Our in-house sustainability expert, Amanda Lunger, participated in the 2025 International Mass Timber Conference this month.

Amanda attended several sessions to better understand the benefits of Mass Timber—beyond sustainability—for developers and building owners.

Here are four key insights.

Mass timber creates opportunities for rental premiums.

One developer shared that in their spec-built office building, there was a 20% upfront cost premium for mass timber over light gauge steel, but their building commanded a 40% rental premium when compared to other conventional structures in the area!

Mass timber results in cost-savings.

Although the base material cost of wood is currently high, savings from shorter project timelines, reduced onsite labor, lower import duties, and other operational efficiencies can offset the initial premium. Plus, mass timber performs better thermally, further enhancing its long-term cost-effectiveness.

Mass timber is a long-term investment.

Mass timber structures are valuable long-term investments thanks to their adaptability. CLT panels are easily cut into and filled in, making mass timber structures flexible to the changing needs of a building program and ideal for tenant improvement projects. Mass timber structures are also often inherently designed for disassembly, meaning they can likely be deconstructed and reconstructed in another place in the community when densification happens.

Mass timber requires design team expertise.

The first question an insurance company will ask is whether the design and construction team has any experience with this typology. It’s critical to have an architect who understands the specific moisture, fire, and building code concerns that come with wood buildings.

Mass Timber Case Study: Sandy Pine

As a firm, Ankrom Moisan has a robust experience with mass timber. We were early adopters of the technology, and our expertise exemplifies our commitment to both sustainability and innovation.

Initially, we carved out a niche in mass timber office buildings, completing several projects with technologies like CLT, NLT, and Mass Plywood systems.

As our expertise and relationships in the mass timber market grew, we decided to merge this knowledge with our core strength in multifamily housing. With over 33,000 residential units completed for developers over the past 40+ years, we have amassed a deep understanding of this typology.

Seeing an opportunity for technology to meet typology, we decided it was time to unify and evolve these two distinct areas of expertise.

Sandy Pine stands as a testament to this evolution – a towering high-rise of market-rate housing in Portland, Oregon’s vibrant east side. This project represents many of our best strategies for integrating modular CLT mass timber systems within multifamily buildings, offering a perfect case study for the future of mass timber in housing projects of various types.

Check out the case study here:

The Ins and Outs of Adaptive Reuse

What is Adaptive Reuse?

Adaptive Reuse Residential Conversions are projects that repurpose existing buildings for uses other than what the space was originally designed for.

Adaptive reuse offers developers the unique opportunity to save their investment, create and unparalleled story for end users, and make money by converting a disused or underutilized project into a one-of-a-kind residential space.

Chown Pella Lofts, an old factory warehouse converted into a multi-story residential condominium in Portland, OR’s Pearl District.

However, updating old buildings comes with layers of complexity.

Since 1994, Ankrom Moisan has been involved with adaptive reuse projects and housing conversions. The depth of our expertise means we have an intimate understanding of the limits and parameters of any given site – we know what it takes to transform an underperforming asset into a successful residential project.

Why Conversions?

There are many reasons to choose conversion over construction when considering how to revitalize old structures or adapt unused sites.

Rental Housing Demands

According to the National Association for Industrial and Office Parks (NAOIP), the United States needs to build 4.3 million more apartments by 2035 to meet the demand for rental housing. This includes 600,000 units (total) to fill the shortage from underbidding after the 2008 financial crisis. Adaptive reuse residential conversions are an affordable and effective way to create more housing and fulfill that need.

Desirable Neighborhoods

The way we see it, the success of our buildings, neighborhoods, and infrastructure is our legacy for decades to come. Areas with a diverse mix of older and newer buildings create neighborhoods with better economic performances than their more homogeneous counterparts. By preserving and protecting existing structures, conversions contribute positively to the health and desirability of the neighborhood, leading to a quicker tenant fill.

Being committed to the places we occupy, live in, and care about is another reason to embrace adaptive reuse residential conversion projects; they revive our cities. Reducing the number of buildings that sit empty in urban areas plays a major role in activating downtown districts.

Reduced Waste

Saving older, historic buildings also prevents materials from entering the waste stream and protects the tons of embodied carbon spent during the initial construction. AIA research has shown that building reuse avoids “50-75% of the embodied carbon emissions that would be generated by a new building.”

New Marketing Opportunities

Aside from these benefits to the community, adaptive reuse conversions present a way for developers to recover underutilized projects and break into top markets like affordable, market-rate, and student housing.

Construction Efficiencies

Compared to new buildings, residential conversion projects save time, money, and energy, since their designs are based on an existing structure. Adaptive reuse conversions also benefit from not having their percentage of glazing or amount of parking limited by current codes, since they’re already established.

One-of-a-Kind Design

We don’t believe in a magic formula or a linear “one-size-fits-all” approach to composition. Each site is a unique opportunity to establish a one-of-a-kind project identity that’s tied to its history and surroundings.

At the outset of any conversion, we analyze each individual site and tailor our process to align with the existing elements that make it unique. Working with what you have, our designs and deliverables – plans, units, systems narratives, pricing, and jurisdictional incentives – are custom-fit.

It’s our philosophy that you shouldn’t fight your existing structure to get a conversion made; if you can’t fix it, feature it.

Chown Pella Lofts.

Approaching each conversion opportunity with this mindset, we analyze the factors that set a site apart, and embrace those unique elements to ensure a residential conversion stands out. With this intricate and involved process, we’ve been able to get over 30 one-of-a-kind residential conversion projects under our belt.

Through these past experiences, we have identified six key characteristics that make a project a candidate for successful conversion, and six challenges that may crop up during the renovation process. To learn more about what attributes to look out for and what traits to be weary of when considering a residential conversion, read about our “Rule of Six” here.

By Jennifer Sobieraj Sanin, Design Director of Housing and Senior Principal, and Jack Cochran, Marketing Coordinator.

Residential Conversion Case Study

Converted from a Holiday Inn hotel to a residential apartment complex, 728 16th St. embraces its midcentury hotel past while providing a new take on residential housing. By utilizing strategic efficiencies within the renovation process, Ankrom Moisan’s adaptive reuse and renovations design team contained costs, expedited construction, and completed the project in a sustainable fashion.

The Challenge

Originally constructed in the 1970s, the site of 728 16th St. had seen better days. Years of water damage to the roof and walls meant the building’s enclosure needed updating. Additionally, because the structure was originally designed for traveling guests, rather than as permanent lodging, many of the rooms lacked the necessary amenities for residential living, such as kitchen appliances and other utilities like washers and dryers.

Adding these appliances to the space uncovered unique challenges around the inclusion of proper ducts and plumbing for those utilities.

Before: 728 16th St. as a Holiday Inn

The Solution

Leveraging as much of the pre-existing space as possible resulted in the renovated 728 16th St. building’s unified design. Existing structure, utilities, and MEP infrastructure were optimized by the design team to maximize efficiencies and eliminate the need for a complete tear down. In this sense, the name of the game was understanding the parameters of the site and knowing how to work within those parameters to bring the design intent for the new building type to life.

Since the building’s enclosure was updated during the renovation, the design team was given the opportunity to reskin the building with a high performance rain screen system during the update, preventing any further water damage to the structure. This also allowed the team to shift the site’s layout and the location of amenities; the lobby itself was relocated, moved to a more central location of the site.

To increase the total number of units, portions of the existing hotel, such as the parking lot and food service kitchen were infilled and connected to the new lobby. Other existing hotel rooms were combined to create one or two-bedroom apartment units, with an emphasis on maintaining the pre-established bathroom layouts, since they contained plumbing fixtures and pipes that would be too difficult to relocate.

During: A rendering showing what 728 16th St. might look like as a residential housing complex.

Addressing the challenges that were uncovered by the lack of plumbing, pipes, and appliance ducts in the individual new and existing units, the renovations team made large-scale adjustments to the height of the ceilings, to accommodate those appliance ducts and plumbing pipes.

The Impact

By maintaining as much of the original structure as possible and eliminating the need for a tear down, 728 16th St.’s renovation created an expedited development process that ended up being more sustainable than a new build.

After: 728 16th St., converted from a Holiday Inn hotel to residential housing.

Embracing the existing structure, room layouts, and utilities of the Holiday Inn, Ankrom Moisan’s renovations team turned the underutilized hotel space into an affordable-by-design residential project in a desirable area. Shifting the layout and positioning of the site itself allowed 129 new units to be built, both increasing the amount of available housing in the area and diversifying the unit types within 728 16th St., as the original design was repetitive.

The fresh perspective on modern residential housing brought to life by the Ankrom Moisan adaptive reuse conversion team sets 728 16th St. apart as a place that remains competitive in new markets.

Overall, the building type conversion for this project was successful because the site exhibited at least two of the six key characteristics for effective renovations, otherwise known as the “Rule of Six.” Being situated in a walkable location and having at least a 12,000 square foot plate set 728 16th St. up for success, but a prospective adaptive reuse conversion truly only needs one of the six key characteristics to be a qualified candidate for successful conversion. Read more about the Rule of Six and how to tell if your site would make for a successful residential conversion here.

For guidance through the adaptive reuse process, contact Jennifer Sobieraj Sanin, Housing Studio Design Director and residential conversion expert.

By Jennifer Sobieraj Sanin, Housing Studio Design Director.

Contact: +1 (206)-576-1600 | jennifers@ankrommoisan.com

Should Your Building Become Housing? Critical Considerations for Adaptive Reuse

It’s the question on every developer’s mind right now. Is adaptive reuse feasible for my building? Cost-effective? What will a housing conversion project entail?

Since 1994, Ankrom Moisan has been involved with adaptive reuse projects and housing conversions. The depth of our expertise means we have an intimate understanding of the limits and parameters of any given site – we know what it takes to transform an underperforming asset into a successful residential project.

For customized guidance through the adaptive reuse evaluation process, contact Jennifer Sobieraj Sanin, Housing Studio Design Director and residential conversion expert.

The Rule of Six

While there is no magic formula or linear ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to conversions, we have a framework that should be considered when approaching an adaptive reuse project. We call it “The Rule of Six.”

The Rule of Six outlines six key characteristics that make a project a candidate for successful conversion, and six challenges to be prepared for during the renovation process.

With this informed process, we’ve been able to get over 30 one-of-a-kind residential conversion projects under our belt.

The Six Key Characteristics for a Successful Conversion

Not every building is a good candidate for conversion. By evaluating multiple structure types and working closely with contractors on successful projects, we’ve identified six key characteristics that lead to the creation of successful, low-cost, conversions.

If a property has any of these traits – whether it’s one characteristic of all six – it might qualify as a candidate for a successful conversion.

- Class B or C Office

- 5-6 Levels, or 240′ Tall

- Envelope Operable Windows Preferred

- Walkable Location

- 12,000 Sq. Ft. Plate Minimum

- Depth to Core Not to Exceed 45′

To find out if a property makes for a good adaptive reuse project, consider conducting a feasibility study on the site.

Reach out to get started on your feasibility study today.

The Six Challenges to be Prepared For

West Coast conversions can be particularly challenging with their seismic requirements, energy codes, and jurisdictional challenges – your conversion team should be prepared for these hurdles. The solutions vary by project; contact us to see how we can solve your project’s challenges.

- Change of Use: It’s the reason we upgrade everything. The simple act of changing a building’s use from office to residential immediately triggers a ‘substantial alteration.’ This label starts all the other necessary upgrades.

- Seismic-structural Upgrades: Buildings on the West Coast must meet a certain code level to be deemed acceptable for the health, safety, and welfare of end-users. Often, this required level does not match the current code, meaning negotiations with the jurisdiction are necessary.

- Egress Stairs: Stair width is usually within the code demands for conversion candidates, but placement is what we need to evaluate. When converting to residential, it’s sometimes necessary to add a stair to the end of a corridor.

- Envelope Upgrades and Operable Windows: West Coast energy codes require negotiated upgrades with jurisdictions, as existing envelopes usually don’t meet the current codes’ energy and performance standards. Operable windows are a separate consideration. They are not needed for fresh air but are often desired by residents for their comfort.

- Systems and Services Upgrades: These upgrades often deal with mechanical and plumbing – checking main lines and infrastructure, decentralizing the system, and adding additional plumbing fixtures throughout the building to support residential housing uses.

- Rents and Financials: Determining how to compete with new build residential offerings is huge. At present, conversions cost about as much as a new build. Our job is to solve this dilemma through efficient and thoughtful design, but we need development partners to be on the same page as us, knowing where to focus to make it work.

At the outset of any conversion, we analyze each individual site and tailor our process to align with the existing elements that make it unique. Working with what you have, our designs and deliverables – plans, units, systems narratives, pricing, and jurisdictional incentives – are custom-fit.

To better understand if adaptive reuse is right for your building, get in touch with us. We can guide you through the feasibility study process.

To see how we’ve successfully converted other buildings into housing, take a look at our ‘retro residential conversion’ case study.

By Jennifer Sobieraj Sanin, Housing Studio Design Director.

Contact: +1 (206)-576-1600 | jennifers@ankrommoisan.com

Biophilic Design in Healthcare Spaces

Biophilic elements have numerous positive health benefits for those who use and inhabit a space, as human connection to nature is inherent. The real, tangible impacts of exposure to natural, biophilic elements range from improved mood and quality of sleep, to increased mental abilities and energy levels, among other benefits.

Knowing the myriad of health benefits that being surrounded by nature provides, it’s easy to picture the positive impact of incorporating biophilia into healthcare spaces for both patients and providers. For medical spaces especially, the subtle sense of calmness caused by biophilic design means that check-ups and procedures, that may ordinarily be a source of stress or anxiety to some, are much easier for those patients to handle. From this perspective, using an evidence-based approach to wholistic care means the inclusion of natural, biophilic elements in project designs.

Looking at the intricacies of biophilia, we aim to dive deeper into how the Ankrom Moisan healthcare team utilizes biophilic design to support patients, providers, and visitors in healing spaces.

Healthcare Project Examples

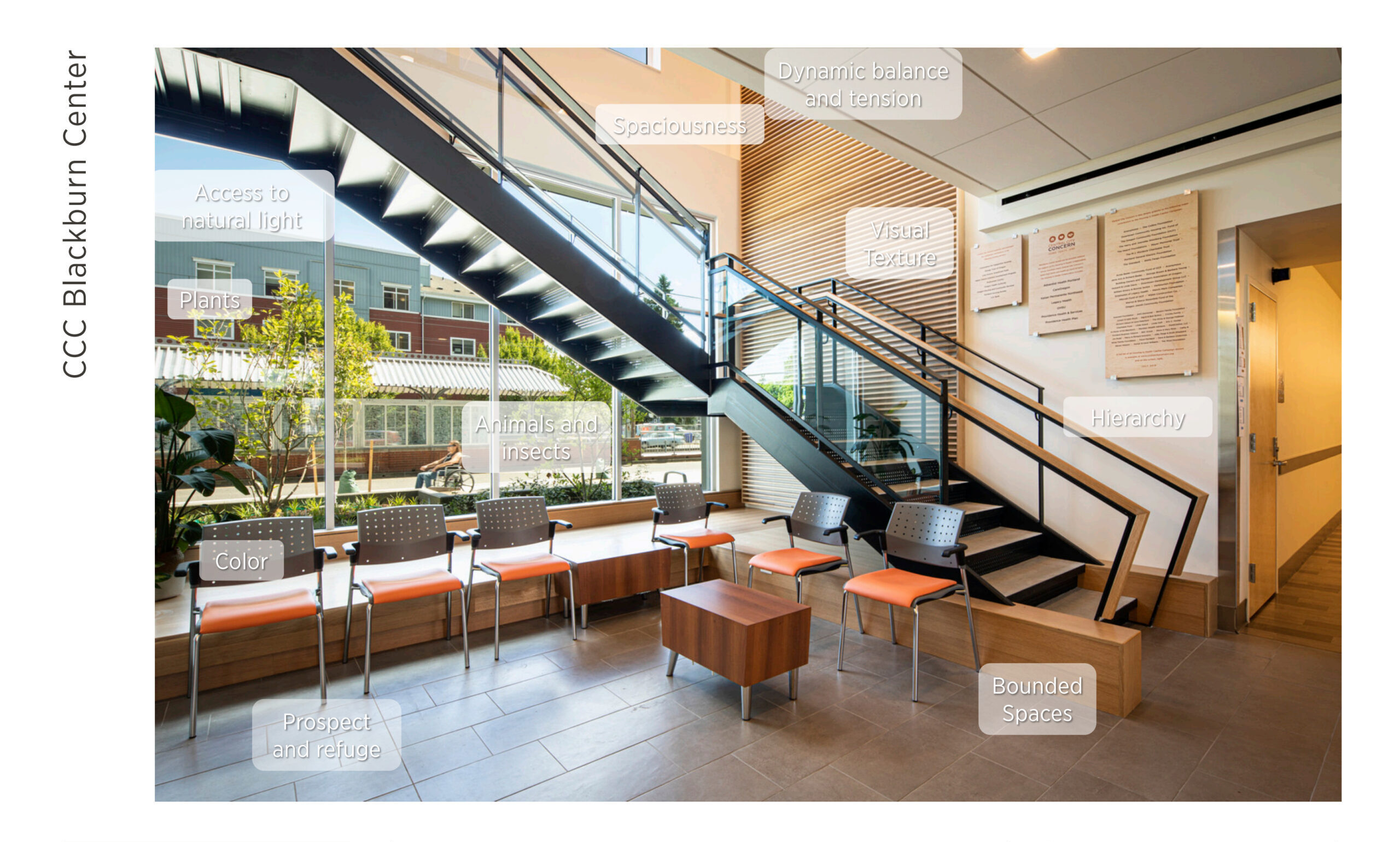

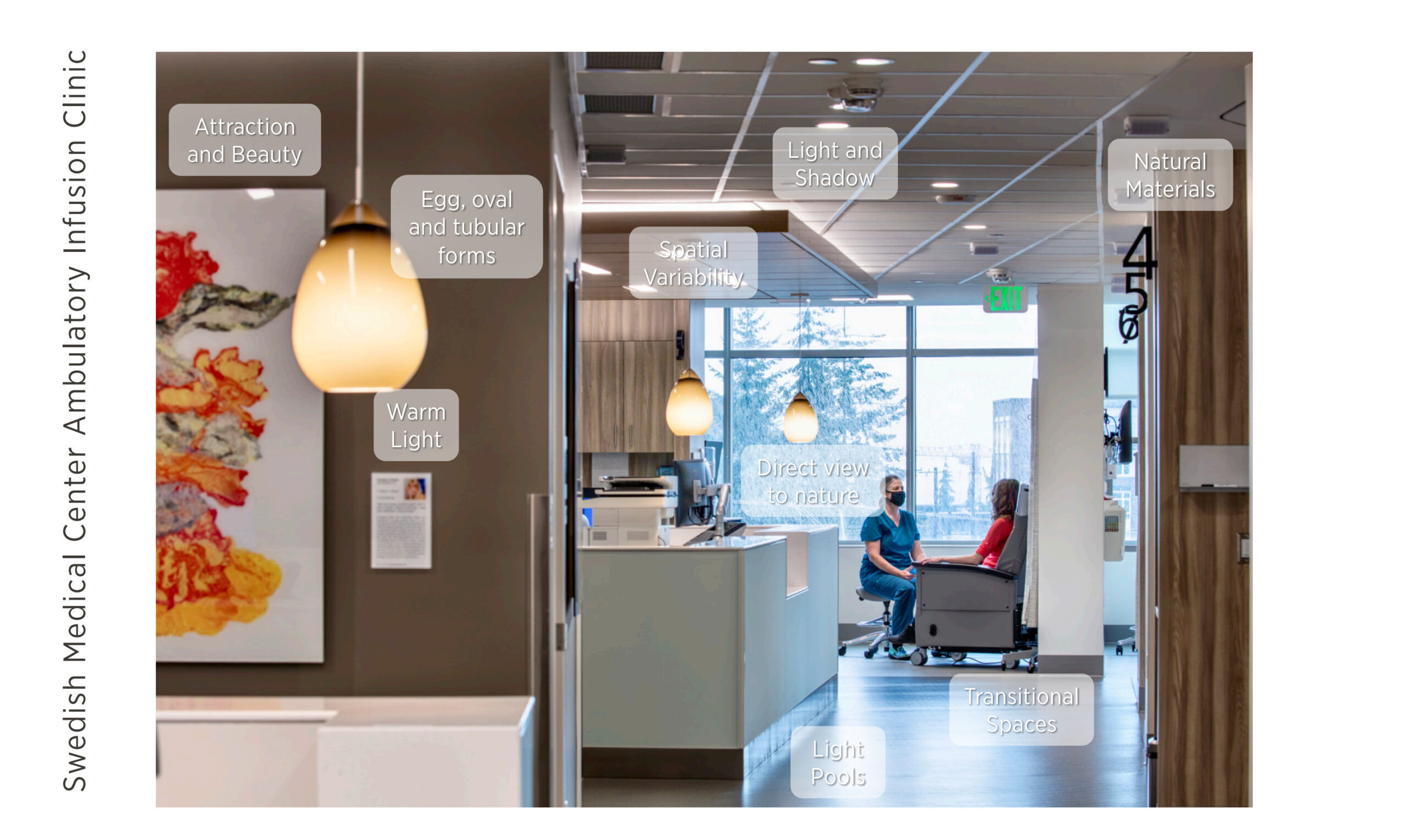

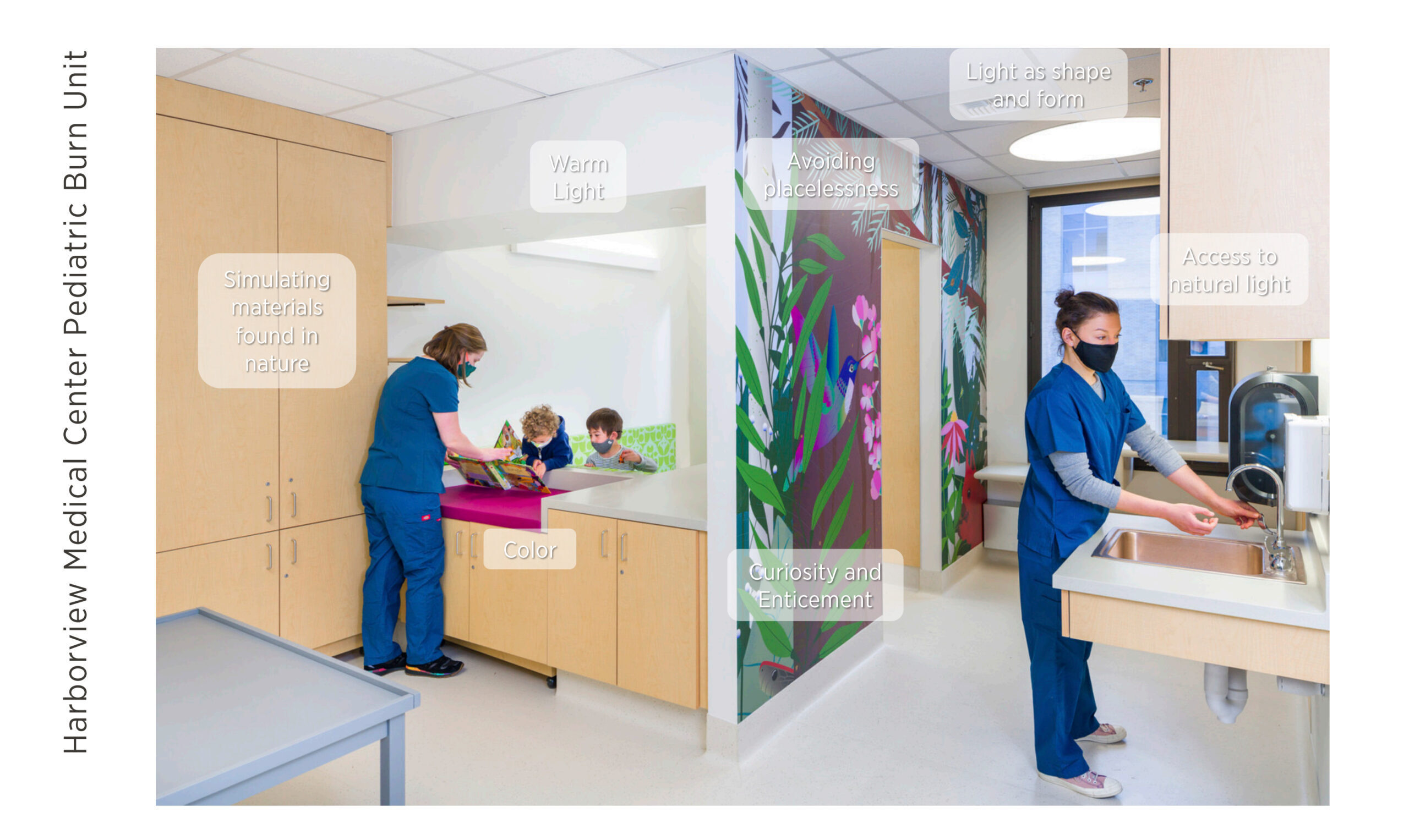

Some examples of how biophilic designs are integrated into healthcare spaces to improve and enhance the patient experience can be seen below, in projects like CCC Blackburn, the Swedish Medical Center Ambulatory Infusion Clinic, and the Harborview Medical Center Pediatric Burn Unit.

CCC Blackburn‘s use of color, texture, and space establishes a dynamic balance of tension and openness within its walls, leading to a combination of both open space and boundaries that emulates the harmony of woodland clearings and fallen trees in the wild. The building was pulled apart to allow natural light into the long hallways and corridors, expelling darkness. Wide, operable windows provide access to sunlight, fresh air, and open space at every level. Views of plants, animals, and insects affirm to patients that they are connected to the outdoors, preventing the feeling of being isolated or stuck in a sterile, empty environment that can be so common in medical spaces.

Similarly, the Swedish Medical Center Ambulatory Infusion Clinic utilizes natural materials, spacial variability, direct views to exterior natural elements, and the intentional use of both indoor and natural light to emphasize the subtle feelings of attraction and appreciation for beauty that results from biophilic design. These features also provide patients with a comforting atmosphere while undergoing treatment, so that even the building’s design around the patient is there to ease pain and reduce discomfort.

The Harborview Medical Center Pediatric Burn Unit also includes biophilic elements designed to help put patients at ease. Wall graphics that reference the outdoors bring color, curiosity, and excitement to the room while simultaneously avoiding placelessness by giving the space its own unique look, feel, and identity. Wood-look and other organic aesthetics combine with natural and artificial light to engage patients, ensuring that they are stimulated while waiting for and receiving care.

Projects that embrace biophilia and include natural features in their design have the additional potential to heal the Earth while healing individuals. This happens foremost through the restoration of natural spaces in and outside of project sites. By including natural features and views, projects often facilitate and encourage the growth of plant life, improving air quality, offsetting a site’s carbon footprint, and contributing to prosperity of the local ecosystem. This is commonly seen with the introduction of native plants and other species that attract pollinators, allowing them to reproduce and continue the circle of life.

We also know that biophilic design has benefits that go beyond pleasant visuals and feeling connected to one’s surroundings. Findings have shown that biophilia boosts immune health, supports mental and emotional health, and can even aid physical recover. Knowing this, designing healthcare spaces to include biophilic connections is a no-brainer.

Resources to Learn More

This only scratches the surface of the conversation around what biophilia is, its benefits, how it can be integrated into project designs, and why it is important. There are lots of materials out there to continue to learn more about this topic.

The resources used to develop the content shared in this blog include The Nature Fix by Florence Williams, Nature Inside by Bill Browning and Catherine O. Ryan, and “14 Patterns of Biophilic Design” by New York environmental consulting firm Terrapin Bright Green.

By Christie Thorpe, Interior Designer, and Jack Cochran, Marketing Coordinator.

Employee Spotlight: Amanda Lunger

Amanda Lunger wears many hats and has lived just as many lives. Recently, she was promoted to the role of Sustainability Advocate. Reflecting on her journey to this new position, Amanda sat down to discuss sustainability, career advice, and how her final studio project at the University of Oregon – a passive house affordable housing project – led to her being recruited to work at Ankrom Moisan.

Amanda outside of Ankrom Moisan’s Portland office.

Q: You were recently promoted to a sustainability role within the practice team. What can you tell me about that?

A: Well, we’ve had different groups in the office before to try and push sustainability initiatives and ensure there is adequate education about the topic, but now we’re taking the extra step of having a dedicated role that’s responsible for setting and executing goals and initiatives related to the sustainability of the firm. In this sense, I work in an overhead capacity to develop internal processes and education opportunities to further our sustainability efforts, and then also support projects as the need arises. It entails helping people set sustainability goals, research different technologies, and assisting with the selection of appropriate sustainability certification programs for projects. Eventually, I’ll assist with business development, telling the story of Ankrom Moisan’s sustainability expertise on our website and in RFPs, helping designers feel prepared to talk to clients about sustainability.

Q: What does sustainability mean to you?

A: I think to me, sustainability is recognizing the interconnectedness of all the decisions that we make as humans and understanding that those decisions have implications for all the other living things on this planet, as well as for future generations and even our future selves. Personally, my values and beliefs around sustainability are inherently tied to my spiritual beliefs, because I believe that all life has intrinsic value and that we have a moral obligation to look out for the wellbeing of all living things on this planet.

Q: What do you hope to accomplish in your new role?

A: I hope to help create and push forward a culture at Ankrom Moisan where sustainability is just part of everything we do. Many different things might have to happen to get us there, but if Ankrom Moisan can be known as a firm with expertise in sustainability, and if our staff can really feel that, then that’s a good sign of success to me.

Luckily, firm leadership has decided that this is the year to really start prioritizing sustainability. I am so excited to be a part of that effort and to help with that push while we have the momentum and support of leadership. It feels like a good time to be stepping into this role.

Q: Aside from sustainability-driven efforts, what is your favorite type of work to do? Why?

A: I really love the work I’ve done here at Ankrom Moisan with our mission-driven nonprofits. Specifically, working on affordable housing with REACH has been very rewarding because I really respect the mission of those clients. What they’re trying to do is better the lives of the people they serve.

I also enjoyed being in more of an overhead support position with the transition to BIM, and now again with my new sustainability role. I’ve realized over the course of my career that I get the greatest fulfillment from helping my coworkers and making their lives easier. I feel very appreciated in those kinds of support roles – they’re what I enjoy most.

Q: How long have you been at Ankrom Moisan?

A: I’m a boomerang employee. Initially, I worked here for two years – from 2013 to 2015 – as an architect, but then left Ankrom Moisan to work at a few other offices. I came back in February of 2019 to work as a BIM specialist because I wanted to make a lateral switch in my career. For this go around, I guess I’ve been here a full five years. I’m entering my sixth year.

Q: What brought you here?

A: This is a fun story. So, I was at the University of Oregon in my final year of the architecture program. I was doing a terminal studio, which encourages students to focus their final project on an area that’s of special interest to them. At the time I had gotten really into sustainability and passive house because of one of my professors, Professor Alison Kwok. I went through a whole intensive passive house training program and got my Certified Passive House Consultant Accreditation (CPHC). For my final studio, I was looking specifically at the applicability of passive house to affordable housing and how mission-driven nonprofits could really benefit from the deep energy savings of passive house, since they’d be able to save money on building operations and funnel those funds back into their programs for clients and the people who live in their buildings. So that’s what I designed. I picked a site in San Francisco and a fake client – a nonprofit affordable housing developer – and I ran an energy model on it, demonstrating how it could meet the passive house standard.

Isaac Johnson ended up being one of my reviewers during my final review. I was really interested in Ankrom Moisan at the time because of the work the firm was doing with affordable housing. Well, after graduation I was working with another firm when I got a call out of the blue from Isaac Johnson. He said something like “Hey, so I remember reviewing your final studio project, and we basically have that project at Ankrom Moisan now. Do you want to come work for us?” He was talking about Orchards at Orenco which is a REACH Development affordable housing project that was pursuing passive house standards, so obviously I said yes. It was really cool coming out of college and working on a project with the exact same sustainability goals that I was passionate about.

Orchards at Orenco.

Q: What was it like when you first started out?

A: We were still on Macadam. It wasn’t the nice office we have now. I remember it felt a little more hodgepodge, but also like there were distinct families within the office. I worked in the basement – there were very few of us down there. We had our own kitchen and conference room; it was like our whole world. It was a very tight-knit group of people because of that. A lot of the young professionals were also recent college graduates like me. It was really nice having that community to commiserate with and co-mentor together.

I was part of two distinct families. There was Jeff Hamilton’s team in the basement, and then there was the recent college graduate family that was spread across different project types. Elisa Zenk and Stephanie Hollar started around the same time I did and were part of that cohort. We became really close friends, along with Elisa’s now-husband who was also part of that cohort. It was a cool way to learn about stuff that was happening across the office, because Elisa would be working on student housing, Tim on something else, and Will on something completely different as well. It made us feel more connected to the firm.

There were also a lot of recreation opportunities. We had a volleyball team; we would play soccer during lunchtime out at the park. It was a great community.

Amanda with Elisa Zenk and Stephanie Hollar on the rooftop of Ankrom Moisan’s Portland office.

Q: Since starting here, how have you grown professionally?

A: My biggest area of growth has been figuring out how to collaborate with other people. You can’t just rely on yourself. You have to work with other people if you want the best results. Knowing your coworkers’ talents and who to reach out to is a very soft skill that nobody really talks about, but I think it’s so critical to the success of the work that we do. As buildings get more complex and we want to use more and more data to inform our designs, having good collaboration becomes all that much more important.

Q: Since you started here, what has the biggest change in the firm or industry been?

A: It has to be the COVID-19 pandemic. That changed the way we work and the way that we collaborate. It also changed the culture of the firm a bit. I think one of the good things that come out of it is that there’s a greater understanding of work-life balance and mental health, and a greater awareness that those things should be prioritized. Sometimes it can feel like the division between work and home doesn’t exist as much, but I think in general, we’re just more flexible about how we work.

Q: What’s your favorite thing about working here?

A: My favorite thing about working at Ankrom Moisan is the people. I’ve found the across the board, in all echelons and experience levels, in all project types and studios, we just have great people. There’s so much support from everyone, not only because of what you can do professionally, but also just because of who you are as an individual. The people I’ve worked with have been excellent coworkers who take a personal interest in you.

Q: What inspires you?

A: It’s definitely nature. I know that sounds cliché, but you won’t find any better designs that what is found in nature. Any system you’re trying to optimize has been done in nature.

My favorite natural space is probably Milo McIver State Park on the Clackamas River. My husband and I are avid disc golfers, which is probably one of the reasons I love that place so much. It’s so lush and green and has such tall trees. There’s also the river there, which is very pretty. It’s so cool to see how the flow of the Clackamas changes seasonally.

Milo McIver State Park throughout the seasons.

Q: What advice do you have for young professionals who are just starting out in their careers?

A: Don’t isolate yourself. Find your tribe. Find your support system of both other young professionals and more experienced people who you can learn from. It makes a huge difference. It helps keep you motivated and wanting to improve yourself. It also helps with mental and emotional health, knowing that you have a support person who you can grab coffee with or step outside to talk about the rough day you’re having.

Get in the habit of taking a personal interest in getting to know your coworkers. Don’t be that person who looks the other direction when you’re walking down the hallway who tries to avoid saying hello. If you’re genuinely interested in your coworkers, it’s a lot easier to pick up the phone and call them about something or send them a random message on Teams. It can even become something that you look forward to if you have coworkers that you enjoy chatting with.

Lastly, I would say, don’t be afraid to ask questions. Nobody is expecting you to be an expert. Take advantage of that by asking questions and learning from people.

By Jack Cochran, Marketing Coordinator

What You Need to Know About Biophilic Design

Biophilia is the concept that there is an innate connection between humans and nature. Our love of nature and tendency to crave connections with the natural world is a deeply engrained and intuitive aspect of both human psychology and physiology. It’s part of our DNA.

Building off that concept, biophilic design is the intentional use of design elements that emulate sensations, features, and phenomena found in nature with the goal of elevating the built environment for the benefit of its end users.

Simply put, biophilic design is good design. It doesn’t have to be expensive or elaborate; it just has to be intentional. Creating connections to the outdoors in the built environment can significantly impact users’ mental and physical well-being.

How Biophilia is Integrated into Projects

There are many ways to integrate biophilic elements into a project’s design. Some of the most common methods of doing this have been categorized by the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) as being either Nature in the Space, Natural Analogues, or the Nature of the Space.

1. Nature in the Space

Biophilic design that places emphasis on bringing elements of the outdoors into interior spaces would be classified as ‘Nature in the Space.’ These outdoor-elements-brought-inside can be anything from plants, animals, and water features, to specific scents, sensations (like the feeling of a breeze), shade and lighting effects, or other environmental components found in the natural world. They are organic features that are literally brought inside. An example of this could be a project using natural materials like exposed mass timber and green walls covered with living plants to mimic the sensation of being in a wooded forest.

2. Natural Analogues

‘Natural Analogues’ in biophilic design are human-made, synthetic patterns, shapes, colors, and other details that reference, represent, or mimic natural materials, markings, and objects without utilizing or incorporating those actual materials, markings, or objects. An example of a natural analogue might be the use of spiral patterns in a painted wall mural to link a project’s design to seashells and the coast, the inclusion of animal print motifs in fabric and material choices, or even the use of blue rugs and carpeting to link a site to a nearby river or other body of water. Subtle finishes, fixtures, and equipment (FF&E) touches can also be a biophilic natural analogue, like the use of shelves that reference the pattern and shape of a honeycomb. Natural analogues are most often design and material choices that pay homage to recognizable environmental elements.

3. Nature of the Space

A focus on the ‘Nature of the Space’ on the other hand, pays more attention to a location’s construction, layout, and scale than its FF&E and other accessories or interior design. It utilizes spatial differences, the geography of a space, and other elements of a project’s configuration to imitate expansive views, sensory input, or even feelings of safety and danger that are found in the wild. This may manifest as an open stairwell that embraces rough, asymmetrical walls to subtly mirror the textures of a canyon, or as the inclusion of an atrium to give end-users a perspective that parallels the wide-open views seen from a mountain peak. ‘Nature of the Space’ can also be seen in the use of soft lighting and smaller scale spaces to simulate the felt safety and coziness of a cave. It is the utilization of a project’s site itself to replicate experiences and sensations found in the world of nature.

By emulating natural features and bringing the outdoors in, architects and interior designers integrate the benefits of exposure to the natural world into built spaces, creating a unique shared experience for a site’s users.

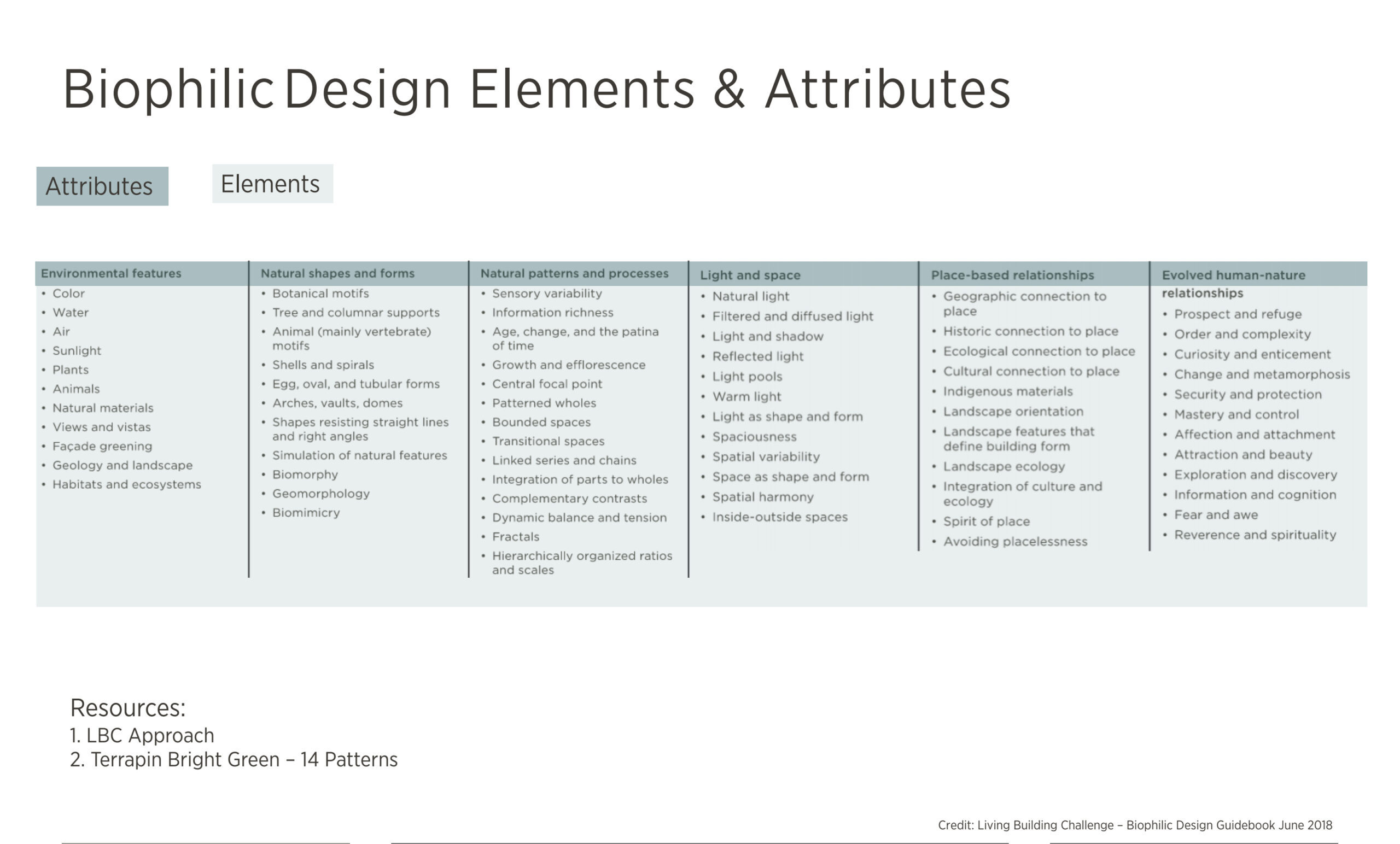

A list of biophilic design elements and attributes.

When combined with intentionality and thoughtful design, these elements can transform ordinary spaces into spaces that support human health and wellness.

The Power of Biophilia

Aside from elevating design, the inclusion of biophilic elements in a project can have numerous positive health benefits for those who use and inhabit that space. Biophilia’s impact on health and wellness may not be something that we are conscious of, but it is a difference that we feel. Humans understand biophilia intuitively.

The amount of time humans spend interacting with nature – as well as the amount of time they are disconnected from the natural world – has real, tangible impacts on an individual’s health. In today’s industrial, technologically dominated world, it’s especially important to seek out connections with nature, since many built spaces often forgo biophilic features and the benefits that come with them.

The negative health impacts of not having enough connection to nature are:

- High blood pressure

- Muscle tension

- Anxiety

- Poor sleep stemming from an unstable circadian rhythm

- A weakened immune system

- Poor focus

- Weak memory

- Attention issues like ADHD

- Fatigue

- Decreased emotional regulation

The positive benefits of exposure to nature, on the other hand, include:

- Lower blood pressure

- Muscle relaxation

- Feelings of safety

- Restful sleep and a stable circadian rhythm

- A strong immune system

- Increased focus

- Greater memory and learning abilities

- Higher energy levels

- Increased emotional regulation

Knowing the range of benefits that biophilia has the potential to provide, architects and interior designers have the opportunity to purposefully design spaces with the health and wellbeing of its end-users in mind, positively influencing the experience of a location as well as the feelings of the people occupying it.

Some of Ankrom Moisan’s expert design teams have already done this, including biophilic elements in the shared spaces of project to elevate the end-user’s experience of those environments. In a follow up blog post, we will take a deeper look at how biophilia shows up in three distinct Ankrom Moisan healthcare projects, discussing how the inclusion of biophilia can be leveraged to support an evidence-based approach to holistic, whole-person care.

New Code Increases Accessibility

Background

At Ankrom Moisan, we work hard to ensure an equal experience for all users of the spaces we design. We explore how to push beyond the expected with accessibility features on projects like Wynne Watts Commons, and we welcome updated codes and standards to address the needs of our community. As the 2021 Building Code takes effect in each jurisdiction, the embedded 2017 A117.1 Standard for Accessible and Usable Buildings and Facilities also takes effect. The new 2017 A117.1 provides significant updates to accessibility clearances based on a study of wheelchair users. The A117.1 is developed by the International Code Council (same authors as the International Building Code). Their challenge is to find the best design criteria for a wide range of abilities, from wheelchair users to standing persons with back problems to persons with low vision or hearing challenges. Ankrom Moisan has participated in their process as an “interested party” in one issue, kitchen outlets, and can attest to the countless hours that go into just one requirement.

At the Ronald McDonald House expansion we wanted to make all families staying for short or long stays be able to use all the amenities, including the common kitchens.

At the Ronald McDonald House expansion we wanted to make all families staying for short or long stays be able to use all the amenities, including the common kitchens.

Changes

Overall impacts to projects by this change are modest, resulting in a few rooms being enlarged by a few inches. While the changes are minimal to buildings, they provide much higher levels of accessibility for impacted users. The most impactful updates are changes to the following requirements:

- In most cases, clear floor spaces grow from 30-inch by 48-inch to 30-inch by 52-inch.

- The turning circle that was a 60-inch “wedding cake” with knee and toe clearance all around is now a 67-inch cylinder with minimal knee and toe clearance.

When looking at a typical privately funded apartment building, the changes are minimal as long as they are understood at the start of the project. There are no changes to Type B units (except new exceptions for kitchens outlets were added), and for the Type A units, the kitchen, bathroom, and walk-in closet may grow a few inches. The trash chute access room will see the biggest change, growing up to 7” in both directions. All these changes are minor when incorporated into the initial design of the building but could be very tricky late in the design process.

There are still some unknowns; If there are Accessible units in a project, they will now require windows to be fully accessible. While the height and clear floor space requirements are easy to meet, we are still searching for a window style and manufacturer that can meet the requirements that windows are operable without tight grasping and less than 5 pounds of pressure to open and lock/unlock.

Our work isn’t done; kitchen outlets were simplified in the corners where a range and refrigerator protrude past the counter with this code cycle, but we must wait for the next A117.1 cycle for kitchen outlets to no longer dictate kitchen design. Ankrom Moisan submitted code changes that are now in effect in the 2022 Oregon Structural Specialty Code and submitted a proposal for the next version of A117.1 and can report that kitchen outlets will no longer drive design or require any special design or construction features in the next code cycle.

At the Wynne Watts Commons the team provided universal design residential units that included cooktops that pull out and upper cabinets lower with the controls shown in the cabinet front.

At the Wynne Watts Commons the team provided universal design residential units that included cooktops that pull out and upper cabinets lower with the controls shown in the cabinet front.

Added complexity with new code change

From a designer’s perspective, the requirements of accessibility have grown exceptionally complex. For example, under the new A117.1, there are now different size clearances for new and existing as well as Type A and Type B units, and the definition of “existing” in the A117.1 does not match the definition in the building code. This adds to the already confusing accessibility requirements that require us to reference multiple documents for any given item (building code with unique amendments by jurisdiction, Americans with Disabilities Act, Fair Housing Act, etc.). Coupled with different interpretations from different experts and code officials it is no wonder why accessibility requirements feel a bit daunting to us and our clients. As an example, California does not adopt the A117.1 but rather chooses to write its own Chapter 11 of the building code with its own unique scoping and technical criteria. And that is just accessibility, our Architects are juggling fire life safety, energy code, constructability, and our client’s budget all while creating great places where communities thrive.

As a firm, we had a challenge to overcome; the new accessibility requirements do not apply to all our projects at the same time. Depending on where they are in the permitting process and the jurisdiction they are in, every project must determine when, and if, they are required to flip to the new code. While most of our projects will be using the new code by early 2024, many will still be under the old code for years to come. We had to develop Revit resources for our project teams that could work for both codes at the same time. Our Accessibility experts partnered with our BIM team to develop a system meeting these goals and requirements:

- It had to be as simple and easy to use as possible for our project teams.

- It had to be blatantly obvious, by a quick glance within Revit, what codes were being shown on any given project.

- It had to provide all the options now allowed by the standards and guide teams to pick the applicable option.

Our solution to this challenge was rolled out to our project teams in September 2022 and provided over 500 updated Revit families.

Below is our graphic of the changes to the A117.1 that affect AM projects. The orange color helps all team members quickly identify the new families are being used.

We have found so many nuances in the accessibility codes that it can be hard to make generic statements. We would love to talk to you about your specific project or topic. Please reach out to Cara Godwin at carag@ankrommoisan.com to learn about accessibility for your project.

* Originally published October 6, 2022, updated 12/01/2023

by Cara Godwin, Senior Associate

Ankrom Moisan’s Healthcare SPAKL Team – Big Focus on Small Projects

The SPAKL team is Ankrom Moisan’s thorough and decisive resource for solving complex and challenging Healthcare project designs. Looking beyond initial or obvious facility concerns and truly partnering with clients for a better understanding of the maintenance and equipment upgrade projects are salient to their success.

Kimberleigh Grimm, Associate Principal, discusses the scope of projects that the SPAKL team undertakes and the challenges that these types of Healthcare projects often present. Kimberleigh’s excitement about and enjoyment of this topic is palpable. She is representative of the strengths and enthusiasm that the SPAKL team brings to the table.

Ankrom Moisan’s Healthcare SPAKL team designing together

Q: What is SPAKL?

A: SPAKL is a subset of the Ankrom Moisan Healthcare team that focuses on specialized, problem-focused healthcare projects. It stands for Special Project Alterations Knowledge League, and it is a team that is experienced in (and committed to) maintenance projects in healthcare systems. We don’t wear capes or fly faster than a speeding bullet – our super-power is the knowledge, enthusiasm, and fun that we bring to this type of project work.

Q: How long has SPAKL been an AM Healthcare team feature?

A: Maintenance projects have always been the core of our healthcare team’s work. SPAKL emerged from internal conversations about creating a focused team with a depth of knowledge in acute healthcare renovation work that is dedicated to increased efficiency, both for us, and our clients. Each project builds on knowledge gained in previous work to enable the next to be even more successful.

Q: How and why does AM Healthcare SPAKL approach differ from other firms’ approach to similar projects?

A: Most firms aren’t truly interested in maintenance or equipment replacement projects. They accept this work to leverage the client relationship for bigger, “better” projects. Because these projects aren’t really valued by most firms, they typically assign less-experienced staff that don’t understand the intricacies of the projects.

This is not AM’s approach. We like what we call the “dirty jobs”. We like them because we understand that they are just as important to a healthcare facility as a new build or a full clinic remodel. We developed the SPAKL team around these types of maintenance projects, and our team is highly experienced in healthcare renovations. We understand the sophistication of these projects in terms of improved patient and staff experiences, reducing construction disruptions and maintaining continuous operations, and understanding existing conditions. We also understand that these projects usually have tight fees (and tighter schedules) and leverage our knowledge and experience with each facility and jurisdiction to maximize efficiency.

Another way we differ from other firms is that we genuinely enjoy this type of work – we love the complexity and the fact that each project is a unique experience.

Q: What makes a SPAKL project unique to other Healthcare projects?

A: We like to say that SPAKL projects are problem-focused, not project-focused. There is a wide variety of projects ranging from equipment replacement projects to maintenance projects to make-ready projects, but the one thing they have in common is that they are intended to address a specific facility concern.

Unlike a typical project that is tasked with helping a facility re-imagine an aspect of their operations, we are problem solvers. Aging equipment? DOH citations? Safety or infection prevention concerns? We evaluate the existing conditions and work with the facility to come up with efficient solutions.

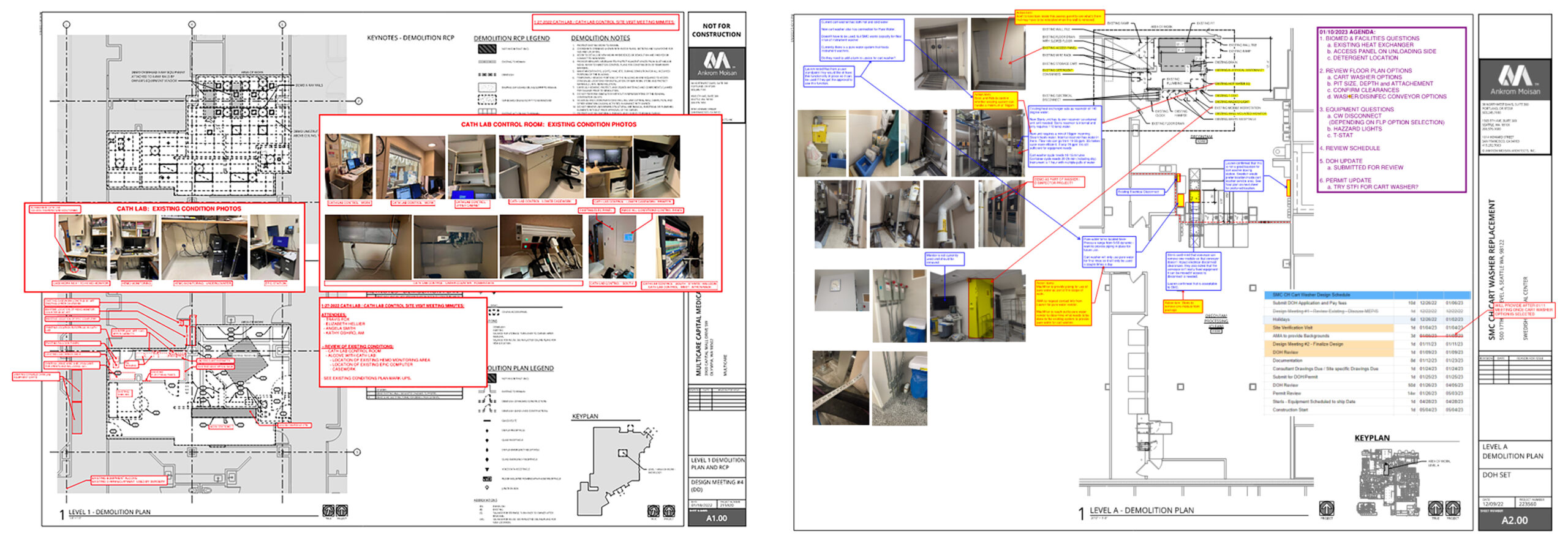

Washer/disinfector installation; Sterilizer replacement

Q: What is the biggest challenge when organizing around the client’s operations?

A: Every project is unique and has its own challenges. Sometimes the challenge revolves around how to minimize disruption during construction. This can range from minimizing infrastructure shutdowns to reducing construction impacts in terms of activity and noise. For example, one project might be concerned about noise impacts to adjacent NICU patient care, while another project’s main issue is minimizing the number of electrical shutdowns required over the project. The key to navigating this is to listen and ask essential questions to fully understand the facility concerns.

Q: What does it mean to “treat them with care”? How do you do that?

A: At AM, SPAKL projects are as significant to us as bigger, fancier projects. SPAKL projects may never generate pretty pictures or win design awards, but they are critical to the functioning of a facility. Replacing outdated equipment increases throughput, improves patient outcomes, and improves both the patient and staff experience. That is critical.

We treat each project with the same care that we bring to the larger projects that we work on. We believe user engagement is crucial, and we work from the beginning to bring the users into the design process so that we can understand both immediate and long-term objectives and concerns. Our style differs from other firms in that we don’t do presentations before the user groups, we host discussions – and we consider the Facility to be the experts in that discussion. It is an open dialog intended to lead us to the best solution. The Facility knows their patient populations, they know their current concerns and what things are working and what is not working. They know what they like and what they do not like. We listen and have an open dialogue, and that is how we get to the best solution for each project. What is right for one facility is not necessarily right for any other facility.

Meeting discussion documentation

Meeting discussion documentation

Q: What are the methodologies that you’ve found most useful?

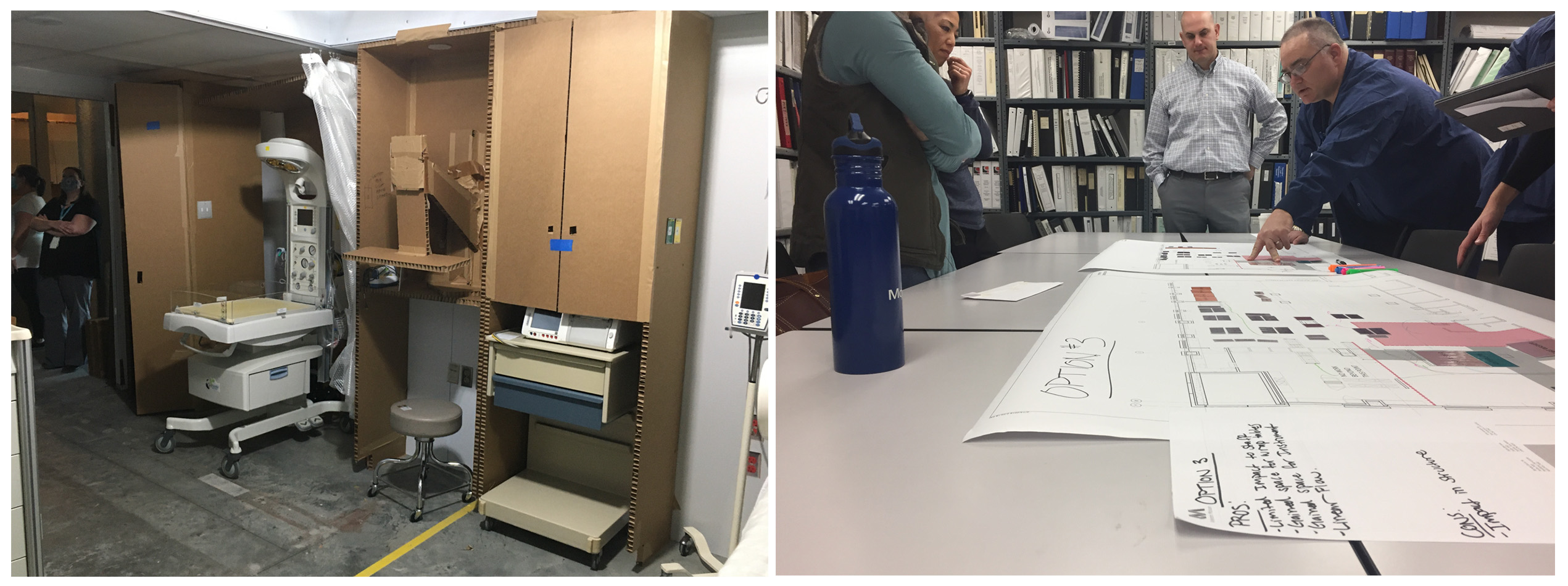

A: SPAKL projects often have tight budgets, and we use a lot of tools out of the LEAN toolkit. We feel that actively involving users in the design process leads to better engagement and better outcomes. For example, rather than providing design options and asking users to pick one, we like to have tabletop exercises where the user group can propose design options of their own and then discuss them. Which means, rather than us telling the users what we think the design solution is, the users are engaged in the design process to test their own ideas. In the end, the user group becomes the best advocate for the final design because they feel ownership of the project and feel heard throughout the process.

We also feel that an early and deep dive into existing conditions is key to a successful project. Existing drawing documentation is great, but it is only part of the story. We want to really understand the totality of existing conditions so that we can anticipate potential problems and address them early in design. You will never hear the words, “we can figure that out in CA” from a member of the SPAKL team. Never.

Full scale cardboard mockup; Tabletop exercise

Q: What are some memorable experiences you’ve had during a SPAKL project?

A: Some of our most memorable projects are also the ones the facility might prefer that we not discuss. And client confidentiality is vital. However, the best thing about SPAKL projects is the variety of work. Every project is unique and has its own set of challenges. It’s one of the things we like best about the work…every week is a new adventure.

One week you may be working on an infant security project and a PET/CT replacement project, the next week you might be working on a central sterile renovation and a sink replacement project. Every project we work on builds a bigger picture of the facility and helps the next project be more efficient.

PET/CT room

PET/CT room

The collaboration that the SPAKL team has with clients is unique and illustrative of the solution-focused approach they are becoming known for. Listening, cultivating deep understanding, and involving the client with the hands-on problem-solving all inform this team’s success, not only on these specialized projects, but with the growing number of clients that return to work with AM for further Healthcare facility updates. Observably, Kimberleigh brings energy and inspiration to the SPAKL team, and has forged a path of thorough discernment of what makes a Healthcare facility project complex and important for the community it serves.

Kimberleigh Grimm, Associate Principal