The traditional idea of an office was losing appeal well before the pandemic made it obsolete. As wireless technology made it possible for people to untether from their desks, many found they liked working in other environments that, while not designed for work, were conducive to it.

Those environments, such as coffee shops, co-working spaces, hotel lobbies, and living rooms, in many ways represent the antithesis of office design and décor. Feminine, nurturing, and sensorially engaging, the comfort they offer seems at odds with productivity.

Moda Tower Lobby, Portland, Oregon

📸: Cheryl McIntosh

Progressive workplaces, however, are finding the opposite to be true. Workplace design that’s informed and inspired by the principles of residential, food and beverage, hospitality, and retail studios is helping drive employee satisfaction and the desire to be in the office, without sacrificing the need for work to get done.

Applying this cross-disciplinary approach requires a nimble team willing to seek inspiration from a wide array of sources. It also requires attention not just to what your office enables employees to do, but attention to what and how it makes them feel.

As with each of the strategies explored in our The Office as Ecosystem series, the benefit also extends to the bottom line. When employees feel engaged and inspired, and their needs addressed, they can contribute in more meaningful ways to the business at hand.

Eager to see this strategy in action? Check out the full series, The Office as Ecosystem, here, with inspiring case studies and examples of ecosystem-thinking applied in the real world.

Erica Buss, Senior Associate, Research & Information Services Manager

Banner photo: Community Transit of Snohomish County, Everett, Washington

📸: Aaren Locke

The Office as Ecosystem: Strategy 2

Improving an office ecosystem only pays off if employees actually come into the office to experience it. And what gets employees into the office? Studies show the strongest incentive isn’t a free lunch, dry cleaning services, or foosball tournaments. It’s other employees.

That means a commute-worthy office is, in essence, one that builds community. The table stakes, like good coffee and comfortable surroundings, are essential, but the communal energy that can’t be replicated at home is the true galvanizing force to get people there on the regular.

2201 Westlake, Portland, Oregon

📸: Moris Moreno

And it turns out, that communal energy is rarely serendipitous. It’s carefully designed into the space. A strategic approach to desk density can create the right level of buzz and activity without sacrificing employees’ abilities to concentrate. A variety of thoughtfully designed spaces for spontaneous and planned collaboration can get people talking and building deeper ties. Areas for curated surprises and engaging employee programming reinforce a sense of belonging to a company that is creative and cares for its people, while also creating reasons to get people together.

When your employees can get their work done anywhere, workplace design stops being about desks, chairs, screens and printers, and starts being about the interactions that make work worthwhile.

Want to learn more? Check out our full strategic roadmap, The Office as Ecosystem, here, or watch this space for our next installment, “The Not-So-Office Office,” coming next week.

Michael Stueve, Principal, UX Strategy

Banner photo: Buchalter, Portland, Oregon

📸: Magda Biernat

The Office as Ecosystem: Strategy 1

The Office as Ecosystem approach has 3 key tenets:

- The well-being of one lifts the prospects of all

- Fostering connections between people is the primary function of the office

- Productivity is a by-product of belonging

When we think about and design for the office as an ecosystem, we’re essentially saying that if one area, department, or person is underserved, the workplace as a whole will suffer. Likewise, we acknowledge that moves toward inclusion, equity, and belonging benefit not just the person or people for whom they are taken, but everyone in the greater workplace community.

This kind of people-first thinking and design can manifest in small, easy-to-implement tactics, as well as larger, systemic shifts.

At a systemic level, there’s a paradigm shift from the office in service of a business function to an office in service of individuals, each of whom brings different needs as well as gifts to the ecosystem. This requires abandoning both the one-size-fits-all, as well as the set-it-and-forget-it mindsets. Instead, it requires companies to embrace custom solutions, curiosity, and continuous improvement.

Aspect, Portland, Oregon

📸: Christian Columbres

This can be as simple as inviting a wider array of people with a more diverse set of perspectives to the proverbial table when it comes to office planning and design, asking what they need and building solutions together. Truly ecosystem-focused companies might even go a step further and imagine the needs of future staff and visitors, envisioning a truly welcoming environment for people of all abilities and backgrounds. In this way, companies become attractive to a wider, more diverse, and more engaged talent pool, and avoid the need to react and retrofit with each new hire.

Tactically, there are new, people-first solutions emerging every day that allow workplaces to serve the needs of the individuals within their workforce. Straightforward but ingenious solutions, such as furnishings that support fidgeting or fit a variety of body types not only accommodate differences but celebrate them. Visual cuing systems for d/Deaf persons meet a specific need, but also raise the consciousness of everyone in the office about the myriad ways people receive and process information. Imagine the impact when that understanding gets translated to customer, client, or shareholder interactions. When people-centered design becomes the “norm,” everyone in the workplace community – and often well beyond it – benefits.

Want to learn more? Check out our full strategic roadmap here, or watch this space for our next installment, “The Commute-Worthy Workplace,” coming next week.

Bethanne Mikkelsen, Managing Principal, Interior Designer

Banner photo: Fox Tower Green Room, Portland, Oregon

📸: Shelsi Lindquist

Where are the Women?: Closing the Gap

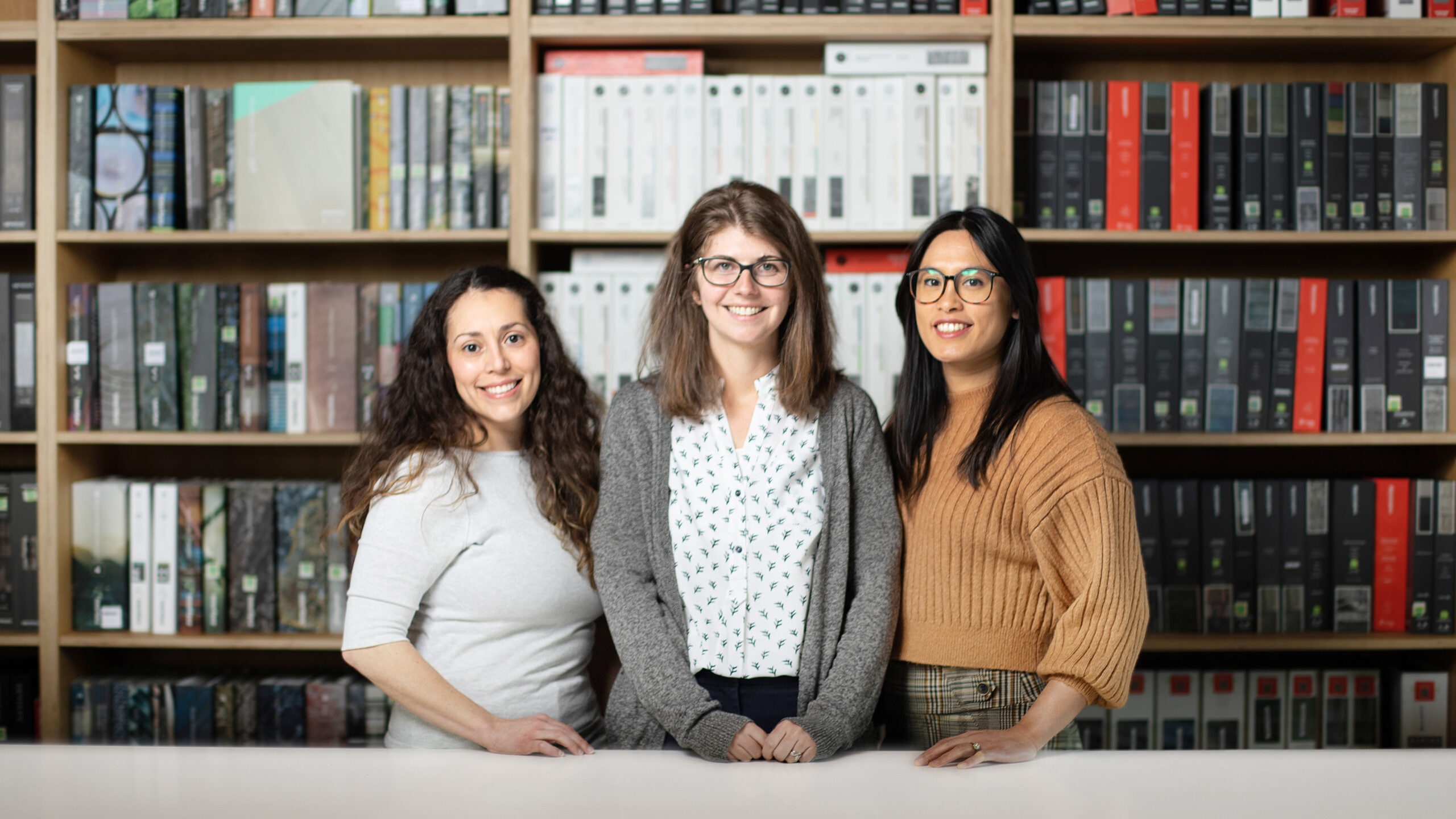

Backed by Ankrom Moisan’s Do GOOD / Be WELL research scholarship and galvanized by a noticeable lack of women in architecture, Amanda Lunger, Elisa Zenk, and Stephanie Hollar set out to determine why women are not at the forefront of the field, and what can be done to get them there.

Elisa Zenk, Stephanie Holler, and Amanda Lunger in AM’s Portland office.

The Research

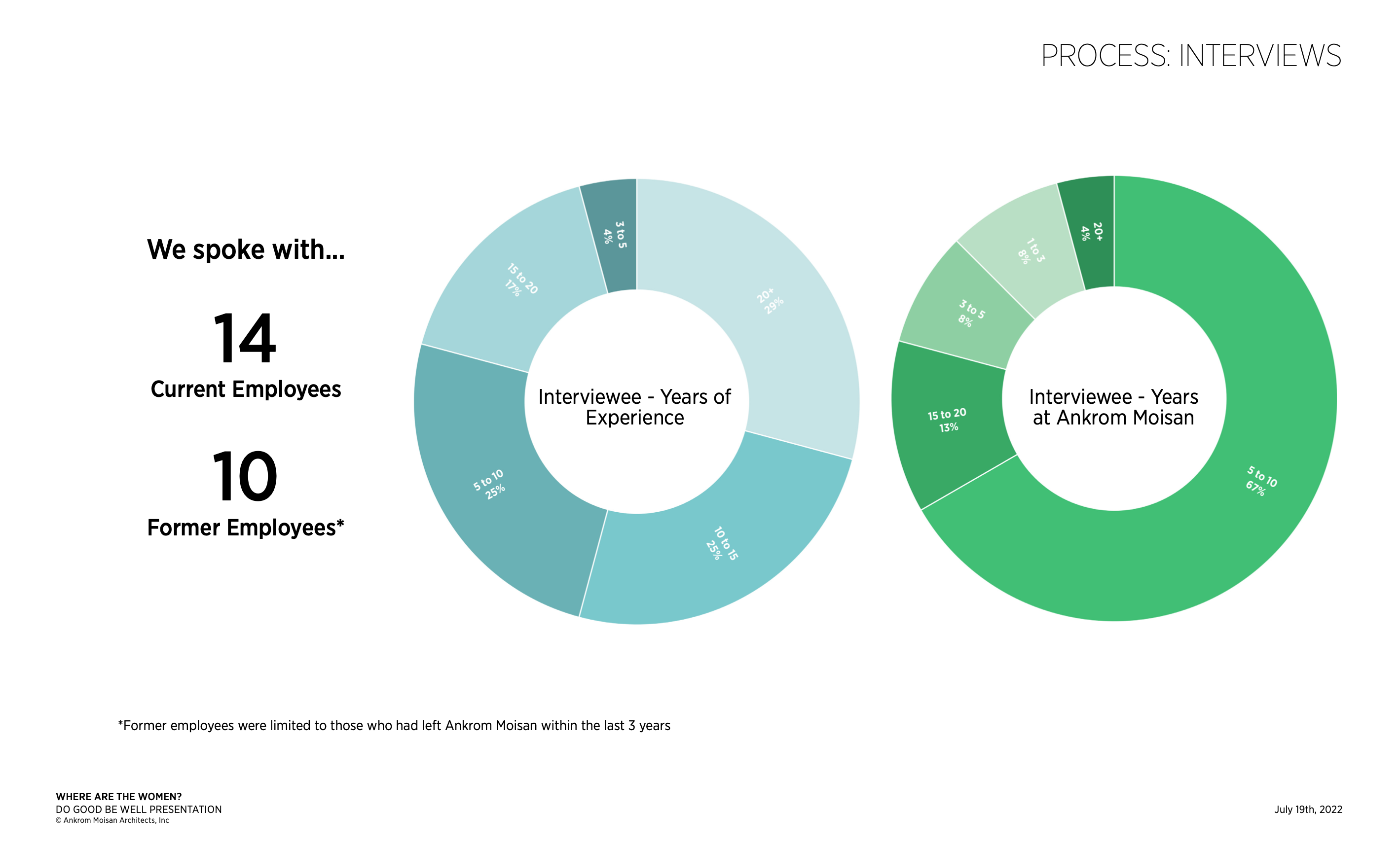

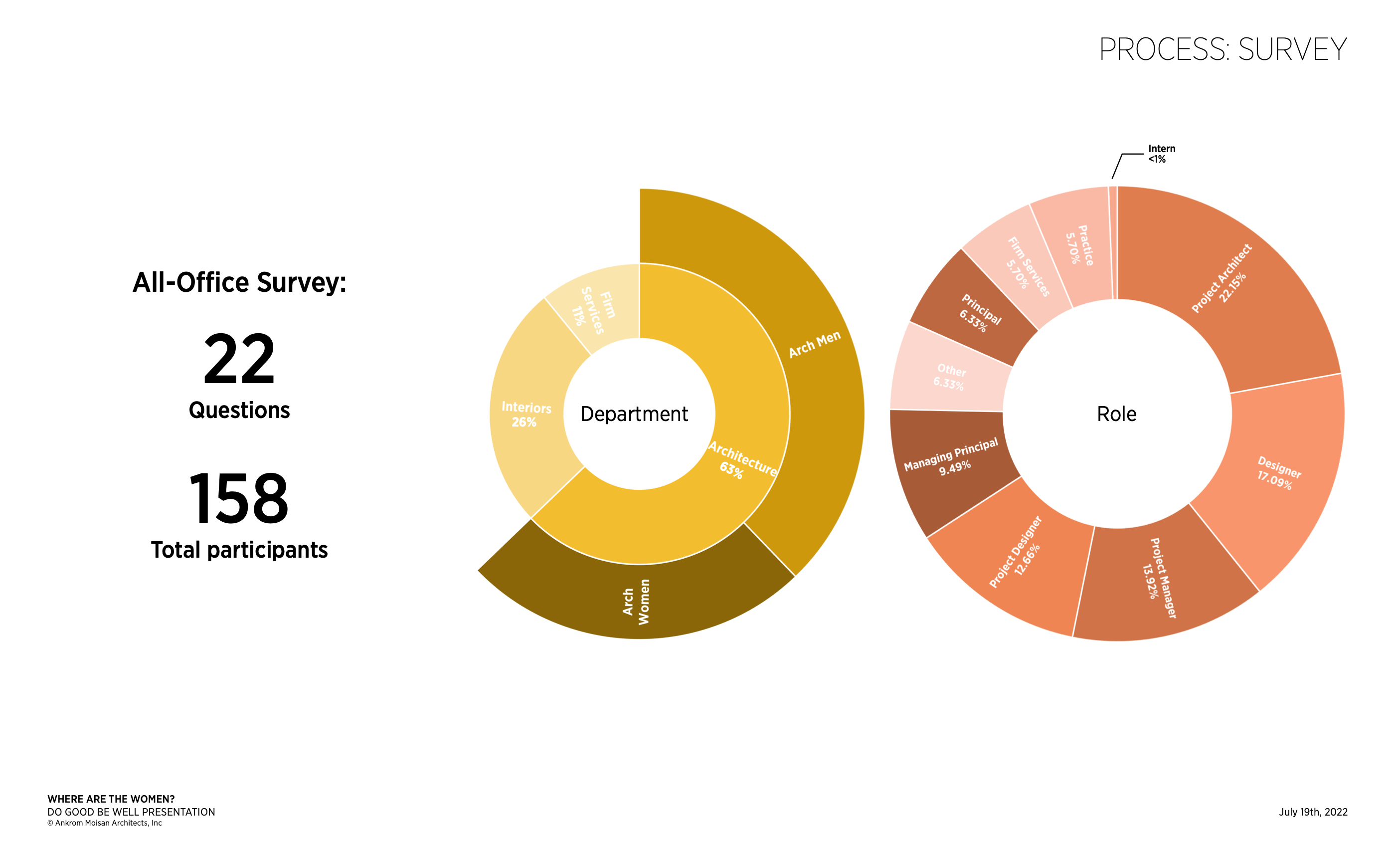

Amanda, Elisa, and Stephanie did this by administering all-office surveys, holding conversations with women in the field of architecture, evaluating their own individual experiences at Ankrom Moisan, and conducting case-studies that observed the structure and operation style of women-led architecture firms. The all-office survey contained twenty-two questions and was answered by 158 participants, both male and female. As for the conversations with women in architecture, fourteen of those women were current AM employees, and ten of them former AM employees.

What these conversations, surveys, and case studies revealed was eye-opening, but not out of left field. A substantial disparity exists between men and women’s experiences in the architecture industry. This article will highlight the primary problems afflicting women in architecture and provide methods for both firms and individuals to combat and overcome them.

Amanda, Elisa, and Stephanie identified 6 key issues:

- An Unclear Path to Leadership

- Burnout

- Pay Disparity

- Balancing Motherhood and a Career

- The Road to Licensure

- Feeling Out of Place

While these findings may paint architecture as a lopsided and unfair industry, the good news is that there are many ideas and suggestions for how to boost equity and support women in architecture. Some of the ideas, presented at the 2022 AIA Women’s Leadership Summit in San Jose, California, which Amanda, Elisa, and Stephanie attended, range from celebrating the successes of other women, reminding individuals to ask for help when needed and remembering that it’s okay to say no, to making time to mentor younger women, and delegating and sharing opportunities with other colleagues. Some suggestions are as simple as taking ten minutes at the beginning of every meeting to create a psychological safety zone, so that everyone feels like they belong at the table and can express themselves without fear of rejection.

Jennifer Sobieraj Sanin, Elisa Zenk, Stephanie Hollar, Mariah Kiersey, and Amanda Lunger at the 2022 AIA Women’s Leadership Summit.

Additionally, Amanda, Elisa, and Stephanie have provided their own insights for how Ankrom Moisan, and other architecture firms, can remedy the gap between men and women in the field. Other potential solutions suggested by a variety of sources—from interviews with women in the field and from solutions other firms have implemented—synthesized through Amanda, Elisa, and Stephanie’s research will be interwoven with the six key issues they identified.

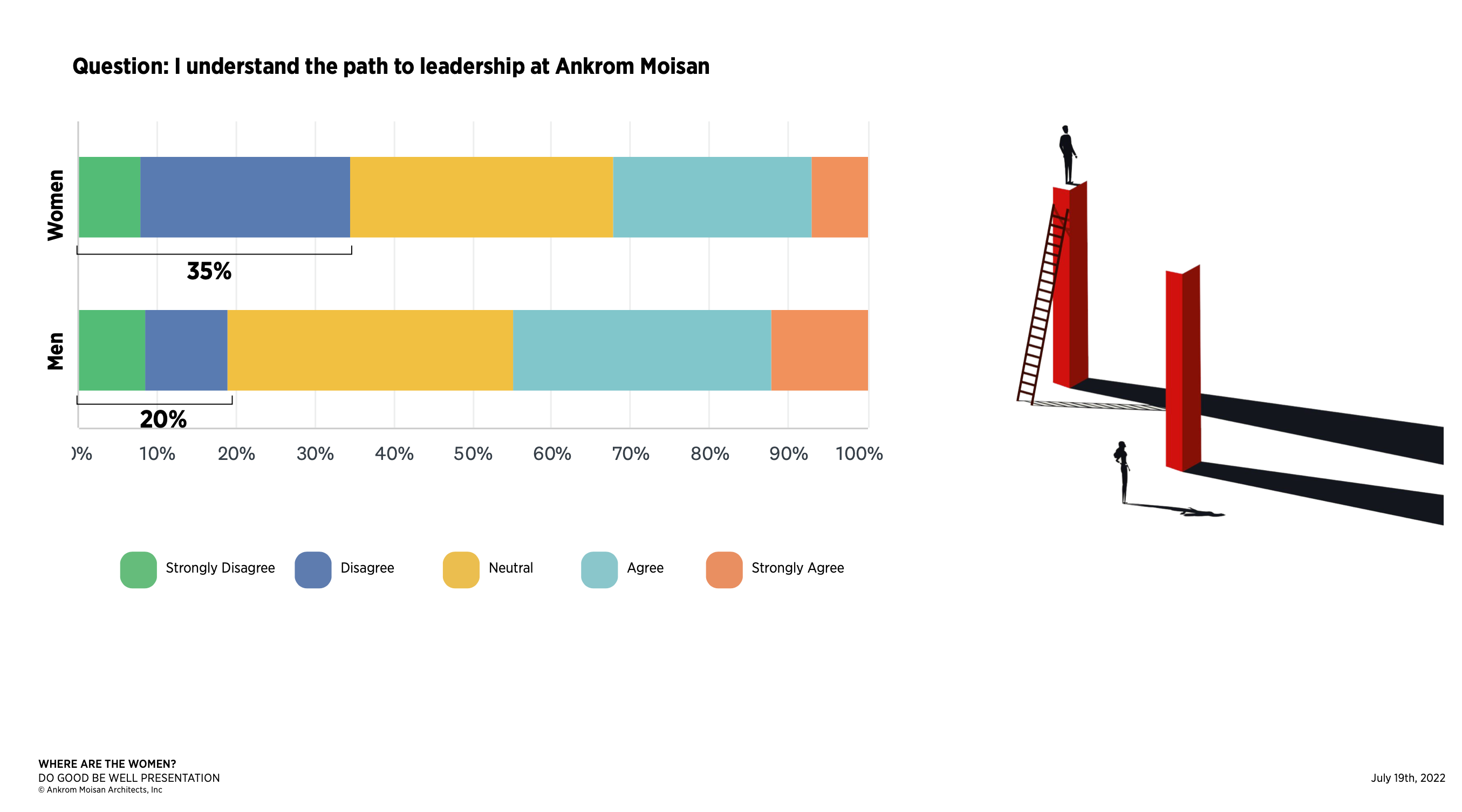

An Unclear Path to Leadership

Leadership is a common goal for both men and women in architecture. 70% of the people surveyed by Amanda, Elisa, and Stephanie stated that they would like to be in a leadership position. Unfortunately, women seemed to feel that goal was out of reach. One employee surveyed responded that they “truly wish to hold a leadership position someday but have zero expectations that they would ever make it into [one].” Another answered that a leadership role was desirable but seemed like “you are inundated with paperwork and peopling and are no longer a part of the design of architecture.” The desire to still be a part of hands-on design processes may be a factor in forgoing the pursuit of leadership roles, but it is not the sole reason leadership can feel out of reach to female architects.

This dashing of expectations may be attributed to the observation that the path to leadership roles is less than clear for women in architecture. 35% of women felt that they didn’t understand the path to leadership at Ankrom Moisan, whereas only 20% of men felt that the road to leadership was beyond their grasp. There were some other survey respondents, however, who saw this lack of clarity regarding career advancement as a challenge, stating “I have no one to look up to that looks like me. So, I’ve decided to become that person – a leader.”

Survey results highlighting an unclear path to leadership positions.

One reason the ladder to success might appear so esoteric is that a lack of evaluations and constructive feedback can work as a barrier against career growth and advancement. Luckily, through their research, Amanda, Elisa, and Stephanie were able to gather ideas for how to break down this barrier and make the path to leadership clearer. These suggestions range from designing strategic plans like PEP employee evaluations and check-ins for developing staff into leadership roles and standardizing them across teams, to adding peer reviews to the evaluation process for a broader spectrum of feedback.

Taking these suggestions to heart, Ankrom Moisan’s Career Pathways Program establishes resources for employees to understand the path to leadership, making it the most significant action item to come from Amanda, Elisa, and Stephanie’s research. Another key solution that emerged from this project was the hiring younger staff for employees to mentor and lead, thus creating ‘inward facing’ roles for many of the architects that desire to hold a leadership position and providing younger hires with mentors that they can look up to and learn from.

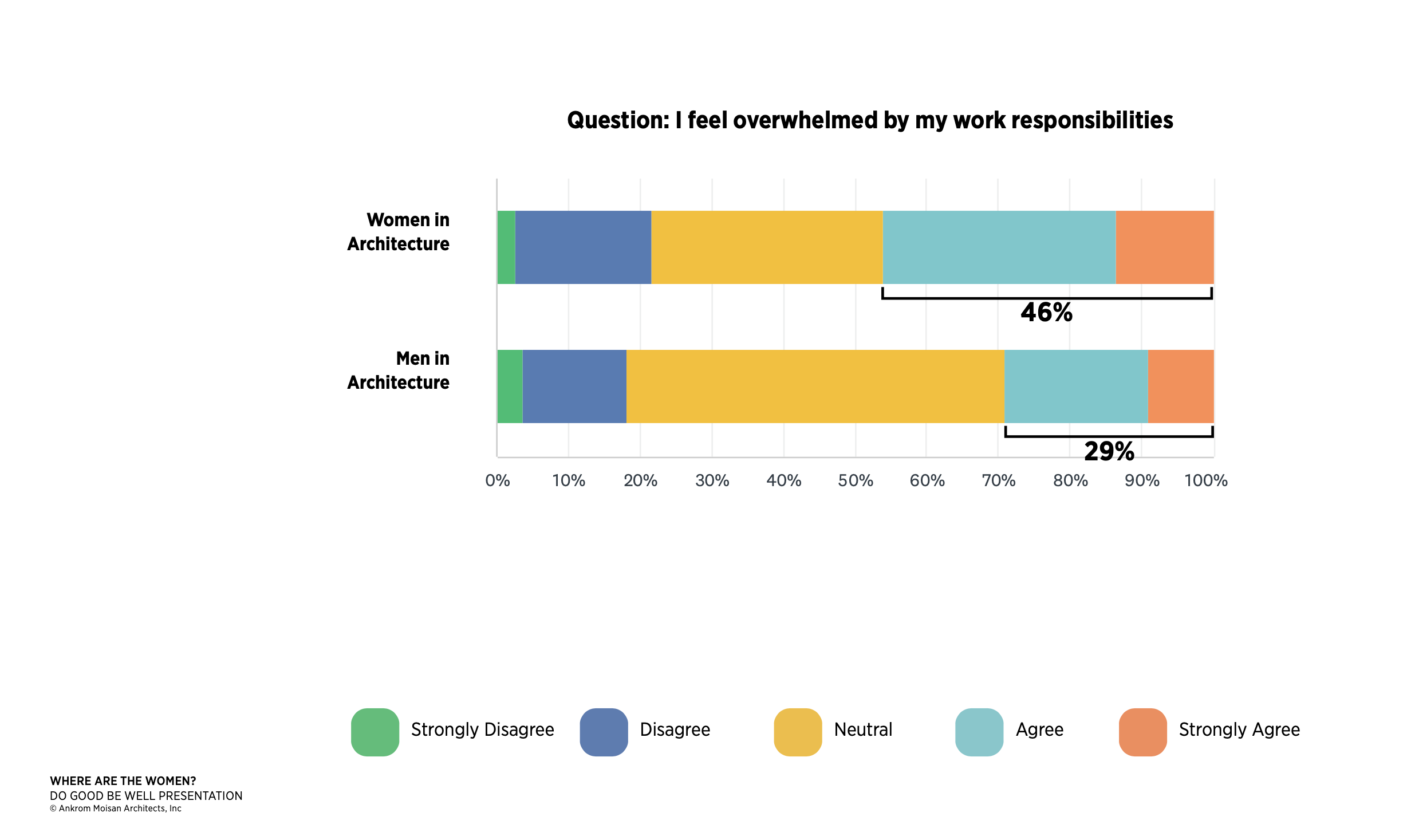

Burnout

When employees take on additional work and responsibilities beyond their regular role, they become overworked and have little energy left for their regular duties. Adding newer, younger staff to architecture teams would also help solve the burnout problem, which is primarily caused by a staff shortage. Unfortunately, it seems that burnout happens to women at a disproportionate rate. 46% of women have felt overwhelmed by their responsibilities at work, which is drastically more than the 29% of men who feel that way.

Survey results related to staffing, workload, and burnout.

The feeling of being overcome by professional obligations often prevents employees from wanting to advance in their career, as well, as that advancement presumably comes with even more responsibility. One survey response elucidated, “I enjoy working with the people and the clients we have, but not always having the resources to staff a project can lead to burn out, make it hard to want to be involved in any initiatives, and really leads to questioning what it means to [want] to advance.” Some of the solutions suggested by Amanda, Elisa, and Stephanie to combat this are to focus on hiring and retaining emerging professionals, ensuring that employees who feel overwhelmed have the opportunity to move to less demanding projects with lighter workloads, and designing strategies to ensure that staff are not spread too thin, or constantly in ‘survival mode.’

Pay Disparity

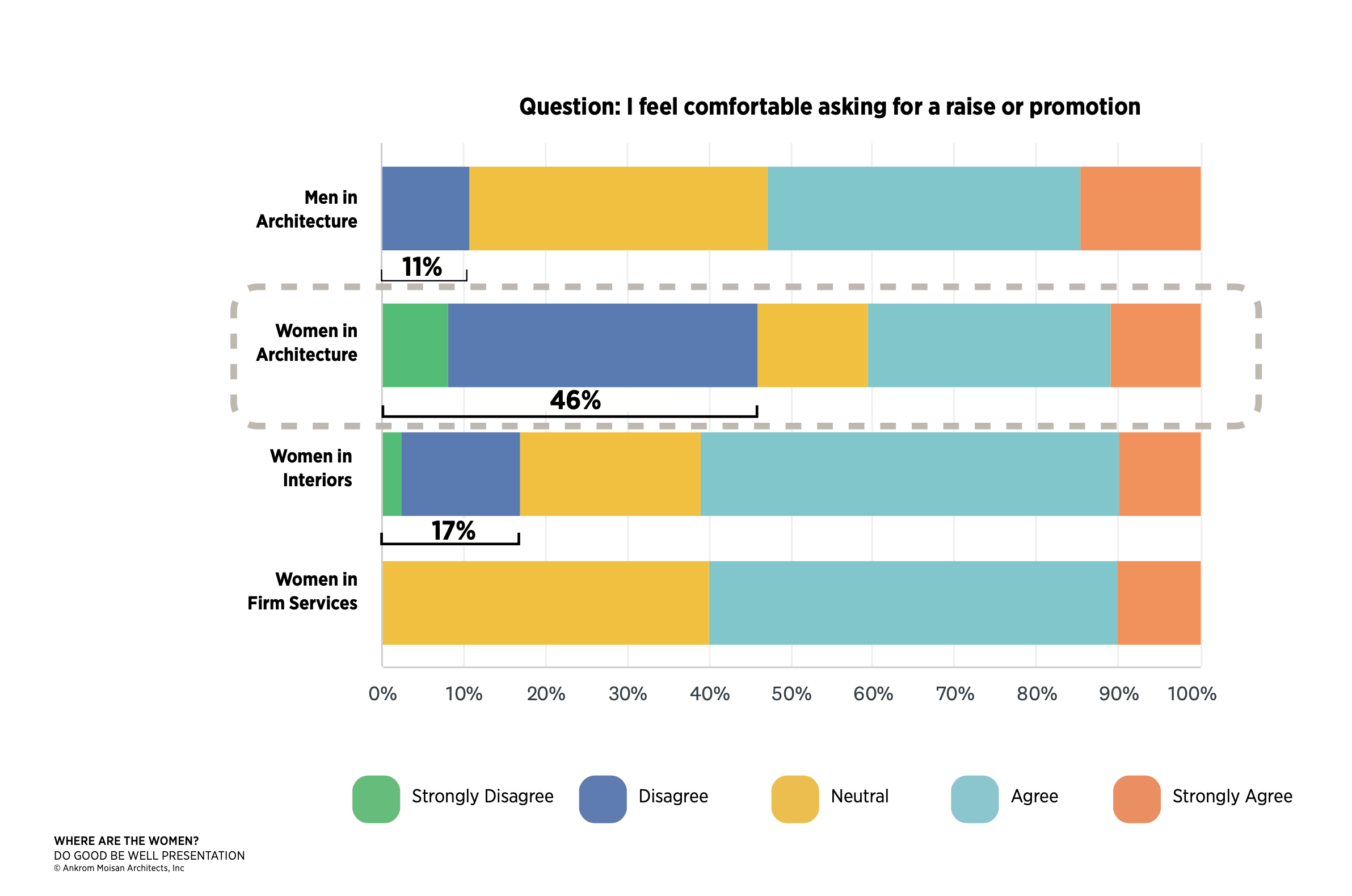

It’s common for employees who take on extra work to receive a pay raise with their new responsibilities. This is not always the case, though, and sometimes individuals must negotiate to secure an increase in their salary. Yet again, this is an area that is not entirely equitable. In fact, negotiations have the largest discrepancy in attitude between men and women in architecture. 46% of women surveyed admitted that they do not feel comfortable asking for a raise or a promotion, which compared to male respondents’ 11%, is eyebrow-raising. One discerning observation that reveals why this is the case indicated that “women typically ask for a raise after they’ve [proven] that they’ve done something, but men ask for a raise in anticipation that they’re being asked to do something.” Ultimately, this means that women may be doing more work for less reward than their male counterparts, as they feel they must go above and beyond before they are entitled to additional compensation.

Survey results related to negotiations.

Another component to this issue is pay transparency. Not knowing the pay range for a position when entering negotiation can set a person up to settle for less than they deserve. Additionally, a lack of transparency can prevent people from wanting to negotiate in the first place. As one survey respondent put it, “I haven’t been super confident, and I didn’t want to come across as pushy. I also didn’t do it because I wasn’t aware what other firms offer.” A potential solution for this, it seems, is offering confidence and negotiation workshops for women while proactively checking in on pay and role satisfaction, ensuring that companies are candid about the salary ranges for all their positions prior to negotiations. A case study observing Jeanne Gang’s Studio Gang found that knowing the baseline salary for any given position is key for enacting change, for yourself and others.

Because pay has been ranked as the second most important aspect of an individual’s career in an AMA office-wide survey, just after work-life balance, being transparent about salary ranges is crucial for both recruiting and retaining employees. It’s known that staff who feel that they’re being paid below the market value are 49.7% more likely to search for a new job within the next six months in comparison to employees who feel they are compensated at or above the market rate (Payscale). While about a quarter of both men and women were unsatisfied with their earnings, there were 27% more women than men who felt that the pay range for their role was not clear enough. Proposed solutions for ensuring pay ranges are as transparent as possible include conducting regular pay audits to identify and correct inequities, publishing pay ranges for each role, and communicating with staff about how those ranges are determined.

Outreach is another method to secure the place of women in architecture that great strides can be made in. By talking with female architecture students, conversations can be started around fair wages and negotiation, so that the next generation of women architects are already equipped to face the challenges of the industry. Additionally, encouraging employees to take part in programs such as Architects in Schools, ACE Mentorship, and the Boys and Girls club can expose more youth to the field of architecture, ensuring that its future is bright, and that burnout no longer holds back staff from doing their best work.

Balancing Motherhood and a Career

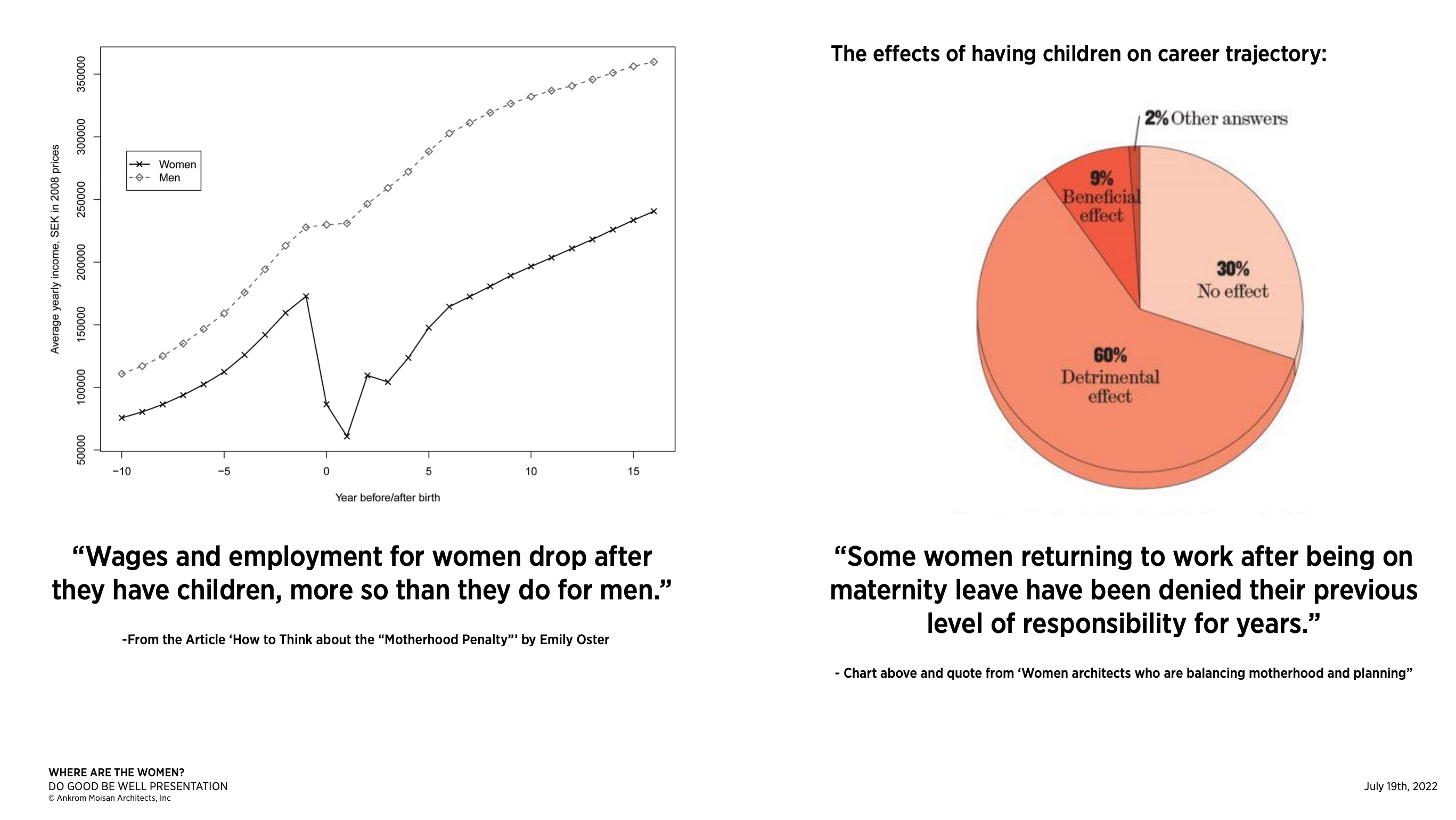

One area that undoubtedly impacts women and their careers more than their male counterparts is having children. Of the surveyed employees, half of the men who responded did not believe that having kids impacted their careers, while only 30% of women could say the same.

Graphic representations of the impact childbirth has on the careers of women.

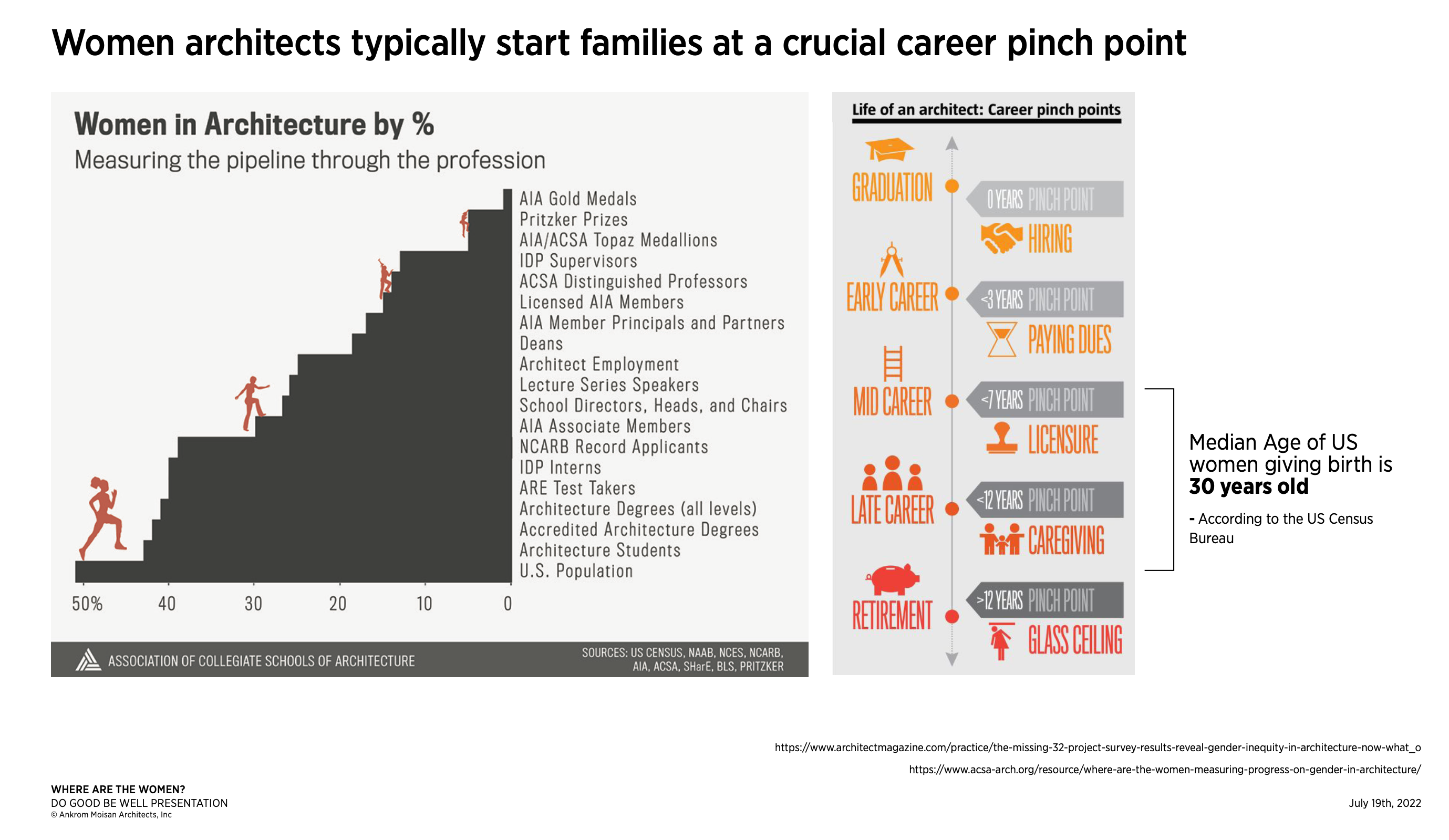

Often, female architects start families at crucial career pinch points. If they choose to have children, it is not uncommon to return from maternity leave and be denied the same level of responsibility that they had previously held for years. The professional uncertainty tied to having children can mean that working women have to choose between one or the other. Some women try to juggle both motherhood and advancing a professional career but find that “being a mom and an architect, [it can feel] like both suffered.” Others draw a line, declaring that they are “not willing to sacrifice [their] personal or family time in order to advance [their] career.” Still, it’s hard not to feel like they are missing opportunities male counterparts don’t have to give up.

Illustration of how children come at a pinch point for many women’s careers.

There are ways to counter this feeling, though. Firms can provide better parental relief, for both men and women, normalizing child-rearing as the responsibility of both parents, rather than the sole responsibility of a mother. Promoting flexible work schedules can also help parents look after their children without sacrificing their career. Finally, firms can subsidize childcare, reducing the need for mothers to have to choose between their kids and their careers. At MOYA Design Partners, a childcare stipend is included as part of the work benefits project. Another case study found that Architects FORA, a 100% women-owned firm, is staffed completely remotely to provide as much flexibility as possible for employees with families. Whether children are young or old, this surely makes a difference in balancing professional obligations and a healthy home life.

The Road to Licensure

Motherhood is not the only thing that can set back a woman’s career. Licensure also serves as a roadblock on the path to leadership, especially for women. Although 61% of male architects are licensed, only 40% of women are. Employees that spoke to Amanda, Elisa, and Stephanie stated that “becoming licensed has been a daunting task.” Though supervisors can be supportive, encouraging employees to take the Architecture Registration Examination, “trying to excel with work responsibilities, office initiatives, and activities leaves little time for work-life balance, finding time to study for the ARE’s, and general decompression from it all.”

A healthy work-life balance is integral to both quality of work and quality of life. It’s necessary to protect this balance without penalizing employees who forgo studies and examinations that occur outside of working hours. Suggested solutions include incorporating ARE study and testing hours into staffing plans, reexamining the requirements to become a principal, and offering greater incentives for passing the Architecture Registration Examination and completing the process licensure. If these steps are undertaken, it’s possible that firms will see more licensed female architects, and women architects in leadership roles.

Feeling Out of Place

Outside of architecture firms, women face even greater challenges. “It’s difficult to be taken seriously as a woman in architecture, especially as a young woman,” one survey response said. “Not so much amongst other architects, but to GCs and consultants I feel like we have to prove our knowledge and worth 100 times over.” Another respondent noted that “it’s really hard when you’re asking someone like me, [a] thirty-something-year-old woman to bring in business. I have nothing to relate to 65-year-old men. How am I supposed to cultivate those relationships and bring in business?”

These challenges often originate from sexist stereotypes and beliefs regarding the kind of work women can do. The best way to put an end to beliefs like this is to train staff, especially men, to be allies to women in their field. It is imperative that men are aware of the challenges that women face in architecture, that way they can advocate for their co-workers in beneficial, productive ways. Firms can also accelerate the implementation of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion strategies, and work with (or continue to work with) women-owned consultant firms to ensure that women in architecture are supported and celebrated.

Of course, it must be acknowledged that none of these issues stand alone. Many of them intersect in complex ways, preventing women from making the most of their experiences in architecture. For example, having children can prevent female employees from taking the time to complete licensure, which may bar her from working on more projects that could potentially advance her career to the level of leadership. Alternatively, having too much work and being spread too thin can stop her from mentoring younger staff, taking the ARE, or even deciding to have kids. These are tough choices that nobody should have to make; a career and a family should not be mutually exclusive.

Making Progress

What is worth celebrating most, though, is the fact that Ankrom Moisan is already executing many of the ideas recommended by the DEIB Council to fight these issues. Benefits like Flex holidays and remote and hybrid work options allow women with families to devote time to both their career and their children, on their own schedule. Programs such as AM Learn encourage employees to continue their professional growth through educational opportunities like the office’s regular Lunch & Learn sessions. Annual DEI surveys and listening sessions from The Diversity Movement promote conversations around these topics, certifying that everybody’s voice is heard. Do GOOD/Be WELL research projects provide an outlet for investigating critical issues to improve overall company culture.

Furthermore, Ankrom Moisan is committed to establishing clear career pathways, explicit evaluation criteria, and equitable pay transparency for all positions. This initiative led to the creation of the Career Pathways Program, a practical resource which summarizes the relationship between roles and titles in architecture, interior design, and practice services, with the hope of clarifying the pathways for professional development and growth available to Ankrom Moisan employees. Informative charts and diagrams illustrate our disciplines’ roles, role summaries, and evaluation criteria at all levels. All of this goes to ensure that our HOWs are fully embodied, every day.

There may be a lot of challenges when it comes to safeguarding gender parity in architecture, however, what Amanda, Elisa, and Stephanie have done with their Do GOOD/Be WELL research project is confirm that there are plenty of actionable solutions that guarantee the future of architecture is indeed female.

Amanda Lunger, Stephanie Hollar, and Elisa Zenk in the Portland office.

By Jack Cochran, Marketing Coordinator

Where are the Women?: The Research

The Do GOOD / Be WELL scholarship encourages Ankrom Moisan employees to research an open-ended topic of their choosing to discover and share the practical results of their findings with the firm, industry, and community at large. The scholarship, started in 2017, is sponsored in memory of former AM employee Carolyn Forsyth, an inspirational leader and unyielding force for change. Intended to honor her legacy of sustainability, equity, innovation, advocacy, education, and leadership, the DGBW scholarship elevates and empowers new and inspiring ideas within Ankrom Moisan and the broader field of architecture, pushing us all, as the name implies, to do good and be well.

For their research scholarship, Amanda Lunger, Elisa Zenk, and Stephanie Hollar ventured to ask: Where are the Women?

Amanda, Elisa, and Stephanie atop Ankrom Moisan’s Portland office.

The idea came to them naturally. During the firm’s 2020 Women’s Day celebration, Elisa noticed that some of the AM statistics shared didn’t seem to tell the whole story. “The women in architecture numbers were getting buried in the celebration of the fact that our office had this large percentage of women,” Elisa explained, “but when we looked into it, most of that percentage was made up of women in the interiors department and various overhead positions.” The real number of women in architecture was not as equitable as it could be. “I think I already knew this intuitively, that women are underrepresented in design roles,” Amanda disclosed, but “once we actually looked at those numbers, that was kind of shocking to me.” Stepping back to all architecture roles, not just design, women only make up 37% of architecture staff nationwide, according to AIA industry data collected in 2019. Amanda, Elisa, and Stephanie all knew that there should be more women in the industry and began to question why that was not the case. They were also interested in solving that problem at our firm, pushing AMA beyond industry trends.

After Amanda, Elisa, and Stephanie discussed this observation, they agreed that they had seen too many brilliant women, presumably on track for leadership, leave the field. “We were talking about these women who were really rockstars in the architecture department who were leaving,” recalled Amanda. “We were speculating as to why the industry seemed to have that problem.” Whatever the cause, it was clear that some women were dissatisfied with their experiences in architecture.

Stephanie recognized that the issue of women in architecture leaving Ankrom Moisan for other opportunities was one that needed a deeper investigation. It was also a problem that affected her directly. “The women who we saw leaving at that time were older than me and in architecture, but then they left. I saw them as people that I was looking up to [that] were mentors and having them leave really created a gap of future women architecture leaders,” she remarked. “It makes you kind of question your own career sometimes. Like if all these other women are leaving, it’s like, OK, what am I doing here? Like what are they finding elsewhere?”

In fields traditionally dominated by men, like architecture, same-sex mentors are paramount to the success of early career women. Female designers are more likely to aspire to career advancement if they see someone like them at the top. This role-modeling is critical for the retention and professional growth of our talented female architects.

The consequences of the lack of female representation in architecture was further emphasized by Amanda, “Being a woman in architecture, I’ve run into a lot of experiences in dealing with colleagues where I felt very misunderstood and kind of lonely as being a gender minority or marginalized gender in this industry. I’ve had personal experiences sitting in a meeting with consultants and some of my project team members, who are all men. At the beginning of the meeting, they’re all talking about working on their cars, or fishing, like these shared hobbies that they have. I had a hard time finding common ground. It was hard to know where to start [building rapport] in some of those cases. I felt like I got overlooked a lot of the time.” Elisa felt similarly, noting how being the only woman in the room “makes it hard to have a voice or feel comfortable having a voice. There’s not always room at the table, even if you’re sitting there.” Elaborating on this idea, Amanda reflected, “I feel like I was always looking for a woman who had been in that position before and could give me advice like how to cope and how to get through it. But those mentors just weren’t there.”

The exodus of women from established architecture firms becomes even more lamentable once one recognizes that the leadership positions and characteristics women tend to embrace are critical for the future success of the firm; roles and traits such as “inspiration, participative decision-making, setting expectations and rewards, people development, and role modeling” (McKinsey, 2018). Simply put, a workplace with more women is a workplace with more creativity, productivity, and profitability (MIT News, 2014). The lack of women in architecture is intrinsically detrimental to everyone in the industry.

The healthcare team working together in the Seattle office.

Amanda, Elisa, and Stephanie’s interest in what happened to these women came at the right time. It was about a week before applications for the Do GOOD / Be WELL scholarships were due, and after their initial conversation, Amanda thought, “maybe we should turn this into a research project, that way we have time set aside to really look at it. I mean, nobody else was doing this research, so it kind of felt like, well, if we don’t do it, who’s going to?” The group quickly put together an application and submitted it before the April 2nd deadline, a date shared with Carolyn Forsyth’s birthday.

Many of the data points collected during the project’s research were gathered from conversations with women architects about their professional experiences, career goals, the tools that helped them succeed, and what they thought firms could do better to support their growth. Additional observations came from personal experience, while other statistics were sourced from the AIA. The bulk of Amanda, Elisa, and Stephanie’s AMA-specific statistics originated from a firm-wide survey they conducted, which gathered responses from 158 participants, both male and female.

Graphs illustrating the research project’s interview and survey process.

Stephanie disclosed that the study they conducted was designed to provide “specific points that we could apply here at Ankrom to help [combat the disappearance of women from architecture].” The idea was that by identifying the roadblocks that women face when advancing in their careers, they will be able to more confidently advocate for themselves and the resources they need to grow as professionals. The research is an important first step in Ankrom Moisan’s journey to bringing gender parity to the architecture department and increasing diversity, equity, and inclusion in the firm overall.

Read part two, here, to learn more about what the research uncovered.

By Jack Cochran, Marketing Coordinator

The Office as Ecosystem

Our workplace design team has a unique window into the changing nature of work, and the challenges that companies have keeping up with it. Every client meeting we attend, and every new design request we field, gives us a view of what’s really going on in today’s offices.

Late last year, we started to see some patterns emerge in the conversations we were having with clients about their workplace needs. And those patterns lined up with some trends and tactics we’d been incorporating into our projects.

It just made sense, then, to turn those patterns into a strategic roadmap our colleagues and clients could use as they are all rethinking what the workplace looks like. It examines the ways we need to shift our thinking about the roles, both functional and emotional, that offices play in workers’ lives today, with lots of examples and ideas to get begin the journey of workplace transformation.

We call the overarching approach “The Office as Ecosystem,” because it acknowledges that the workplace is an interconnected environment, where the well-being of one lifts the prospects of all.

If you’ve been grappling, as so many companies have, with a changed workforce and a not-so-relevant workplace, maybe a shift to ecosystem-thinking is in order.

Archivist Capital, Portland, Oregon

📸: Josh Partee

Check out the full strategic roadmap here, or watch this space for each installment, starting next week:

Part 1: The Office Gets Personal

Part 2: The Commute-Worthy Workplace

Part 3: The Not-So-Office Office

Part 4: New Ways to Meet

Part 5: Culture First Employee Engagement

(each Part will be hyperlinked once the blog post launches)

Banner photo: Buchalter, Portland, Oregon

📸: Magda Biernat

Living Our Hows Series

These are our Hows, the values by which we work and play. We created our Hows a few years ago through a decade-long process (stay tuned for a future post detailing that process!). We encourage everyone to show up in life and at work authentically, to seek connections and embrace the work we do with enthusiasm and flexibility. We’re a hybrid firm, and we work differently.

Our workplace design team has put together a six-part series that touches on our Hows and the way they come to life at AM. Click the links below to read each article in the series.