Research shows that homelessness and the mental health crisis are interconnected issues.

“The relationship between mental health disorders and homelessness is complex and bi-directional: mental health disorders may lead to situations that result in homelessness, or homelessness may be a stressor contributing to the development or worsening of mental health disorder symptoms. Homelessness is affected by a complex interplay of social determinants of health, including poor social and economic conditions. Homelessness is also associated with health inequalities, including higher morbidity, shorter life expectancy, and higher usage of health services.” (JAMA Psychiatry)

Because of this connection, there is an increased need for treatment centers that leverage both our healthcare and affordable housing expertise. Stable supportive housing, primary care, crisis stabilization, and mental healthcare alongside treatment of substance use disorders as a holistic built environment can treat all aspects of these tangled issues than need support from various avenues to treat the whole person. Ankrom Moisan is proud to work with forward-thinking organizations who plan to think outside the traditional models of healthcare and move all these services under one roof.

Behavioral Health

Serving the full spectrum of care, behavioral health projects address outpatient therapy, inpatient treatment, supportive housing, addiction recovery, and everything in between. They’re spaces where healing begins, continues, and is sustained.

To achieve these comprehensive centers of care, we take a trauma-informed, human-centered approach, prioritizing safety, serenity, and connection. Every project is built around respect for the people who heal, the people who care, and the communities they serve.

Across all our behavioral health projects, we focus on design strategies that support dignity, healing, and community. Some consistent solutions include using durable materials that can stand up to high-use environments, incorporating natural wood or wood-look finishes to add warmth, added acoustical wall or ceiling treatments that are design features, access to daylight and Biophilic connections to nature, and creating gathering spaces where residents can connect.

Some recent work that exemplifies our understanding of behavioral health needs and our commitment to creating environments that reduce stigma and promote wellness include:

Alameda Medical Respite and Primary Care

Alameda Point Collaborative (APC) saw a need within their community and realized that they needed to provide multiple services within one building and as a whole campus adjacent Crab Cove in Alameda, California. Set to open in March of 2026, the Alameda Medical Respite and Primary Care building blends healthcare with stable respite care, providing a facility that integrates trauma-informed care in a dignified environment, addressing the complex health needs of those experiencing homelessness in Alameda County. Dedicated to creating a 50-bed medical respite program, an on-site primary care clinic, donation center, and a client resource center to help the most vulnerable get the help they need to heal and offer the services to help beyond their immediate medical needs.

Rendering of Alameda Point Collaborative

By integrating on-site healthcare with respite care beds, the Wellness Center offers a holistic approach to health, from primary care to end-of-life services. It creates a community that nurtures long-term, healthy change by ensuring access to quality healthcare, access to stable housing through the resource center, and comprehensive support services, not only providing physical care, but also fostering a sense of belonging and dignity for the residents as they recover.

Green planters were introduced to the exterior of upper windows, meaning that even those residents confined to their rooms could still see life growing just beyond the glass of their windowpanes, encouraging both hope and resiliency as they traverse the road to recovery.

Blackburn Center

Opened in 2019, Central City Concern (CCC)’s Blackburn Center in Portland, Oregon, represents a groundbreaking approach to supportive housing. Designed to integrate modern housing with in-house clinical services, it stands out as one of only five centers in North America that combines healthcare, permanent supportive housing, transitional housing, pharmacy, urgent care, respite care, retail, and palliative care for individuals experiencing homelessness.

CCC Blackburn Center

Each level of the Blackburn Center’s six levels represents a different step on the resident’s journey to healing, from clinical treatment on the ground floor to independent living on the top. Integrating housing, supportive services, and clinical services under a single roof makes healing more accessible and more effective by creating a community for the residents to not just survive, but to find their own pathway to thrive.

We intentionally created two very different types of community spaces within the Blackburn Center – a quieter lounge along the residential street for reading and small group gathering, and a more active hub above a bustling commercial street, designed for cooking and sharing large meals, watching TV, and playing games. Both spaces support different needs and approaches to community, recognizing that recovery isn’t one-size-fits-all.

Another shared space, a generous outdoor terrace at the upper third level for respite care, is integrated into the programming of connecting to the outdoors as part of the palliative and respite care programs, meaning that residents don’t have to travel far to step outside for fresh air and daylight.

Compass Health Marc Healing Center

With a ribbon-cutting ceremony taking place in September 2025, the Compass Health Marc Healing Center in Everett, Washington, offers a holistic care model that removes common barriers to seeking help and provides a path toward stabilized living for those struggling with mental health. Tailored to provide familiarity and comfort, it serves a wide range of people in different stages of their mental health and crisis recovery journeys.

Compass Health Marc Healing Center

Upper-level outdoor spaces were designed with screening from the level above to provide privacy for residents while maintaining access to the open sky and natural light. Tall, solid-glass railings were included to prevent residents from climbing over, while still allowing them to look out onto other nearby green-roof spaces. Habitat plantings were added to those green-roof spaces to attract insects and birds, encouraging pollination and strengthening Compass Health Marc Healing Center’s commitment to environmental sustainability, and connection to the natural world.

Using materials, massing, and connections to natural spaces, the Compass Health Marc Healing Center aims to change the perception of what behavioral health facilities look like by making recovery spaces feel less institutional and more like a home. It’s a place of warmth and comfort.

As Ankrom Moisan continues to strengthen its behavioral health work with impactful buildings like Alameda, Blackburn, and Compass Health, we take the lessons learned from each project with us, bringing new insights, as well as design solutions, to future work, providing care and supportive pathways to recovery and healing to those who need it.

Approaches to the Design Process that Can Help Push Multifamily Projects Toward Construction

As nearly a billion dollars of bond money was invested in affordable housing projects in the Portland-metro area, architects are finding paths to success. Commenting on what jurisdictions can do to encourage housing development, Don Sowieja, Principal, shares his thoughts on how different approaches to the design process can help push multifamily projects toward construction.

“The city of Portland has taken major steps to encourage development,” Don said. One of these steps was consolidating permitting functions into a single bureau: Portland Permitting & Development. “Prior to that shift in policy organization, you might expect three to four months before you go your first round of plan review,” he continued, adding that it now takes around six weeks.

According to Don, when it comes to overall timeline for a project, the design process is critical.

Simplify the Design Process

“One of the things we’ve found is to keep it simple,” he said.

“Keeping a basic layout and overall composition allows a project to move through the process more quickly,” Don claimed. “Oftentimes a proposal’s details may be unclear to city staffers, so it’s important to keep an open line of dialogue with them to navigate the approval process.”

“The simpler the design, the simpler the compliance,” he said. For multifamily housing, unit size and type matter. “If you have three unit types – studios, one bedroom, and two bedrooms – and you have one of each of those unit plans, that’s as easy as it gets for the city to understand, as well as for the developer to demonstrate compliance,” Don said.

For projects subject to design review, Don encourages teams to know the rules and follow them. “It’s right there on the page,” he said. “Reading and doing what it says is the best way to move quickly through a subjective process.”

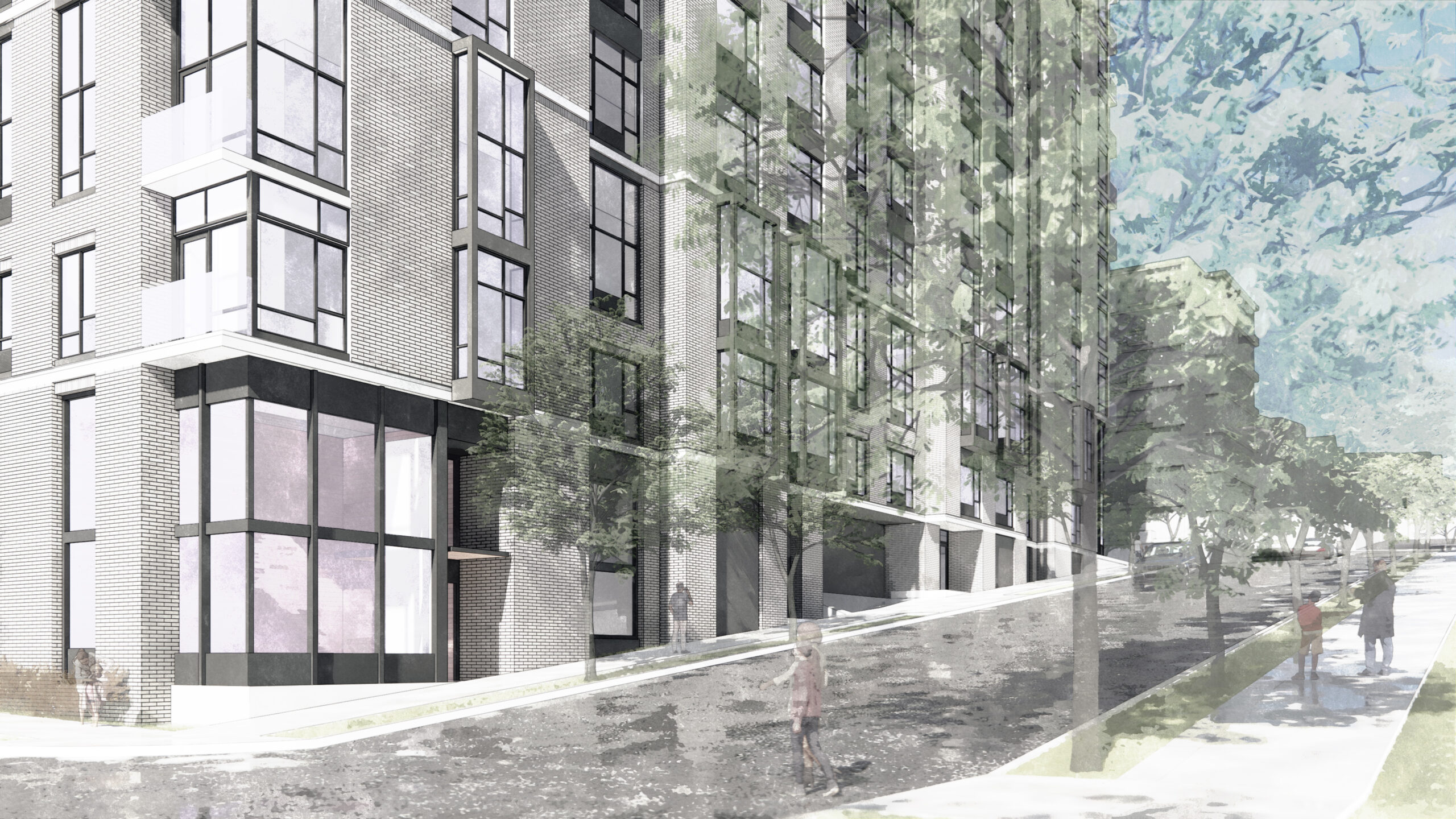

Project rendering of Pepsi Phase B, an inclusionary housing project in Portland.

Embrace Inclusionary Housing

Although inclusionary housing is relatively new to Portland, many cities on the West Coast have similar criteria. In Portland, inclusionary housing requires all residential buildings proposing 20 or more new units to provide a percentage of them at rents or sale prices affordable to households at 80 percent of the median family income or below.

“Development teams should embrace the fact that it is a requirement for multifamily projects,” Don said. “While there was some concern at the outset of this new requirement, most of the development community has figured out that it has a financial and organizational impact.”

According to Don, demand for multifamily projects has declined in the past 2.5 years, following a roller coaster of economic cycles, including the COVID-19 pandemic, inflation and interest rate increases. However, that has begun to change in 2025.

“The design side is really picking up,” he said. “That takes a while to translate into construction starts, and construction is the big money and the larger economic driver.”

Hopefully, once the industry’s efforts shift toward construction, we will see more architects working with jurisdictions to simplify or streamline the design process to increase housing, and more developments being made to meet the need for affordable housing throughout our cities.

How Jurisdictions can Encourage Housing Development

When it comes to encouraging the development of housing projects, there are a handful of things that jurisdictions can do to support architects and designers, streamlining the process of design and construction from start to finish.

Our projects outside of Seattle, Canopy and Modera Shoreline, benefitted from an accelerated project timeline, a result of the City of Shoreline’s collaborative approach to streamlining the design review process.

Project rendering of Modera Main Street

In the last 10 years as urban affordability and quality of life have become issues to residents, developers and investors have looked to new submarkets for development. Sharing its southern boundary with Seattle, the city of Shoreline has been recognized as one of the area’s fastest-growing residential hubs.

After listening to developers, the city set about enhancing its portals, attracting brand retailers, planning for future TODs, codifying development incentives around sustainability, and streamlining their entitlement and permitting processes. Amidst the challenging economic times of the last two years, three developments alone – Shea’s Canopy and Verdant, and Mill Creek’s Modera Shoreline developments – have created more than 1500 units, demonstrating that a jurisdiction’s focus on encouraging development can have transformative impacts.

Canopy

A motivated jurisdiction can work with the development community to create the vibrant city desired by its constituents. There are several ways this may come to fruition.

Reducing Permitting Timelines

Bypassing Design Review and MUP milestones could yield significant time and cost savings on project delivery, expediting the approval process and speeding up time to construction.

In 2023, the Seattle City Council amended the land use code to make two important changes to the design review program aimed at encouraging additional low-income housing.

The first change permanently exempts low-income housing projects from the Design Review program.

The second change provides a new Design Review exemption for projects that meet Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) requirements by providing units on site via the Performance Option under the Land Use Code.

Due to this change, projects that opt into the Performance Option can skip MUP and Design Review and proceed directly to Building Permit where land use code compliance will be evaluated concurrently with other review subjects.

The impact of this shift is an accelerated timeline for projects to go from design to construction, and as a result, an increase in the number of housing projects being made.

Typically, the design review board can take anywhere between three to nine months to approve a project. During this process there are application fees to be paid by the applicant, as well as other payments made to parties such as land use attorneys who determine jurisdiction or design professionals who prepare and present the information to the review board.

Reducing the permitting approval and design review timeline for a single building translates to more time that can be spent on additional housing complexes, boosting the total amount of available housing in Seattle. It also means less money is spent on a project overall through the extra costs associated with presenting a project to the design review board.

This is just one example of how bypassing Design Review and MUP milestones could yield significant time and cost savings on project delivery. A full synopsis of the impact of reduced permitting timelines can be found here.

Lowering Impact Fees

Impact fees – also called system development charges in some places, like Portland – are the method cities use to collect funds that expand or provide infrastructure to support developments that are going through the permitting process.

These fees cover everything from sewers and transportation to parks and schools and are used to either fund the construction of those services, or the maintenance and expansion of existing infrastructure. Essentially, they’re a city’s way of generating revenue to maintain the services and infrastructure that are needed for a project that is being built.

Based on a per-unit cost, impact fees, along with review and inspection costs, can end up costing a lot more than a simple permit review fee.

To encourage more developments, impact fees can be reduced or lowered. Recently, the city of Portland completely waved those charges until 2028, making it both cheaper and easier to initiate new construction developments within the city. The impact is so large that some projects currently in development would not be able to move forward at all, if it weren’t for the Portland SDC moratorium.

Project rendering for Sandy Pine

Clarifying Code Language

The Portland City Council temporarily lifted restrictions on building heights for housing projects in specific planned districts at the beginning of 2025, a decision that will remain in effect until 2032. On top of changes to code language surrounding building heights, there were also adjustments to minimum lot sizes on single-family dwelling lots.

“These amendments will help spur development to increase housing density, use land more efficiently, and create more affordability,” said Don Sowieja, Principal. “This limitation on height within the urban growth boundary for development has been very frustrating for developers. Hearing about this adjustment opportunity is a tremendous step in the right direction.”

Another somewhat recent code change made by the International Code Council provided significant updates to accessibility clearances, based on a study of wheelchair users. While the overall impact of the code change on buildings was modest/minimal, only expanding a few rooms by a few inches, the impact on impacted users was immense.

From a designer’s perspective, code changes can lead to added complexity, especially for considerations like accessibility. However, by clarifying the language around some of these codes, the design and construction process can be simplified and streamlined, leading to quicker project completion and more housing development overall.

For example, the city of Shoreline provides the Deep Green Incentive Program, which is an opportunity for development to meet certain sustainable development and construction certifications. If met, the city provides developers with increased flexibility regarding development code criteria, such as allowing additional building height, reduced parking requirements, and other substantial cost or yield impacts. Additionally, this incentive program allows jurisdictions to provide preferential treatment during the building permitting review process, fast-tracking approval and construction.

Extending Permit Life Before Expiration

Every jurisdiction has time limits for the permit review process. If there is no movement, a permit can expire, causing the project to have to restart the permitting process, adding additional costs and a prolonged timeline for a project to reach completion.

For both the city as well as developers, it’s important to keep a timeframe on project development, since it helps people plan for future projects. For example, financial transactions like loans only take place once a permit is approved. Since loan repayments need to be budgeted out over time, having that timeline shifted can obviously throw a wrench in any pre-decided plans.

Issued permits also have lifespans. Drawing them out is one way to prevent permits from expiring before a project begins construction, leading to more completed projects overall.

Jurisdictions have realized that there’s a benefit to keeping the development community engaged throughout the permit review process. Desiring to keep people involved, rather than pushing them out, jurisdictions are reaching out to applicants, offering permit extensions if formally requested.

With that change, permits can sit for longer periods of time before they have to secure/receive funding. These longer pauses come with the hope that conditions will soon shift in favor of developers, leading to more developments.

Moreover, as time passes, code and design review criteria change. Essentially, by extending permit life beyond expiration, the efforts of going through the permitting process are retained, and developments are encouraged, rather than given hoops to jump through. If permits last longer, these projects have the potential to save time and money by avoiding being re-tooled to pass review again if a previous permit expired.

All in all, these four examples of incentivizing construction and flexibility in the design review process are excellent options for jurisdictions to take advantage of in order to encourage new building developments.

Vet Clinic Expertise

Veterinary clinics are a unique project type. Blending elements of healthcare and office projects – and even retail and hospitality – they fall somewhere between all four project types, designed for both people and pets. As such, there are some special considerations that go into accommodating staff as well as the animals that receive treatment in those projects.

Most of the vet clinics we have worked on have been first tenant improvement (TI) renovations, meaning they are located in new buildings with empty commercial space on the ground floor. To accommodate the needs of both veterinary staff and the animals they treat, these spaces are renovated to include a clear separation between the front lobby waiting area and the back-clinic rooms where pets are treated by veterinary staff.

Ankrom Moisan’s veterinary work in California started with a project in the San Francisco Bay. A later project in the same area – the SOMA Animal Hospital in Mission Bay – was also the first foray into vet clinics for one of our clients.

SOMA Animal Hospital, Mission Bay

Setting the standard for all future veterinary clinic work, Mission Bay was a collaborative effort between us and our client. To ensure their flagship location effectively represented their vision for their brand, they provided 3D renderings that detailed the schematic design and layout of the interior spaces.

Considering that staff workflow is the most important part of a veterinary clinic, it was vital that we designed a smooth, easy path from the reception lobby to the exam and treatment rooms in the back, with ample additional support spaces. To effectively deliver this, the client partnered with Doctors of Veterinary Medicine, aligning on the essential needs of a vet clinic and coordinating how best to support those needs through design.

The building itself doesn’t have a typical rectangular layout. Located on the intersection of two busy thoroughfares, Mission Bay embraces the pointy corner it’s situated on, leading to a unique vantage point from outside of the building. Breaking down visual barriers in an inviting way, we used storefront glazing all around the windows to frame the interior spaces, allowing pet owners and passers-by to view the treatment rooms in the back of the clinic from the street.

Inside, we picked the finishes, paint colors, and did some of the case work detailing in the lobby, like the use of wood and the circular aperture window behind the reception desk that would become a standard in later projects with the client.

After creating Mission Bay as the flagship standard for our client, we were told that they appreciated the speed we brought the project from the planning stage to the very end of obtaining a building permit. “They liked how we handled the permitting process,” said Technical Designer Sookhee Kim. “Our prior experience with planning in the Mission Bay area made the entire process much easier for them.”

The speed and efficiency of our design process was a determining factor in completing two more similarly scoped veterinary clinics; North Hills Animal Hospital in Muirlands, and Promenade Veterinary Hospital in Long Beach.

Promenade Veterinary Hospital, Long Beach

There were some interesting challenges with the Promenade Veterinary Hospital in Long Beach, stemming from the base building still wrapping up construction as we became involved. The 3,300 sq. ft. space was one of the larger TI renovations we had done for a vet clinic, so coordinating with both the client and their landlord on scope responsibility for our TI permit was a large part of the process. Navigating active permits for the base building was challenging, but getting to the other side and accomplishing our goals for the project was very rewarding.

North Hills Animal Hospital in Muirlands, on the other hand, was very straightforward, with minimal challenges or delays to the project.

The retail-like front reception desk draws clients in through a clean aesthetic and hospitality-inspired amenities, like comfortable benches and a beverage station, giving way to the back-of house staff areas where the animal patients are treated.

Lockable doors separate both client-access spaces like the reception lobby from the rest of the clinic where technical staff operate, as well as the kennels. It was important to ensure that all of the animals treated by veterinary staff stay enclosed in the kennel area should they manage to get out of their individual cages.

There is an abundance of space in the back staff area – a commitment to keeping cats and dogs separate necessitates two waiting room holding areas, as well as two exam rooms. Naturally, the one designed for dogs is larger than the one for cats.

Durable, hygienic finishes were selected to facilitate and simplify long-term maintenance, while acoustical panels were used to dampen sound from within the kennels where canine patients await treatment.

North Hills Animal Hospital in Muirlands

Since the clinic doesn’t offer overnight stays or treatment, there are about 6 exam rooms and 10 kennels for each location, allowing staff to maximize the number of pets they treat daily.

It’s an efficient, streamlined design that supports everyone involved, from the client and veterinary staff to the pets and their humans. Having perfected it early on with Mission Bay, thanks to our attentive and collaborative process, means that we are able to replicate that success in other veterinary clinics.

Bridging the Belonging Gap

As student populations grow and on-campus housing remains limited, off-campus housing has become a critical part of the higher education experience. According to Propmodo, the demand for student housing greatly exceeds supply at many universities, making the asset class an unlikely real estate kingmaker over the past two decades. But this growing reliance has brought on new challenges.

While the first-year dorm experience is often rich in social interaction and university programming, the transition off campus can come with a steep decline in connection, support, and engagement. A column in The Daily Gamecock, the University of South Carolina’s student newspaper, put it plainly: “Off-campus housing can be isolating.” When students move off campus, they risk losing the daily rhythms and casual relationships that make college life feel cohesive. This raises a fundamental question for developers and designers alike: How can we ensure off-campus housing supports, not undermines, a student’s experience and well-being?

Putting Connection First in Off-Campus Housing Design

The best off-campus housing doesn’t just provide a place to live, it creates the conditions for connection. At VERVE West Lafayette, developed by Subtext near Purdue University, that philosophy takes center stage. Every detail of the building reflects Subtext’s broader “Unlonely Mission,” a commitment visible across other recent developments in Bloomington, Boise, and Columbus. All elements of the project are shaped by a singular mission: to unlonely student life. This shows up not just in the operations, but in the physical spaces themselves.

Verve West Lafayette

From the moment residents arrive, they’re greeted by a friendly team member at a vibrant leasing bar that doubles as a coffee spot by day and transforms into a social lounge by night. Upstairs, amenities include wellness-forward features like a yoga studio, sauna, and meditation spaces that prioritize mental health without feeling clinical. A bold design move, like a swirling slide connecting two floors, adds a touch of playfulness and sparks spontaneous interaction among residents.

There’s also an intentional balance between private and public. Study pods provide a quiet retreat, while common areas offer room for collaboration and friendship. Local design cues, from materials to murals, tie the space to the community to help students feel rooted in both place and purpose. And with a walkable location just minutes from Purdue’s campus, VERVE keeps students close to the heart of university life, even when they live beyond its footprint.

Design Strategies to Build Belonging Off-Campus

Creating a sense of belonging is essential for student success and well-being, especially in off-campus housing where students can feel socially and physically disconnected. Design plays a pivotal role in bridging this gap by encouraging interaction and fostering inclusive communities. Layered communal spaces like study lounges, community kitchens, maker spaces, fitness areas, and rooftop terraces support both structured and sporadic engagement. Semi-private “threshold” areas, such as shared entryways, floor lounges, or front porches, can facilitate passive interactions and foster the formation of micro-communities.

Verve Bloomington

Attention to scale and proximity is also essential. Breaking down large buildings into smaller “neighborhoods,” for instance, clusters of units sharing a lounge or “pods” with common amenities, helps cultivate a more intimate residential experience. Circulation spaces should be designed to encourage visibility and activity through features like open stairwells, transparent walls, and generous natural light.

Additionally, inclusion must be embedded from the start. Universal design features, like all-gender restrooms, multi-faith meditation rooms, and accessible layouts, signal that every student is welcome. But belonging also comes from the process. Early engagement through participatory design workshops, such as collaborative charrettes that use storyboarding, spatial mapping, or card-sorting exercises, can reveal latent needs and values.

Beyond the initial phases, ongoing feedback loops, through student advisory panels or milestone surveys, ensure that evolving expectations are acknowledged. Post-occupancy evaluations offer valuable insight into what worked, what didn’t, and what students wish had been included, providing direction for future projects. Partnerships with Student Affairs can surface less-visible insights, especially for underrepresented grounds, and collaborating with departments such as housing, DEI offices, or cultural centers helps ensure the design reflects the full spectrum of student experiences.

Verve Boise

The building’s location and its access to campus and neighborhood matter just as much. Well-lit walking paths, secure bike infrastructure, and proximity to transit support easy movement, while ground-floor retail or community-facing programming can integrate student housing into the fabric of the neighborhood. Visual and programmatic links to campus, views of landmarks, spaces for student orgs, and campus-branded graphics reinforce psychological connectivity. Ultimately, off-campus housing that offers informal third spaces, integrates wellness through design, and supports events like shared meals or club meetings becomes more than a place to live – it becomes a platform for unity, identity, and student growth.

A Call to Align

For the growing number of students living off campus, the line between inclusion and isolation often comes down to how their housing is designed. Developers, designers, and campus leaders must work together to meet students where they are, both physically, socially, and emotionally.

Off-campus doesn’t have to mean disconnected. In fact, with intentional design, it can be a powerful extension of campus life. By aligning priorities and centering connection, we can ensure that student housing continues to support, not interrupt, a student’s college journey.