In architecture and urban planning, masterplans are strategic documents that design, organize, and plan for the development of a large site or area containing multiple blocks or buildings. They provide a comprehensive framework for the development of an area of land to be used, whether it is for housing or other building types, infrastructure, or open spaces for a community or certain property. They establish the overall vision for a property that allows for coordinated decision-making as individual building or infrastructure projects are designed and implemented over time.

Ankrom Moisan has worked on many buildings within larger masterplans throughout California’s Bay Area as part of Special Use Districts or Specific Plan Updates. We enjoy working on these projects since they have the potential to make a tremendous positive impact on the area where they are constructed, which is exciting. Masterplan projects can create thriving new neighborhoods or contribute to a massive infusion of jobs, housing, and community amenities that reinvigorate existing – yet stagnant, historically under-invested, or under-resourced – neighborhoods. One of our recently completed projects, The George, a 20-story high-rise in San Francisco, was completed as part of the Fifth and Mission Special Use District which had that exact intention.

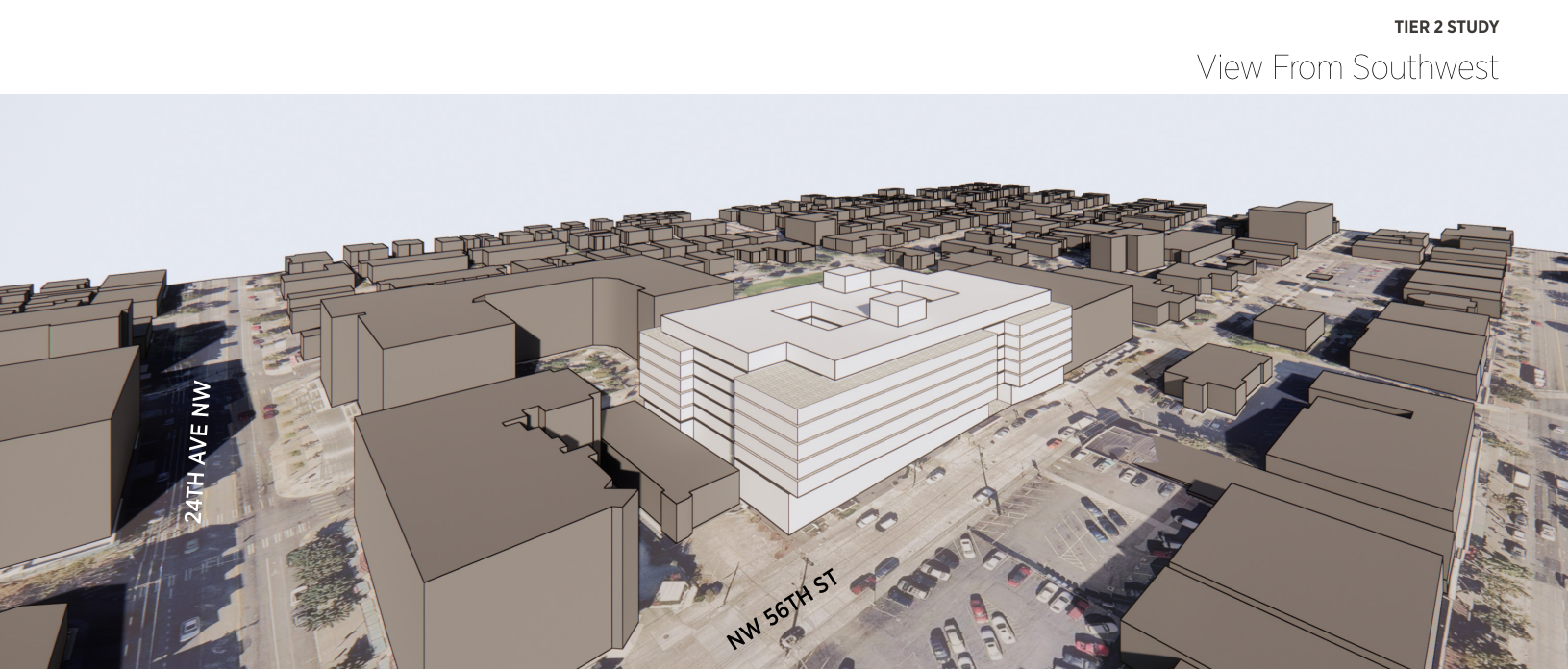

An aerial shot of The George and the surrounding Fifth and Mission Special Use District

Risks

Of course, while there is a great possibility for a large, impactful success with expansive projects like these, masterplans also come with a lot of risk for the developers that back them. Often, the biggest risk taken by developers in our environment of rapidly shifting construction and real estate markets is timing. These masterplans are for projects that can take many years, maybe even a decade, between the start of the planning process and a building’s completion, so every early decision really counts.

A thoughtless decision in the initial layout of a lot or in the design parameters that get baked into an EIR* can very easily balloon a project’s timeline. If an individual building’s design is consistent with the design guidelines studied in the masterplan’s EIR, then the building doesn’t need its own separate EIR. However, if a project deviates from what was studied in a masterplan’s EIR, there’s a chance that the building will need to conduct its own environmental review, which is a very long process. This can spiral out of control when every building needs a time-consuming modification to rectify the issue. On the other hand, well thought-out initial design documents can facilitate a smooth entitlements process, meaning that you get exactly what you expect on your project while shaving months or years off the approvals timeline, directly resulting in earlier TCOs**.

How Architects Can Help

As architects we’ve worked on complex projects like this with many development partners. We know what strategies work well and what common pitfalls to avoid. We want to ensure that complex masterplans are not more complex than they need to be.

Video: Navigating Complex Entitlements with Architect Chris Gebhardt

Working hand-in-hand with architects throughout the process to design buildings as guidelines are being developed is the best-case scenario for masterplans with complex entitlements. Your priorities become the driving force when the building designs are actively influencing the design guidelines, instead of merely reacting to them. It’s so much easier to make the case that a massing modulation requirement is overly restrictive by showing the city a beautiful non-complying building they would be happy to approve before that compliance language gets codified than after, when they and you are forced into a time-consuming mediation process. In some cases, owners have been able to use excerpts from our SD design packages as the actual “design guidelines” so they know they’re going to be allowed to build the building they want and allowing them to skip the whole process of developing generic design guidelines that could backfire. In this scenario, when the individual buildings need to be entitled its basically a rubber stamp review.

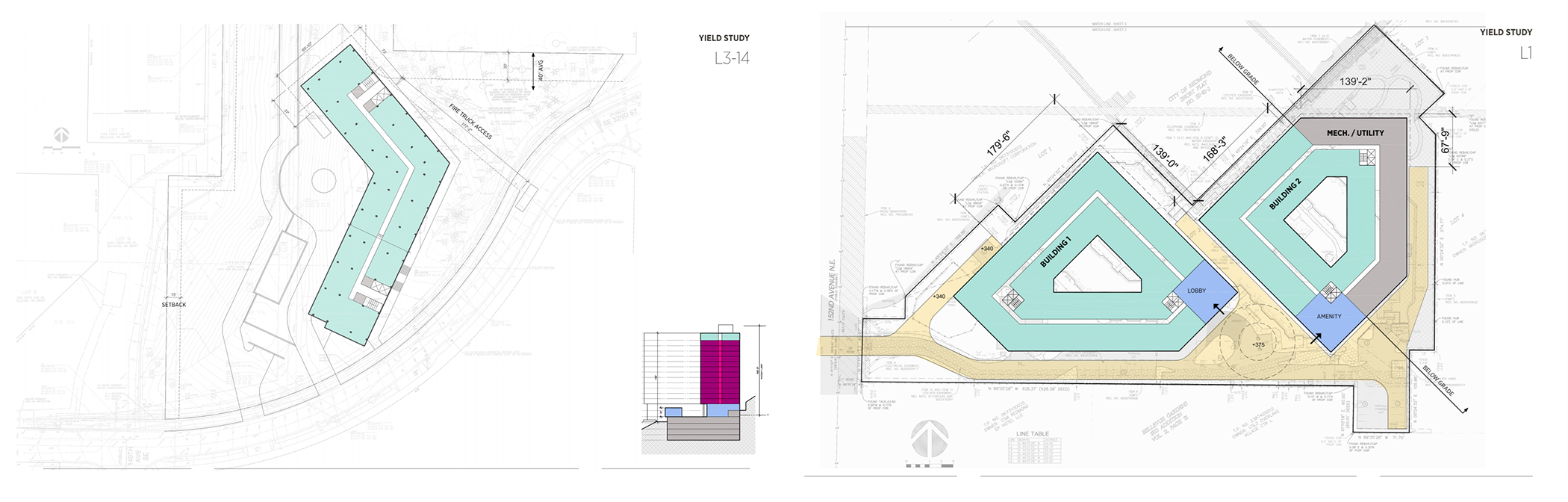

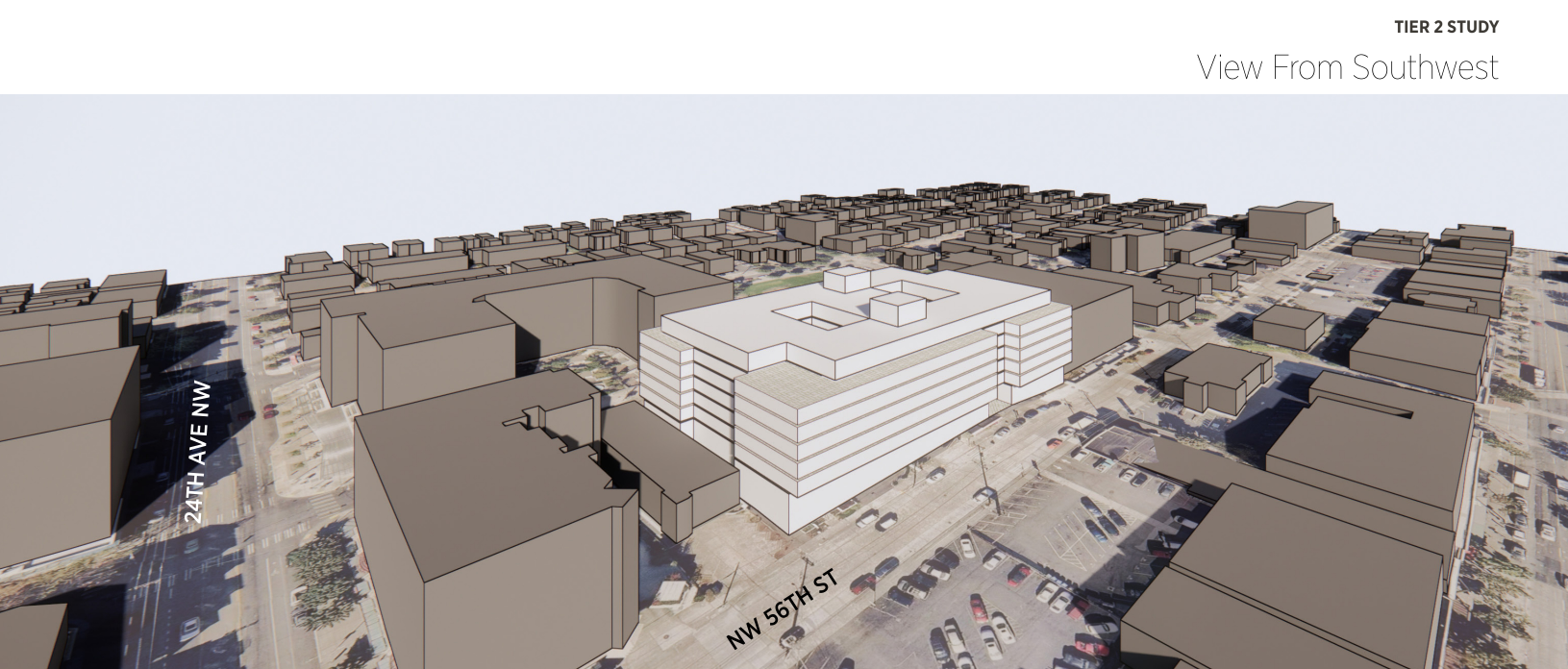

Even if the architects can’t be brought on for a whole initial design phase it can still be impactful to get them on board for occasional test fit checks, studying the lots and design standards you are considering implementing. It does not require consistent work (with associated consistent fee burn) but can be done as short studies here and there, and if you’re using the same team, they can get increasingly efficient with the studies and then translate what they’ve learned into an efficient early design phase once you get to that point. Our tier 2 feasibility study service provides a quick-yet-accurate understanding of the yield potential of a site. Typically, it includes a full zoning analysis, a zoning mass impacts table, buildable volume diagrams, and graphic site location and zoning, among other expected deliverables like simple floor area plans, an area summary, and simple massing diagrams. In the context of developing a masterplan, this template can easily be used to study the impacts of design requirements.

While it’s ideal for an architect to get involved with a project in the early planning stages, bringing on an architect at any stage means that you’ll get an expert’s input on integral elements such as lot dimensions, building heights, fire access, and building utilities.

For The George, part of the significant 5M development in a historic part of San Francisco, we were unable to join the project early on, meaning that we had to rely on other solutions to streamline the entitlements process and make the project more efficient in terms of both time and money. To create this 20-story high-rise (one of the largest housing developments in San Francisco), we implemented a combination of different strategies for navigating complex entitlements for large masterplans, resulting in a final structure that was practical and passed entitlements reviews while also still being beautiful and transcendent.

Here is a glimpse of some of the insights that might be shared by an architect who is brought into a project at a later stage, that can still help avoid the complications and delays that are commonly associated with complex entitlements and masterplans.

1. Lot Dimensions

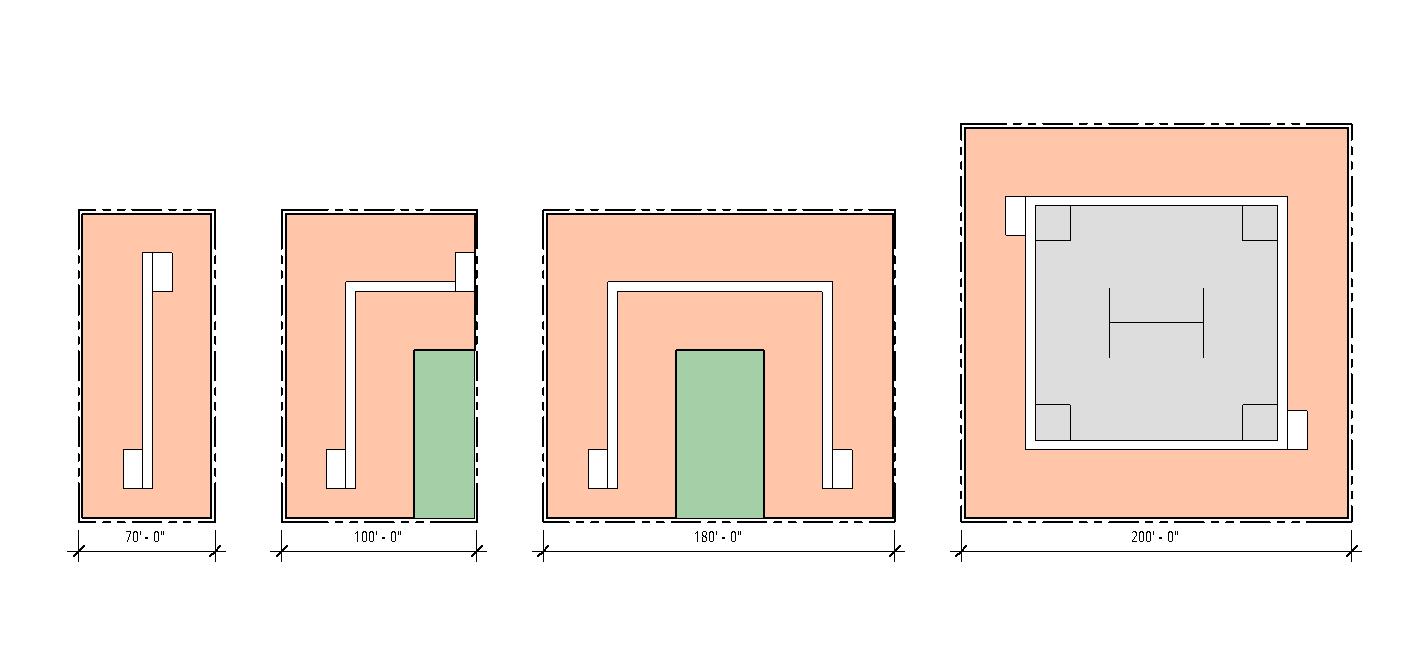

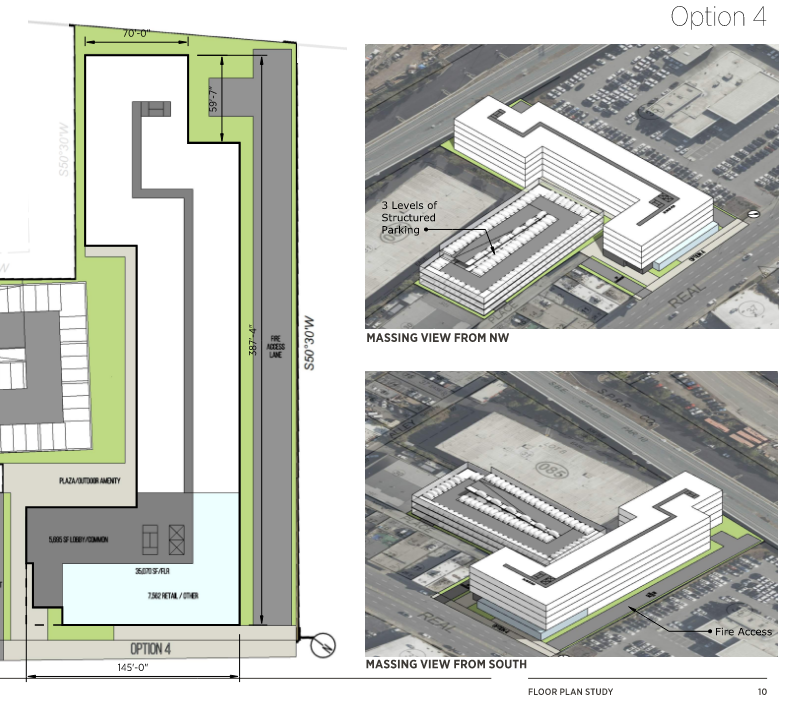

There are modules that work efficiently for different buildings and building types. In mid-rise construction, an efficient double-loaded corridor building wing is about 65 to 70 feet wide, so site dimensions smaller than that can be a serious challenge for multifamily developments. If you need on-site open space or daylighting, then that requires another 30 or 40 feet, which means you want at least 100 feet for an L-shaped building. If you want a full U-shaped building, then you’ll need 180 to 200 feet with exposure on at least three sides. For a parking wrap or “Texas Donut” style building, you’d need at least 200 feet minimum.

Minimum efficient lot dimensions

Lots with dimensions that fall between these sweet spots often lead to inefficient building layouts, such as single-loaded corridors, or they aren’t able to utilize as much of the site for rentable units as would be preferred.

2. Building Heights

Building height limits tend to be set in increments of five or ten feet, which isn’t an issue if you can keep in mind that real building heights are a bit messier than that. It’s rare. for a residential floor to actually be 10 feet high. 10′-6″ is a much more comfortable floor-to-floor height for wood-frame housing than 10′-0″ is. If there are ground-floor residential units, it’s likely that they will be raised above the sidewalk, meaning that a couple of feet need to be added to the height to account for that step-up into the building. Another couple of feet need to be added for the roof, as well, since it’s always thicker than a typical floor.

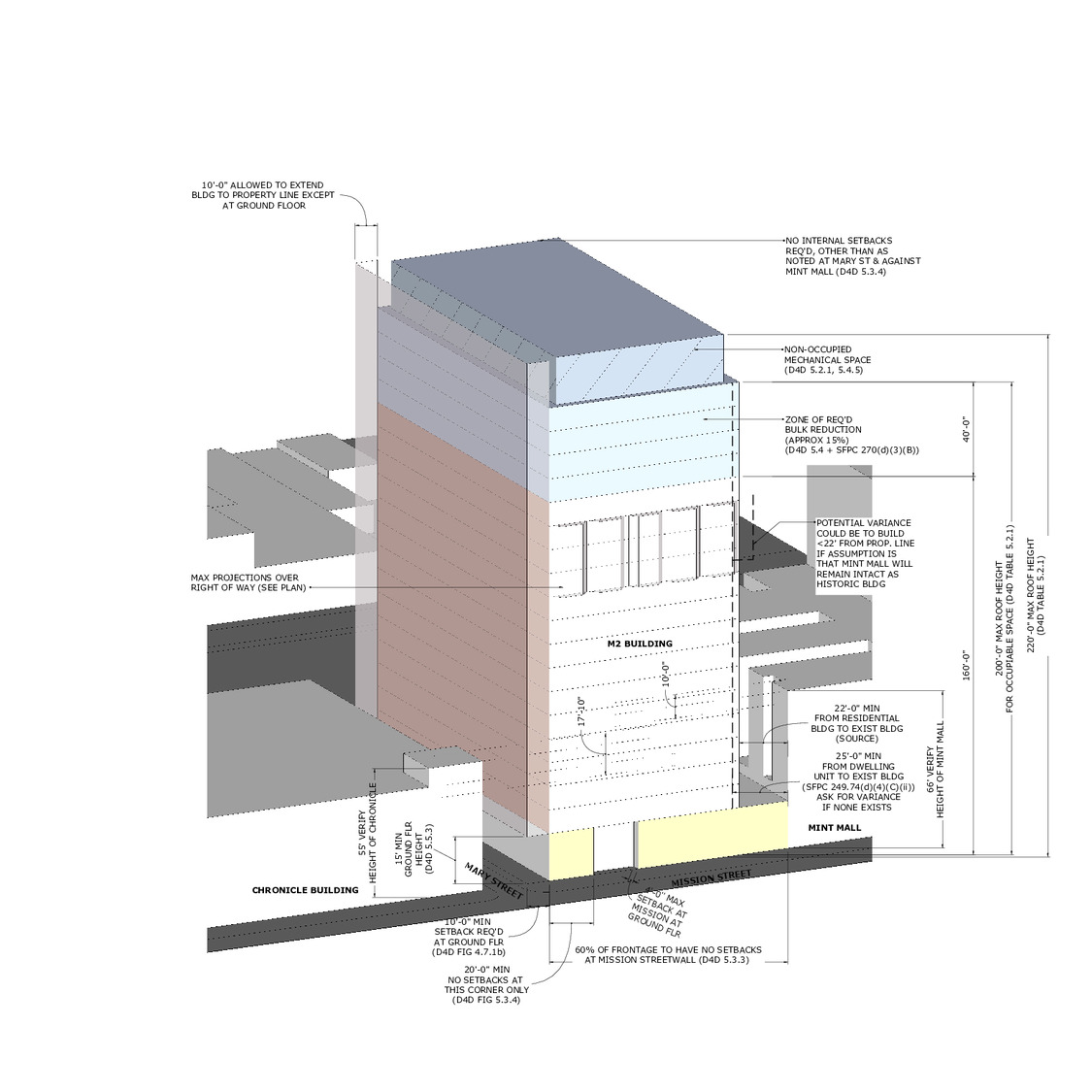

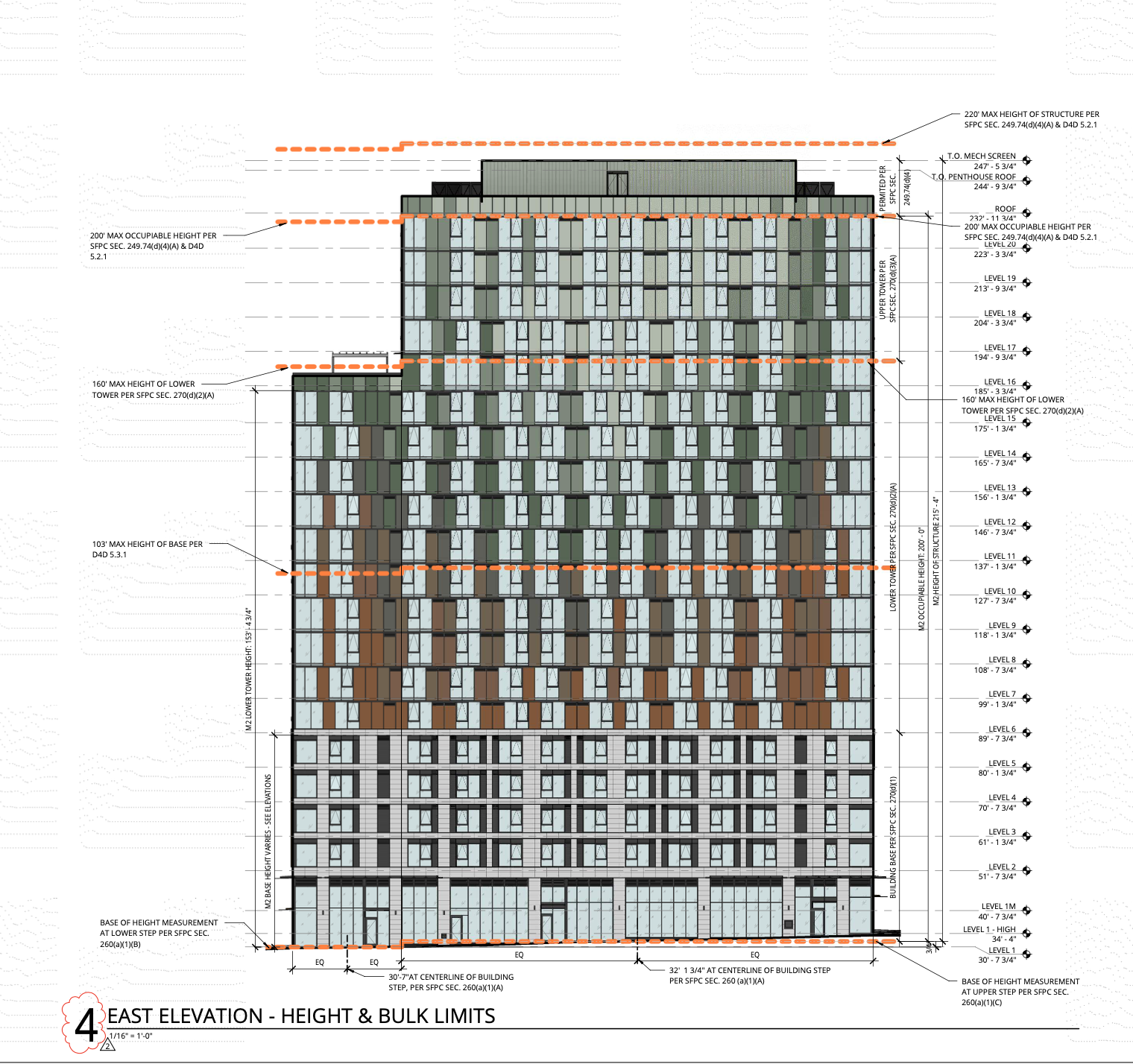

Preliminary height & bulk requirements analysis for The George’s site

While thinking about the height you want for your building, be sure to check where your jurisdiction measures the top of the building to, as some will measure to the parapet while others measure to the roof surface. You’ll need to check if elevator penthouses can be excluded, and how they address sloped sites, among other things. These nuances can really make or break the yield on a site, so it’s worth spending a little extra time thinking about the limitations of a height limit and checking all the edge cases to ensure that you can get what you want on your site.

Height limit compliance diagram for The George

It’s also important not to forget that building code limits low-rise construction to 75 feet from the lowest level of fire department access to the highest occupied floor. Anything above that falls into the more expensive high-rise territory. These heights can also influence the types of material used during construction – wood can be utilized for buildings under 75 feet, while anything above that height needs to use concrete or steel.

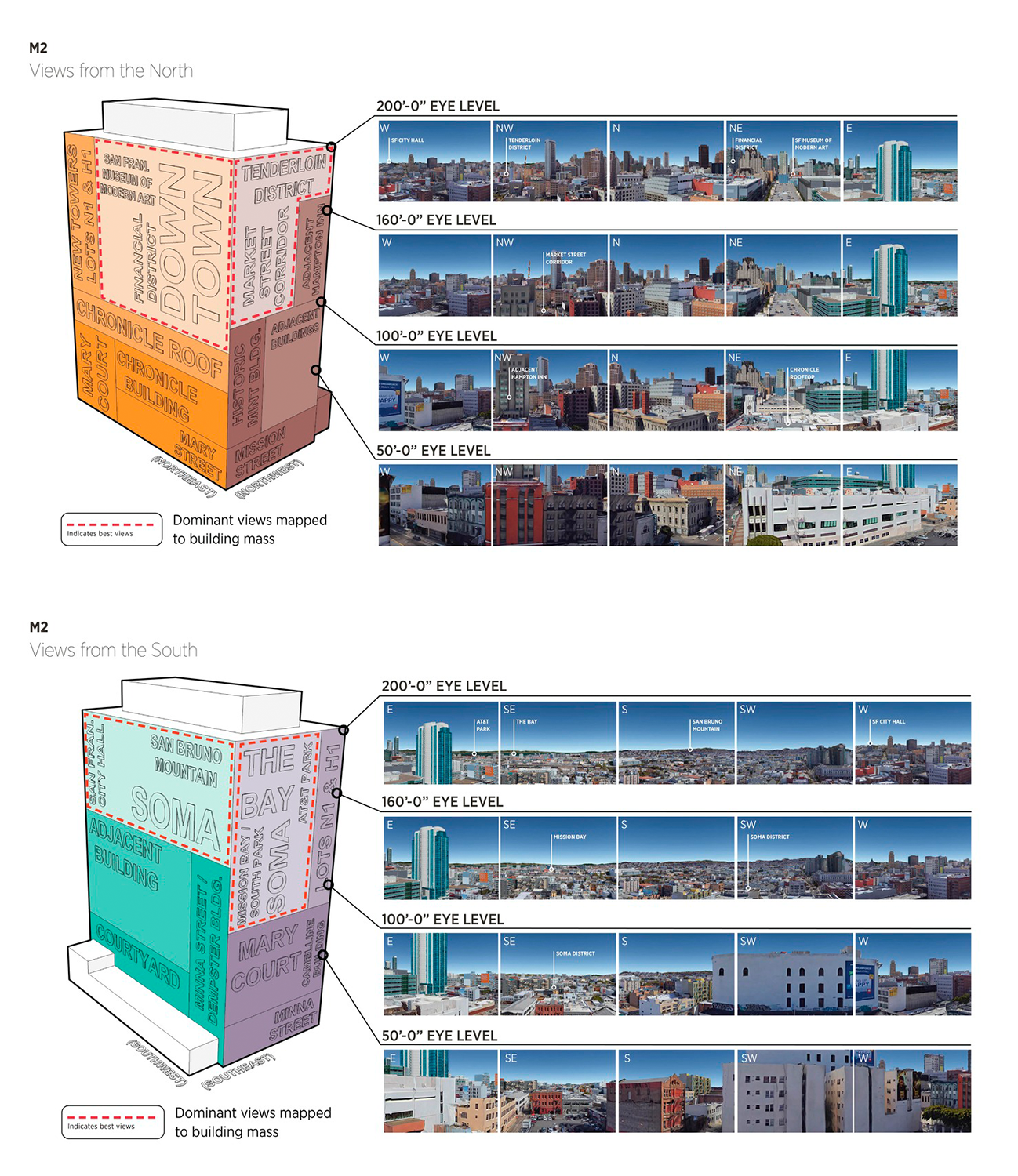

View analyses at various heights for The George

3. Fire Access

Building code states that firetrucks must be able to get close to a building, meaning that any solid masterplan needs to account for a fire access road along one or two sides of the structure. One of the real luxuries of laying out both the lots and the adjacent roads for a project is that you can make sure that fire access works from the very beginning. There’s nothing that wipes out a site’s capacity faster than needing to run a 26-foot-wide aerial apparatus access road through it – if fire roads aren’t accounted for, it will impact the size and shape of your building.

A yield study for a different project that didn’t end up penciling out due to the fire access lane that ended up being necessary

The best way to avoid this is to coordinate with local fire authorities to ensure that they have adequate access to each site. This usually means providing a 26-foot clear road along one complete side of the building, located between 15 and 30 feet from the face of the structure. With that provided, it’s a good idea to make sure that there is a point on the lot perimeter that’s within a 150-foot path from a minimum 20-foot wide apparatus access road. Easy fire access will really open up a site and increate the ability to optimize building shape for yield and efficiency, rather than fire compliance.

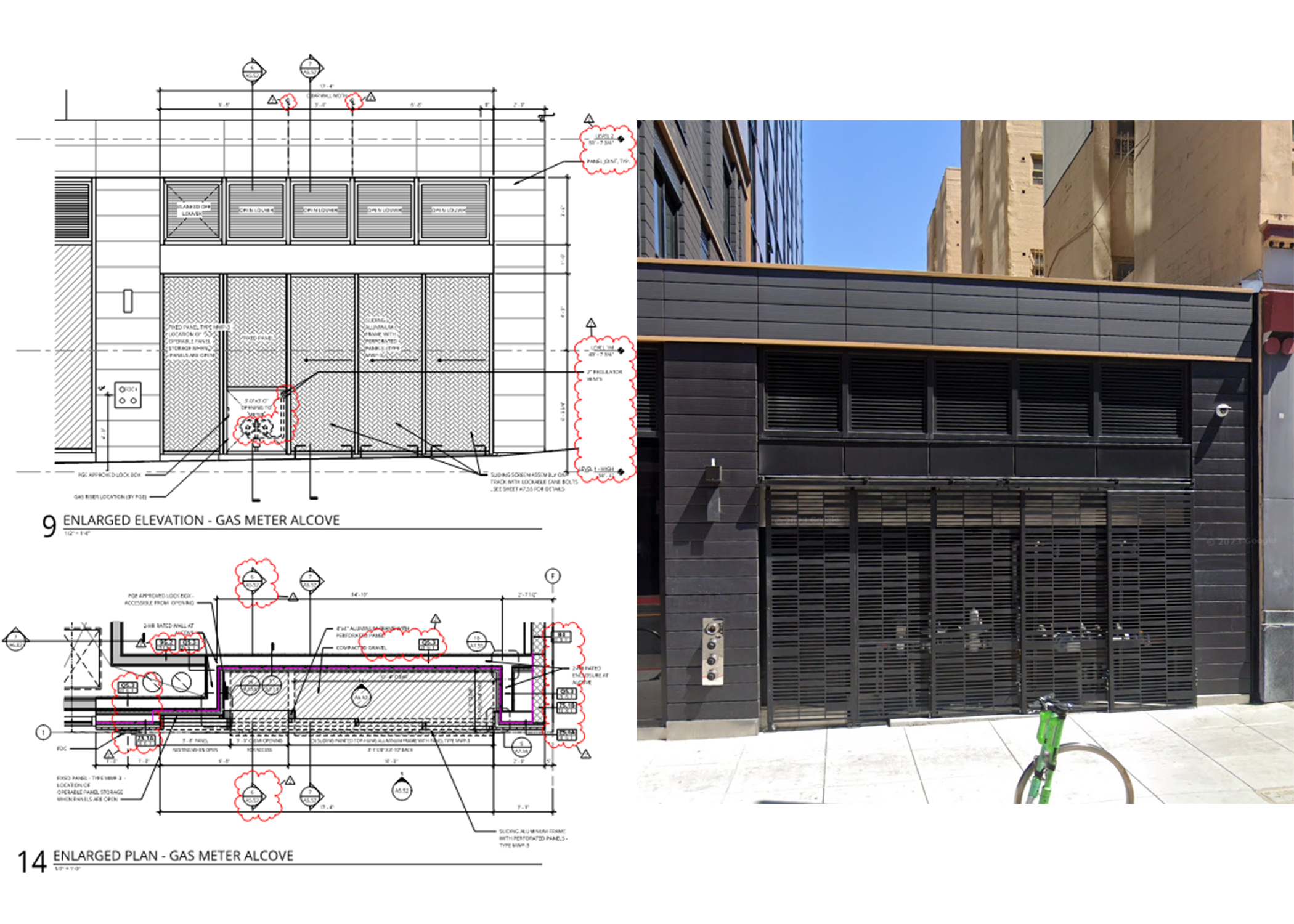

4. Building Backs / Utilities

These days, utilities in California are becoming more and more demanding about getting dedicated spaces on the perimeter of buildings, while planning departments are becoming less and less permissive about allowing those dead spaces to eat up active pedestrian frontages. Creating a hierarchy of streets in your masterplan that includes de-emphasized service roads or alleys is the best way to give each regulatory agency what they want while also providing an easy place to locate all the unattractive but necessary functions like loading docks, transformers, and other utility rooms where they won’t spoil the primary frontages you’re using to create pedestrian environments that appeal to both residential and retail tenants. Placing utility infrastructure like gas alcoves, water entry points, and other industrial rooms in locations that are not prominent in the design of a space is one solution that allows for the inclusion of these necessary considerations while allowing them to be de-emphasized. Though we do our best to incorporate these significant spaces into the overall designs of buildings, it is easier and much more cost effective to ‘hide’ them when there is a backside to the building that will not be visible to the public.

The gas meter alcove at The George

Conclusion

Though translating necessary design considerations resulting from code into something that is both practical and beautiful can be extremely challenging if you don’t get a head start with coordinating all the aspects of a project, by adhering to these tips for designing winning masterplans and considering architectural components of a building earlier in a project’s lifecycle, the overall process of working on complex masterplan projects can be streamlines and made more efficient.

*EIRs, or Environmental Impact Reports, are multi-year studies done for any big project to comply with California’s Environmental Quality Act.

**TCOs in this context are Temporary Certificates of Occupancy. They’re the first permits that allow tenants to occupy units and building owners to collect rent. It marks the transition from a building being a “construction site” to becoming a site that anyone can go inside and use. Acquiring this certificate early translates to being able to open your project up to the public and collect revenue, sooner.

Should Your Building Become Housing? Critical Considerations for Adaptive Reuse

It’s the question on every developer’s mind right now. Is adaptive reuse feasible for my building? Cost-effective? What will a housing conversion project entail?

Since 1994, Ankrom Moisan has been involved with adaptive reuse projects and housing conversions. The depth of our expertise means we have an intimate understanding of the limits and parameters of any given site – we know what it takes to transform an underperforming asset into a successful residential project.

For customized guidance through the adaptive reuse evaluation process, contact Jennifer Sobieraj Sanin, Housing Studio Design Director and residential conversion expert.

The Rule of Six

While there is no magic formula or linear ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to conversions, we have a framework that should be considered when approaching an adaptive reuse project. We call it “The Rule of Six.”

The Rule of Six outlines six key characteristics that make a project a candidate for successful conversion, and six challenges to be prepared for during the renovation process.

With this informed process, we’ve been able to get over 30 one-of-a-kind residential conversion projects under our belt.

The Six Key Characteristics for a Successful Conversion

Not every building is a good candidate for conversion. By evaluating multiple structure types and working closely with contractors on successful projects, we’ve identified six key characteristics that lead to the creation of successful, low-cost, conversions.

If a property has any of these traits – whether it’s one characteristic of all six – it might qualify as a candidate for a successful conversion.

- Class B or C Office

- 5-6 Levels, or 240′ Tall

- Envelope Operable Windows Preferred

- Walkable Location

- 12,000 Sq. Ft. Plate Minimum

- Depth to Core Not to Exceed 45′

To find out if a property makes for a good adaptive reuse project, consider conducting a feasibility study on the site.

Reach out to get started on your feasibility study today.

The Six Challenges to be Prepared For

West Coast conversions can be particularly challenging with their seismic requirements, energy codes, and jurisdictional challenges – your conversion team should be prepared for these hurdles. The solutions vary by project; contact us to see how we can solve your project’s challenges.

- Change of Use: It’s the reason we upgrade everything. The simple act of changing a building’s use from office to residential immediately triggers a ‘substantial alteration.’ This label starts all the other necessary upgrades.

- Seismic-structural Upgrades: Buildings on the West Coast must meet a certain code level to be deemed acceptable for the health, safety, and welfare of end-users. Often, this required level does not match the current code, meaning negotiations with the jurisdiction are necessary.

- Egress Stairs: Stair width is usually within the code demands for conversion candidates, but placement is what we need to evaluate. When converting to residential, it’s sometimes necessary to add a stair to the end of a corridor.

- Envelope Upgrades and Operable Windows: West Coast energy codes require negotiated upgrades with jurisdictions, as existing envelopes usually don’t meet the current codes’ energy and performance standards. Operable windows are a separate consideration. They are not needed for fresh air but are often desired by residents for their comfort.

- Systems and Services Upgrades: These upgrades often deal with mechanical and plumbing – checking main lines and infrastructure, decentralizing the system, and adding additional plumbing fixtures throughout the building to support residential housing uses.

- Rents and Financials: Determining how to compete with new build residential offerings is huge. At present, conversions cost about as much as a new build. Our job is to solve this dilemma through efficient and thoughtful design, but we need development partners to be on the same page as us, knowing where to focus to make it work.

At the outset of any conversion, we analyze each individual site and tailor our process to align with the existing elements that make it unique. Working with what you have, our designs and deliverables – plans, units, systems narratives, pricing, and jurisdictional incentives – are custom-fit.

To better understand if adaptive reuse is right for your building, get in touch with us. We can guide you through the feasibility study process.

To see how we’ve successfully converted other buildings into housing, take a look at our ‘retro residential conversion’ case study.

By Jennifer Sobieraj Sanin, Housing Studio Design Director.

Contact: +1 (206)-576-1600 | jennifers@ankrommoisan.com

Making the Future Feasible

Ankrom Moisan has offered feasibility studies as a service to existing and potential clients for decades. For those who are unfamiliar, a feasibility study helps assess the viability of a potential development on a particular property. It aims to help a real estate investor understand the future amount of revenue-generating area on a piece of land, and what a reasonable sales prices might be for that land.

Typically, the feasibility study process begins when a client, landowner, or broker reaches out to us. We usually start with a site analysis, to get an idea of the average unit size and parking ratio, and then conduct a ‘fit test.’ That fit test quickly and efficiently diagrams potential development outcomes that could be realized on the land parcel. When conducting a fit test, we look at the site’s zoning code, relevant building code, physical site characteristics, visible utilities, site context, and building typology constraints. These constraints are often related to building uses, building type, height and size, or the amount of parking required. For example, a housing-use structure has much different parameters than an office-use one. Further, a ‘Stick-Frame Wood’ building typology will yield something quite different than Cross Laminated Timber or Concrete.

Examples of a feasibility yield study.

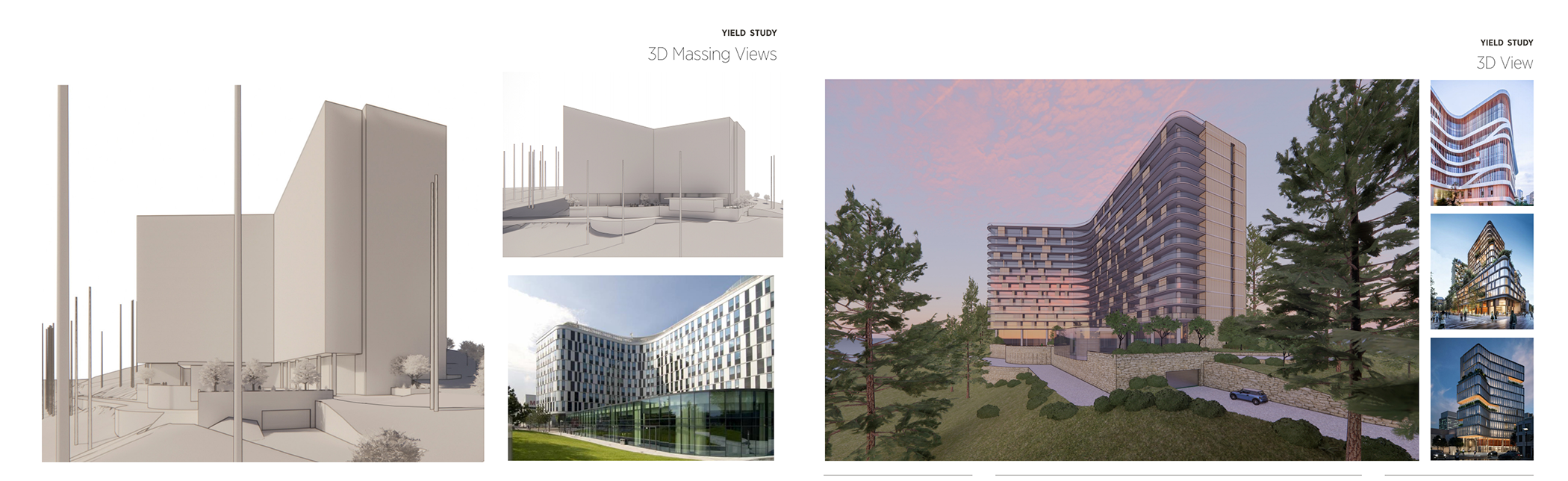

If desired, we can go further and analyze architectural outcomes that consider preliminary ideas about building design and character. Sometimes, a client will provide their own constraints or parameters, like a more detailed unit type and amenity program. Renderings of varied detail may be added to this process to help visualize a proposed project idea; they are useful to illustrate the early-stage potential of development ideas to a wider audience.

Example of a Tier 2 Feasibility Study Perspective View.

We often provide our clients with multiple (and sometimes contrasting) design ideas. By discussing the advantages and drawbacks of each idea, we reach a point of mutual understanding with our clients and can begin to fine-tune their vision.

Animated early visioning sketch for a multifamily housing urban land parcel assessment.

It is all about leveraging future architectural solutions to effectively utilize what a site has to offer. We are constantly seeking improvement in this process and are regularly evaluating methods to do so. From a basic ‘back-of-the-napkin and a calculator’ approach to a deeper architectural examination informed by years of design experience, or even the use of Artificial Intelligence software that can automate metric evaluation of a site, we consider all possibilities and methods of maximizing a project’s design according to client desires and site parameters.

3D Massing Views and renderings conducted for a Tier Three feasibility study.

Through this process, we give clients, landowners, and brokers meaningful guidance towards the value of their land parcel. This process is especially helpful for people interested in working with Ankrom Moisan for the first time, as a feasibility study is an uncomplicated way for prospective clients to get to know us and learn how we work. It is a great opportunity to see if we work well together.

We have a vast resumé of work and pull from a wide range of past experiences with different building types – everything from tall to small, across a variety of uses (retail, hotel, office, hospitality, housing, etc.). We enjoy this work as it is an essential part of our process. We enjoy offering feasibility study services that share our expertise with longtime and prospective clients, landowners, and brokers alike, showing exactly why Ankrom Moisan is a valued design partner.

By Jason Roberts, Managing Design Principal, Bronson Graff, Associate Principal, and Jack Cochran, Marketing Coordinator.