship program. Her collaboration with Amanda Lunger and Elisa Zenk, titled “Where are the Women,” revealed six key challenges faced by women within the industry, and proposed solutions to boost equity and support women in architecture.

Elisa, Amanda, and Stephanie together in the Portland office, from their Do Good Be Well research project feature.

It was that spirited drive and initiative that led to Stephanie being nominated as Ankrom Moisan’s Employee Ownership Champion. When asked what ’employee ownership’ means to her, Stephanie revealed that it means “taking responsibility and ownership not just for your work, but also for your team’s work.”

Making the point that a document set is not created by a single person on their own, but rather by a team of people, Stephanie looks at the bigger picture, seeing how each team member contributes to the greater whole of a project’s design. “It’s important to recognize that it’s all of us together. We need to own that. That’s how I think of employee ownership; what we produce is our work.”

Stephanie’s Employee Owner Champion Nomination Video

Stephanie found out about her acknowledgment when she received a ‘congratulations’ text from Amanda. “I didn’t understand what she was talking about,” Stephanie admits. “Then I saw it on the Insider. I was very flattered and honestly a little bit shocked. I don’t have a project team I’m working with, so I didn’t think that this was something I had a chance of winning. I’m very appreciating of the nice words from everyone who nominated me and recognized the kind of work I’m doing, even if it’s just me doing it right now.”

Once the shock of winning subsided, Stephanie began to think about the future of what the Rewards & Recognition honor could be. “I really hope that this program encourages us to acknowledge when people do a job well done. Having a culture that values employees who do a good job and a program to celebrate that is a good thing that we should keep moving forward,” she shared.

Called out in her nomination video by David Kelley for leading the first ‘Lessons Learned’ with the housing studio, Stephanie stepped up to share what different teams can do to support CA work. The studio wanted to have some informative discussions with groups that weren’t in the same studio, discipline, or practice as them to provide updates on what’s going on in the office. “I put together a list of dos-and-don’ts for construction administration (CA) and other things I found helpful for what I’m doing,” Stephanie said. “I was trying to provide knowledge about what I thought was good and what I thought could be worked on. I think it led to some good conversations, because everybody has their own opinions on the best ways to do certain things. It was a productive work session that I think everyone appreciated, since it was the first of its kind.”

Being able to communicate to different studios how to support the CA work she does was huge for Stephanie. As the only one doing CA for the Shea project she is working on, she has a lot on her plate. She revealed that one way she’s supported in her role is by checking in with Don Sowieja, her direct manager, every other week. “He has a lot of trust in me. It helps me be successful, knowing I can come to him,” she shared. “He provides me with guidance but doesn’t overstep. He allows me to do work that maybe I haven’t done before, but he trusts I can do it well. That’s something I find very supportive – having trust as an employee.”

Outside of work, Stephanie continues spreading support by volunteering for ACE, and Architecture, Construction, and Engineering after-school mentorship program for high school students in the Portland area. “It helps me feel rejuvenated and excited about where architecture is going,” Stephanie said. “It’s fun to see students get excited about what we do. They come up with some very cool designs and ideas, so seeing the next generation really inspires and excites me.”

Stephanie with the ACE group in the materials library at Ankrom Moisan’s Portland office.

Her advice for the next generation of architects and interior designers is simple, yet impactful. “There are no dumb questions,” she said. “When you’re so young and first starting your career out, you think that school prepares you for everything in the real world, but it really doesn’t. It gets your mind ready to absorb all the information that you can’t learn in school.” Stephanie encourages young professionals to ask questions and absorb all the knowledge they’re receiving. “Don’t pretend you know everything right off the bat, because that’s not true,” she emphasized. “Every day I’m learning new things. Be open to always learning more.”

Going back to the idea of employee ownership, Stephanie’s second lesson for young professionals just starting out in their careers is that architecture – at least here at Ankrom Moisan – is a team effort. She emphasized being open to collaboration, saying “It’s not just one person doing everything. I really encourage everybody to have a mindset where they’re working as a team and being a team player.”

Working together as a team means many challenges are overcome quicker, and with less difficulty. That doesn’t mean that there will be no challenges, though. For Stephanie, the biggest challenge she’s faced in her position is leading a team that’s constantly changing. “Trying to keep things moving forward while everything in the background is shifting around you is really difficult,” she said. “To overcome that, being able to rely on other people in the office for guidance was huge. I had to come up with a work plan so that even if my team is changing, I still have a path to move forward.”

Just over the horizon is a new challenge for her, though – motherhood. “I’ll be confronting another big challenge moving forward, which is balancing both motherhood and working. I’m really curious to see how that will work out, moving forward,” Stephanie said. She plans on using her recently earned sabbatical to take an extended maternity leave, adjusting to her new life as a mother before coming back to work. Though this challenge will be one she must face herself, without a team, Stephanie knows that all of Ankrom Moisan is supporting her in her journey through this new stage of life. As the Employee Owner Champion, she knows that she is never truly alone here.

Employee Spotlight: 2024 Q1 HOWNOW Champion James Lucking

Acknowledged in the first wave of Ankrom Moisan’s Rewards & Recognition program winners as a HOWNOW Champion, James Lucking embraces and celebrates AM’s culture, going the extra mile to embody the firm’s HOWs.

James in Ankrom Moisan’s Seattle office.

As a Technical Advocate, James’ primary role is quality control. “The bottom line is that I have to ensure the quality of deliverables when they pass through my hands,” James explained. “The unique thing about the way we do it at Ankrom Moisan is that the other Technical Advocates and I get assigned to a team and go through the entire process with them.” In this sense, James is there every step along the way. “I’ll do review at each milestone,” he elaborated. “I’m also a resource for when people want to ask quick, one-off questions.”

Because of his role as a resource for project teams throughout the design process, James is deeply immersed in the firm’s culture. He knows the ins and outs of each studio and helps to streamline the project design process for each of them. His work spans project types, but his favorite is renovations. “I enjoy working on projects with an existing component as well as new,” he shared. “When we have a project where we’re saving a historic facade and building onto it, those are always interesting to me. The intervention between the new and the old is very interesting to me.”

James’ HOWNOW Champion Recognition banner.

James first came to Ankrom Moisan around a decade ago, enticed by an open position that would ultimately become his. “I saw an opening for a Technical Advocate (TA) role and thought it was a good fit for my personality and the type of experience I had in my career, which has been much more technical than design-oriented,” he said. When he first started, Ankrom Moisan was still operating out of an office in Pioneer Square. “The space was pretty full, and we were growing really fast. It was quite a roaring economy at the time, it was great to experience this super high-energy design firm.”

“It was a highly collaborative environment,” he recalled. “We would have pin-ups around once a week. At other firms, people typically present their work in a general, architectural way. Ankrom Moisan does it differently. People are very directed and focused on what they’re contributing, and always open to suggestions. People would say ‘hey, we’re working on this and have this specific challenge’ and everyone would give ideas. It was a new way of doing things.”

Though James and the rest of Ankrom Moisan worked hard back then, they also embraced our HOWs by having fun with it. “We had a lot of celebrations of milestones. When the team completed some SD or DD milestone, they’d all go out to lunch and invite the TAs on the project,” James said.

Over the course of his career, James’ areas of focus have changed slightly. “I came with a lot of experience in building enclosures and exteriors,” he explained. “I’ve gotten to learn quite a bit about various codes, how they work together, and how to quickly find the right answer to a problem within the code. Sometimes it can be a little challenging.” He’s learned that if you think you’ve found the answer you’re looking for, but haven’t looked in at least two different places, there’s a good chance it’s not right.

Illustrated graph of Ankrom Moisan’s HOWs.

Nominated by Cara Godwin, Associate Principal, Murray Jenkins, Vice President, and David Kelley, Senior Principal, James found out about his recognition as a HOWNOW Champion the day after it was announced on SAM. “I felt really flattered,” he stated. “It felt good to have someone say that they thought I embodied the firm’s values and methods.”

Explaining how he embraces Ankrom Moisan’s HOWs, James said that he doesn’t see any other way to do it than to look at them frequently. “I look at the HOWs and ask myself if one of them will help me bring my best self to the problem I’m facing. They usually help with challenges when you’re struggling with something,” he stated. “To step back for a second and refresh your understanding of the HOWs is kind of like asking ‘what would David Kelley do?'” It helps put things in perspective. In James’ view, adhering to the firm’s HOWs ensures that Ankrom Moisan’s operations run smoothly. “We created the HOWs to try and make our firm really awesome, so if we look at the list and pull the rope in the same direction, so to speak, it helps everyone in the firm.”

James’ HOWNOW Champion nomination video.

The easiest HOW for James to embrace is simply being himself. “Being a technically oriented architect, this role is tailor-made for me,” James shared. “I feel like I can really be myself here, whereas at other firms I haven’t felt that way. The architectural field can be so design-focused that you can feel unworthy if you’re not a creative conceptual designer or architect.”

While he’s been with Ankrom Moisan for over a decade now and a lot has changed since he first started, James claims that the hardest HOW for him to follow is embracing change. “I can tend to resist change when it comes along, he revealed. “I always have to remember that we’ve got a bunch of really talented people here who are very ambitious and that there’s going to be changes that will come out of that, and that’s a positive thing.”

James working with Omar Torres, Chie Yokoyama, and Nancy Kwon (Left to right).

As a TA, James is a member of TAG, the Technical Advocate Group, where he does his best to bring Ankrom Moisan’s HOWs into their daily operations. Within TAG, specifically, James recognizes that there are many advocates for change that help him adjust to and embrace change. “The hard changes for me don’t come from the internal TAG group, because we discuss them and how to get onboard with them,” James explained. Rather, it’s technological changes that are difficult to adapt to. “The second that IT changes something, I have to step back and remind myself ‘this is changing for a reason. Those technological changes have gone through a vetting process and are being made by people who want to make things better.'”

Although it’s the HOW that he finds the most difficult to embrace, James finds his inspiration to embrace change in the people he works with. “There are so many talented people that come up with creative ideas of how to solve various problems and ways to add value to a project that the owner might not have thought of themselves,” James said. “I’m inspired by that every day.”

With the future on his mind, James’ advice for young professionals who may just be starting out in their careers and are looking for ways to embrace HOWs – whether they’re their own HOWs or the firm’s – is to keep learning and never be afraid to ask questions. “You’re not going to know it all,” he imparted. “You can still ask questions no matter how far along in your career you are. Architecture is big and complicated, and it’s always changing. Stay humble and always be ready to ask questions.”

Employee Spotlight: 2024 Q1 Design Champion Filo Canseco

Recently honored as Ankrom Moisan’s first-ever Design Champion through the new AM Rewards & Recognition program, Filo Canseco goes above and beyond, pushing the boundaries of graphic design by putting part of himself into his work.

Filo’s Design Champion Banner.

Filo became interested in design at an early age. Coming from a creative family, he was naturally attracted to anything related to art and design, often taking up the modes of expression shared with him by his relatives. “My uncle Aaron, who is an illustrator, introduced me to graphite and chalk early on in my childhood. Similarly, my aunts embroidered, so I learned embroidery,” Filo shared. It wasn’t until later that he realized why his family were passing on their creative abilities. “They knew that because of our family’s immigrations status at the time, having recently become naturalized citizens, they had missed their opportunity to pursue the arts. I was the only one who had a chance of pursuing design in college and as a career.”

Interested in animation and the process of making illustrations come to life, Filo applied to The Art Institute of Portland after high school. He wasn’t accepted at the time, which was “devastating,” but something he’s glad about now. Despite not immediately applying to a college design program again, Filo pursued his passion for design wherever he could. “I created business cards and websites for friends’ small businesses, designed posters for friends in bands, and later picked up photography and videography,” he said. Though he was immersed in creating unique one-of-a-kind designs for friends, he felt that his lack of technical knowledge meant he didn’t qualify as a true graphic designer. “I designed my entire brand identity in Photoshop without knowing much about Adobe’s software. It wasn’t until a friend suggested I start charging for my design services that I considered this as a potential career.”

Filo saw his opportunity to follow his dream and practice design and took it. When he returned to higher education nine years later, it was confirmation that a career in graphic design was indeed meant for him. Even though he already had some experience under his belt, learning the ins and outs of design in an academic setting changed his perspective on his process. “I was captivated by the fundamentals of graphic design, graphic design history, hand-lettering, pottery, digital graphic design, and all its multifaceted realms,” Filo said. “We learned design, we learned what the great classical artists were thinking and feeling, then we broke down their designs to be put back together with a little piece of ourselves in there. That was huge for me. I didn’t understand it at the time, but now I feel that change in approach is what keeps me producing innovative work.”

Filo at his desk in the Portland office.

When Filo first started at Ankrom Moisan after graduating from Portland State University in 2022, it was during the pandemic, before AM’s offices instated a two day per week in-person requirement. Because of this, Filo only met a handful of people after starting. “I might have seen Juan Conci or Fernando Abba, our Visualization Managers, once or twice,” he recalled. “It was very lonely. There was nobody in the office. Everything was through Teams meetings.”

Looking back, Filo believes that this slow introduction to the world of Ankrom Moisan worked in his favor. “I was fresh and brand new not only to an architecture firm, but also to having a graphic design job. Pandemic distancing and remote work gradually got me into Ankrom Moisan’s firm culture and what my role was.” He feels lucky to have been able to meet people one at a time, as it gave him a better chance to form connections with new coworkers and assimilate to a new industry than if he had met everyone all at once.

Being able to integrate into AM’s work culture at his own pace deeply influenced how Filo takes a project’s design direction and turns it into an effective deliverable that resonates with the company’s culture and wins new projects.

Filo’s design work for the ‘Women Rising’ DEIB campaign

Over the past two years, Filo and his eye for design have grown considerably. He’s grown accustomed to taking the lead on design campaigns, and the responsibility that comes with it, thanks in part to Ankrom Moisan’s unique structure and system of support. “I don’t think I would have grown as fast as I did if Ankrom Moisan’s work culture wasn’t so well established. If I had my first job at a popular downtown design firm, I would have had to go through a lot more hierarchy to get where I am today,” he remarked. “I would have been forced into the box of ‘junior graphic designer,’ and wouldn’t have had the opportunity to grow and realize that I have a lot more capabilities than that.”

Growing into his new capabilities, Filo realized that one of his favorite parts of doing graphic design at Ankrom Moisan is the glowing feedback he often receives after completing a deliverable. “It feels so rewarding to do so much with such a small team,” Filo expressed. “People will come to us and ask what external team we hired, and it’s just like ‘no, we’re just a group of three people taking Ankrom Moisan’s supportive culture and producing this collateral.'” For this reason, the DEIB people-centered campaigns have been a favorite of Filo’s. “These campaigns have really projected me into a space where I can be a graphic designer as well as a creative lead.”

Filo with Emily Lamunyan and Dani Murphy behind the scenes of the AMasterclass DEIB campaign.

When he found out about his recognition as Design Champion, Filo didn’t know how to react. “I didn’t know our president, Dave, would make a video response. I was completely blown away and had to take a moment to really let it sink in,” he said. It was a bit of a surprise. “I found out in a Teams meeting. It was a little awkward finding out and then making my own poster,” he joked. “I guess it had to happen though, since I’m the one doing graphics; there was no way of having somebody else make it.”

Filo’s Design Champion nomination video.

Recognized in his nomination video by President Dave Heater, Vice President Alissa Brandt, Director of Marketing Emily Lamunyan, and Visualization Manager Juan Conci for his willingness to step outside of his comfort zone as well as for his game-changing design work that gives Ankrom Moisan a competitive advantage, Filo shared just how and why his graphic design efforts have had such a big impact on the firm. “Feeling like I can reach out to anyone on the marketing team at any point to get feedback is just golden. I haven’t experienced that with any other job.” Aside from his team’s support, Filo can produce such stellar graphics, putting part of himself into his designs, because of his working process. “My process is about staying curious to ensure the final design is innovative and cutting-edge, not formulaic,” he explained. “I’ve been fortunate to have an innately curious personality. I didn’t realize it until recently, but it’s what helps me out of my comfort zone, allowing me to integrate my lived experience into my designs.”

Filo’s promotional work for the Asian American Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander Heritage Month celebration DEIB campaign.

As one of the first Ankrom Moisan employees to be celebrated through the new Rewards & Recognition program, Filo has high hopes for the future of the program. “I hope and envision that the rewards and recognition program transcends Ankrom Moisan. It’s a great way to show how important and strong our culture is here,” Filo said. “I also hope future champions see the acknowledgement as a milestone and an opportunity to reflect on their career. Being recognized made me step away from work and life and realize how I’ve changed as a professional.”

Reflecting on advice for emerging young professionals in the field of graphic design, Filo had this to offer. “You’ve done the hard work when it comes to learning and educating yourself. Now that you’ve graduated, take it slow. Have fun. I know it sounds cheesy since it’s one of our HOWs, but having fun with what we do is super important to creating balance.” He also emphasized that “making mistakes, as well as connections, is ultimately what helps you get to know your team and everyone else at the firm.”

Taking his Design Champion recognition as a chance to look back at his career, Filo reflected on how everything he learned from his family, high school, gap years, and time at PSU has led him to this moment. “Being a graphic designer has always been my goal, but I now see new opportunities to become much more,” he revealed. “I see myself in a role where I can share my experiences – perhaps as a mentor, a supervisor, or a director. Who knows!” Right now, Filo’s focus is on just enjoying his moment. It’s more than deserved.

Employee Spotlight: Amanda Lunger

Amanda Lunger wears many hats and has lived just as many lives. Recently, she was promoted to the role of Sustainability Advocate. Reflecting on her journey to this new position, Amanda sat down to discuss sustainability, career advice, and how her final studio project at the University of Oregon – a passive house affordable housing project – led to her being recruited to work at Ankrom Moisan.

Amanda outside of Ankrom Moisan’s Portland office.

Q: You were recently promoted to a sustainability role within the practice team. What can you tell me about that?

A: Well, we’ve had different groups in the office before to try and push sustainability initiatives and ensure there is adequate education about the topic, but now we’re taking the extra step of having a dedicated role that’s responsible for setting and executing goals and initiatives related to the sustainability of the firm. In this sense, I work in an overhead capacity to develop internal processes and education opportunities to further our sustainability efforts, and then also support projects as the need arises. It entails helping people set sustainability goals, research different technologies, and assisting with the selection of appropriate sustainability certification programs for projects. Eventually, I’ll assist with business development, telling the story of Ankrom Moisan’s sustainability expertise on our website and in RFPs, helping designers feel prepared to talk to clients about sustainability.

Q: What does sustainability mean to you?

A: I think to me, sustainability is recognizing the interconnectedness of all the decisions that we make as humans and understanding that those decisions have implications for all the other living things on this planet, as well as for future generations and even our future selves. Personally, my values and beliefs around sustainability are inherently tied to my spiritual beliefs, because I believe that all life has intrinsic value and that we have a moral obligation to look out for the wellbeing of all living things on this planet.

Q: What do you hope to accomplish in your new role?

A: I hope to help create and push forward a culture at Ankrom Moisan where sustainability is just part of everything we do. Many different things might have to happen to get us there, but if Ankrom Moisan can be known as a firm with expertise in sustainability, and if our staff can really feel that, then that’s a good sign of success to me.

Luckily, firm leadership has decided that this is the year to really start prioritizing sustainability. I am so excited to be a part of that effort and to help with that push while we have the momentum and support of leadership. It feels like a good time to be stepping into this role.

Q: Aside from sustainability-driven efforts, what is your favorite type of work to do? Why?

A: I really love the work I’ve done here at Ankrom Moisan with our mission-driven nonprofits. Specifically, working on affordable housing with REACH has been very rewarding because I really respect the mission of those clients. What they’re trying to do is better the lives of the people they serve.

I also enjoyed being in more of an overhead support position with the transition to BIM, and now again with my new sustainability role. I’ve realized over the course of my career that I get the greatest fulfillment from helping my coworkers and making their lives easier. I feel very appreciated in those kinds of support roles – they’re what I enjoy most.

Q: How long have you been at Ankrom Moisan?

A: I’m a boomerang employee. Initially, I worked here for two years – from 2013 to 2015 – as an architect, but then left Ankrom Moisan to work at a few other offices. I came back in February of 2019 to work as a BIM specialist because I wanted to make a lateral switch in my career. For this go around, I guess I’ve been here a full five years. I’m entering my sixth year.

Q: What brought you here?

A: This is a fun story. So, I was at the University of Oregon in my final year of the architecture program. I was doing a terminal studio, which encourages students to focus their final project on an area that’s of special interest to them. At the time I had gotten really into sustainability and passive house because of one of my professors, Professor Alison Kwok. I went through a whole intensive passive house training program and got my Certified Passive House Consultant Accreditation (CPHC). For my final studio, I was looking specifically at the applicability of passive house to affordable housing and how mission-driven nonprofits could really benefit from the deep energy savings of passive house, since they’d be able to save money on building operations and funnel those funds back into their programs for clients and the people who live in their buildings. So that’s what I designed. I picked a site in San Francisco and a fake client – a nonprofit affordable housing developer – and I ran an energy model on it, demonstrating how it could meet the passive house standard.

Isaac Johnson ended up being one of my reviewers during my final review. I was really interested in Ankrom Moisan at the time because of the work the firm was doing with affordable housing. Well, after graduation I was working with another firm when I got a call out of the blue from Isaac Johnson. He said something like “Hey, so I remember reviewing your final studio project, and we basically have that project at Ankrom Moisan now. Do you want to come work for us?” He was talking about Orchards at Orenco which is a REACH Development affordable housing project that was pursuing passive house standards, so obviously I said yes. It was really cool coming out of college and working on a project with the exact same sustainability goals that I was passionate about.

Orchards at Orenco.

Q: What was it like when you first started out?

A: We were still on Macadam. It wasn’t the nice office we have now. I remember it felt a little more hodgepodge, but also like there were distinct families within the office. I worked in the basement – there were very few of us down there. We had our own kitchen and conference room; it was like our whole world. It was a very tight-knit group of people because of that. A lot of the young professionals were also recent college graduates like me. It was really nice having that community to commiserate with and co-mentor together.

I was part of two distinct families. There was Jeff Hamilton’s team in the basement, and then there was the recent college graduate family that was spread across different project types. Elisa Zenk and Stephanie Hollar started around the same time I did and were part of that cohort. We became really close friends, along with Elisa’s now-husband who was also part of that cohort. It was a cool way to learn about stuff that was happening across the office, because Elisa would be working on student housing, Tim on something else, and Will on something completely different as well. It made us feel more connected to the firm.

There were also a lot of recreation opportunities. We had a volleyball team; we would play soccer during lunchtime out at the park. It was a great community.

Amanda with Elisa Zenk and Stephanie Hollar on the rooftop of Ankrom Moisan’s Portland office.

Q: Since starting here, how have you grown professionally?

A: My biggest area of growth has been figuring out how to collaborate with other people. You can’t just rely on yourself. You have to work with other people if you want the best results. Knowing your coworkers’ talents and who to reach out to is a very soft skill that nobody really talks about, but I think it’s so critical to the success of the work that we do. As buildings get more complex and we want to use more and more data to inform our designs, having good collaboration becomes all that much more important.

Q: Since you started here, what has the biggest change in the firm or industry been?

A: It has to be the COVID-19 pandemic. That changed the way we work and the way that we collaborate. It also changed the culture of the firm a bit. I think one of the good things that come out of it is that there’s a greater understanding of work-life balance and mental health, and a greater awareness that those things should be prioritized. Sometimes it can feel like the division between work and home doesn’t exist as much, but I think in general, we’re just more flexible about how we work.

Q: What’s your favorite thing about working here?

A: My favorite thing about working at Ankrom Moisan is the people. I’ve found the across the board, in all echelons and experience levels, in all project types and studios, we just have great people. There’s so much support from everyone, not only because of what you can do professionally, but also just because of who you are as an individual. The people I’ve worked with have been excellent coworkers who take a personal interest in you.

Q: What inspires you?

A: It’s definitely nature. I know that sounds cliché, but you won’t find any better designs that what is found in nature. Any system you’re trying to optimize has been done in nature.

My favorite natural space is probably Milo McIver State Park on the Clackamas River. My husband and I are avid disc golfers, which is probably one of the reasons I love that place so much. It’s so lush and green and has such tall trees. There’s also the river there, which is very pretty. It’s so cool to see how the flow of the Clackamas changes seasonally.

Milo McIver State Park throughout the seasons.

Q: What advice do you have for young professionals who are just starting out in their careers?

A: Don’t isolate yourself. Find your tribe. Find your support system of both other young professionals and more experienced people who you can learn from. It makes a huge difference. It helps keep you motivated and wanting to improve yourself. It also helps with mental and emotional health, knowing that you have a support person who you can grab coffee with or step outside to talk about the rough day you’re having.

Get in the habit of taking a personal interest in getting to know your coworkers. Don’t be that person who looks the other direction when you’re walking down the hallway who tries to avoid saying hello. If you’re genuinely interested in your coworkers, it’s a lot easier to pick up the phone and call them about something or send them a random message on Teams. It can even become something that you look forward to if you have coworkers that you enjoy chatting with.

Lastly, I would say, don’t be afraid to ask questions. Nobody is expecting you to be an expert. Take advantage of that by asking questions and learning from people.

By Jack Cochran, Marketing Coordinator

Ankrom Moisan’s Mission and the Emergence of Our Why: Part 1

This is part of a series on the origin of Ankrom Moisan’s mission and vision, our purpose for doing what we do, and the values by which we work. Read Part 2 here.

During the Great Recession work was very slow, and our founder Stewart Ankrom retired. With time and transitional change, we found ourselves looking inward, contemplating our purpose and what makes us unique. Tom Moisan, a founder and the president, held a fall retreat to better determine what we stand for, and where we wanted to go.

This retreat was the beginning of a more than decade-long journey to capture the collective values that make our firm a great place to work. Tom and seven managing principals met over and over to put words on the wall, defining and refining their deeper meanings, especially: “listening”, “learning, and “empowerment’. From these early sessions, a working list of seven values and our mission (our What) emerged:

We design places where people and communities thrive.

Between 2014 – 2017 we saw high growth, and we were using our values and our mission as a touchstone to orient new employees and attract new clientele. During that time Tom Moisan, our second founder retired, and Dave Heater, Managing Principal of the Seattle office, stepped into the role of President. With the fast and furious growth came the realization that Ankrom Moisan needed to relook at the mission and values and see if they truly communicated the vision and direction of the firm.

Around this time President Dave Heater read the book Find Your Why by Simon Sinek; “As I started reading the book, I got so excited because I realized that it was a process that was based on storytelling. And I thought, ‘This is the perfect process for Ankrom Moisan to uncover what is at our core, what is our driving purpose, and what makes us unique in the world.’”

We began the Why process in 2018, with thirty of us participating in a two-day retreat. We were a mix of leaders, designers, marketing, and accounting staff: a large cross section of the firm. The process began with an emphasis on storytelling and each person defining their own personal WHY for their life. Stories illuminated motivation, inspiration, and perseverance. The Why statement is meant to bring awareness to “why we get out of bed to come to Ankrom Moisan each day”. Rich, meaningful, personal stories were revealed throughout the retreat, and everyone left feeling energized and uplifted.

As one of the leaders participating in the retreat, Jennifer Sobieraj Sanin, Managing Design Principal, marvels that, “it’s incredible that a large group of people sharing stories of experiences at the firm were finding commonalities while crafting the Why. Usually, it takes two years to do anything, and this was successful in two days.” The Why we came away with during that retreat was unanimously agreed upon:

Inspire and empower people to explore beyond the expected.

Nandita Kamath, Associate Architect, has been with us for over a decade, and she participated in the larger listening sessions as well as some of the smaller workshops over the years. She adds another benefit of the sharing and storytelling, “It was great to hear others’ experiences about starting at AM, and what was great about coming into the firm. It gave us a chance to reflect on why we are here, doing what we’re doing. It has been an inclusive experience.”

Among the stories told were general themes of coworkers having each other’s backs, shared memes and uplifting messages while facing stressful deadlines. Having a good time, encouraging each other when needed, and being respectful of each other’s lives show that mutual support and camaraderie really stand out as reliable methods of empowering and inspiring each other. Nandita shares that the Why comes up regularly in her day-to-day work, and though it can be tough to put into practice, mentorship is a great example of putting the Why into play, as the benefits of mentorship, ideally, can go both ways. It is an ongoing opportunity to have an introspective look at how we operate.

Jennifer says that to inspire and empower as a leader is more top-of-mind, and that it’s about making sure you play to people’s strengths, ensuring that they are in a place to succeed, and finding ways to remove obstacles for more confidence and autonomy as needed. And on the client-facing side of things, “it’s often about encouraging your clients to not ‘rinse and repeat’. Let’s try something new, a little different, out of the box.”

Our Why continues to resonate, and is present in our everyday work, while interacting with our clients and our coworkers. We are pushed to go further and be better by living by the mission and the Why we have defined for ourselves.

by Kerstyn Smith Olson, Content Coordinator

Getting Involved in the Interior Design Industry

Three members of our interiors department, Roberta Pennington, Clare Goddard and Jessica Kirshner, discuss their experience with the International Interior Design Association (IIDA) and how their involvement in the organization has propelled their professional careers.

Left to right: Jessica Kirshner, Maddy Gorman, Clare Goddard, Roberta Pennington, and Jenna Mogstad at an IIDA event

Q: What’s your experience with IIDA? How were you involved?

Roberta: I have been an IIDA member since graduating (the second time) in 2001. My first event was an awards breakfast at the Governor Hotel in PDX also in 2001; I didn’t know anyone, but the Members were super friendly and welcoming.

I attended MANY events consequently then stepped up my volunteer time to the Board in 2009. I dove into the President Elect role during a time when Members, including myself, did not have jobs. IIDA gave me the stability and connection I was missing during the year I was unemployed.

After my Presidency, I stayed on as a Chapter Advisor and most recently came back to serve on the Board with the Advocacy team. I’ve been involved in one way or another with finding legal recognition for commercial interior design in Oregon since 2003, and I want to continue to be a part of the momentum gaining speed nationally. It’s an exciting time for interior designers on the legal front.

Clare: I have been involved on the board for a little under 5 years (started October of 2018) first as the VP of Communications and then moved into President-Elect/President/Past President roles.

Jessica: I started with IIDA in college, I was on the student board as the fundraising chair. Once I graduated and was hired on full time at AM, I joined the Oregon Chapter Board as the Director of Social Media and I have held this position for the past 2 years.

Q: How did membership in IIDA benefit you professionally?

Roberta: Networking! I can go anywhere locally and nationally, and a complete network of design leaders are available to tap.

I became much more active during the Recession in 2009 when I stepped up to be President-Elect. The network of people on the Board were instrumental in getting my name to the top of a list of persons to hire when firms were not hiring. I’m very grateful to this group.

I also got to know women in the profession who were and still are my mentors and friends. Their experiences showed me having a child does not mean the end of my career. Women don’t have to “act like a man” to be taken serious. Speaking my mind does not make me a “bitch.” AND: I’m a very entertaining public speaker. Very liberating.

Clare: Prior to joining the board (and when I was in San Diego), I credit IIDA with connecting me to potential employers and creating a sense of community in a city where I knew no one. Joining the board here in Oregon has greatly improved my leadership and delegation skills. It has also helped me to create a sense of community here in Portland, beyond AM. I consider it a privilege to have served this design community on the board in helping to be the face of interior design for the state of Oregon. Being part of the board, in any capacity, is how I give back to the profession that I am so passionate about.

Jessica: I have been able to attend countless events that have both inspired me and helped me professionally. These ranged from forums to socials. Each event hitting on a different and important topic in our industry. It has also been a great networking opportunity that has allowed me to connect with people I wouldn’t have met otherwise.

Q: What’s your most memorable moment from your time in IIDA?

Roberta: A standing ovation at the Annual Celebration 2010 at Ziba. I delivered my incoming President speech. I wasn’t sure I was coming in with the right message; that being “We’re not dead; we will get thru this Recession somehow.” When the room of people stood up, clapped, and cheered, I knew I was going to be okay. The CEO of IIDA National was there and told me she would never go on after me again. A real head-swelling moment.

Clare: That has to be the CLCs (Chapter Leaders Conferences) held in Chicago and regionally. I love getting to connect with leaders from other chapters across the US! It was amazing to learn from others and to make new friends. The CLCs will be what I miss the most post-presidency.

Jessica: I don’t necessarily have a specific moment but getting to serve on board with such amazing people has been so motivating. It’s helped me to grow in so many ways. I’m so thankful to have been on the board.

Q: How did AM support your involvement?

Roberta: In my Board involvement, AM has reimbursed annual dues as well as allocated time for volunteering. My current role as VP of Advocacy means I’m spending time meeting with committees, legislators, consultants, and peers often. I can keep my PTO for actual vacation time.

AM has also been an annual sponsor to the Chapter every year an employee has served on the Board. That sponsorship is instrumental in keeping the Chapter going.

Leadership has also written letters to legislators during recent pushes for legal recognition of interior design. This small act shows the value AM places on my education, experience, the NCIDQ, and what I bring to the table as a commercial interior designer.

Clare: AM is one of the more supportive firms in the state. They not only encourage employees to be on the board, but back up that support by paying for IIDA membership and providing 2 paid hours per week for board tasks for those serving on the board. I count myself very lucky to have such a supportive firm.

Also, I think because of that support, Ankrom has had consistently the highest number of people serving on the board (this past year, there were five AM’ers on the board). We always joke that House Ankrom is taking over. Additionally, not only has AM supported individual board members, but they have also lent us the office for multiple board retreats and board events.

Jessica: AM was completely supportive throughout my time on the board, as well as everyone else in the interiors department who was on the board. The interiors leadership team encouraged us to attend IIDA meetings and events and would even show up to events in support.