The design process for healthcare spaces is multi-layered, spanning months to years, and involving numerous stakeholders. Healthcare Project Manager Greg Salandi is the first to admit that there are many areas where it can be improved. It isn’t unheard of for there to be hiccups when bringing a project to life, however, in the case of medical spaces, having to repeatedly go back to the drawing board to accommodate new information, changes in stakeholders, or evolving technologies can delay the opening of a project and waste both time and money. For the Healthcare sector, specifically, challenges like this can diminish or delay the much-needed care that patients in our communities seek.

To explain the current design process, where issues arise, and what Ankrom Moisan is doing to streamline early design and improve the process of designing healthcare spaces, Greg and Healthcare Principal-in-Charge Hao Duong sat down to discuss efficiency concepts in the design of healthcare spaces for better overall project delivery.

Greg and Hao in Ankrom Moisan’s Seattle office.

Current Process

The current design process employed by Ankrom Moisan’s healthcare team (AMHC) begins with a “dance of coordination with client stakeholders and the design mechanical, electrical, and plumbing (MEP) consultants as it pertains to equipment in a given space,” according to Greg. Within this dance, architects are typically viewed as the instructor who leads the choreography that all parties, including vendors and technical specialists, come together and orient themselves around, ensuring everything jives together before initiating a transition to the next step.

The process begins with understanding everything from organizational drivers for a project, to budget and schedule, and eventually the details of where precisely to locate specific ports and receptacles. Options are often presented by the design team and in turn, design decisions are made in collaboration with stakeholders. Decisions typically build upon each other so it is important to avoid revisiting these choices later in the process, as they may affect other decisions and result in increased project costs and extended schedules. For example, an early decision to not accommodate individuals of size in a patient room can profoundly affect many aspects of the room if reversed at a later date. Room size increases, fixture and equipment revisions, redesigns of overhead infrastructure, additional structural elements, and door size revisions are among some of the immediate impacts of a seemingly small shift in direction like that.

Generally, project stakeholders will come to the table with specific goals: the patient demographic, the type of nursing unit, special equipment or services to be provided, bed counts. Sometimes those stakeholders have more subjective goals such as the creation of an inviting, home-like environment to put patients, family, and staff in a more relaxed mental state. For a lot of projects, combining technical requirements with more atmospheric elements is a challenge for the design team.

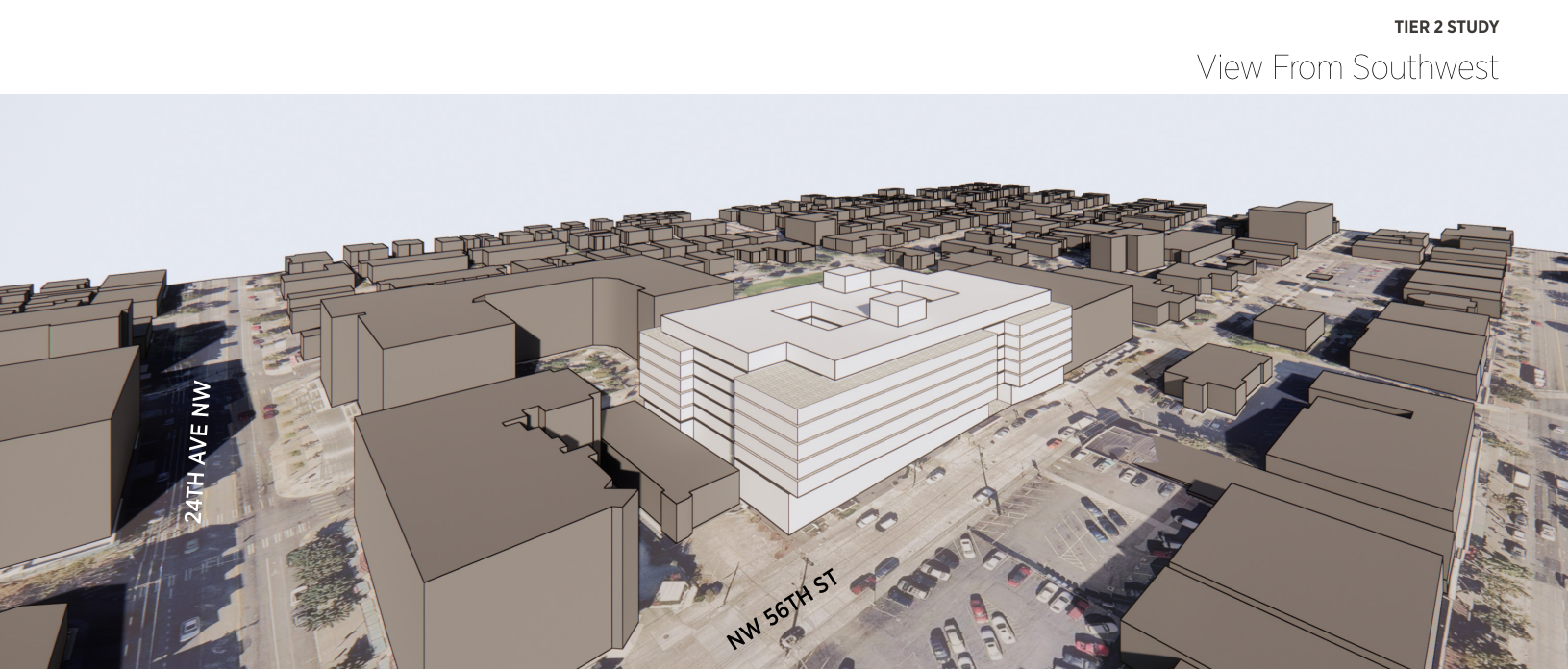

After defining the project goals, the programmatic ensemble – where things land within the space and how workflow will come together – comes next. This step entails deciding room formatting and purposes, as well as ensuring that all surrounding spaces are cohesive, and that their positioning makes sense for everyday use and workflow. The design team puts their best foot forward, creating drawings to illustrate the parts and pieces of the design, the rooms, the adjacencies, and the details that flow between those elements. A recent project for Greg and Hao involved a nursing unit at a local top-rated hospital that included typical nursing workspaces, nurse stations, clean and soiled rooms, and nutrition and hospital operations closets. This project also included 12 patient rooms that were to be completely demoed down to structure and built back to refinished space.

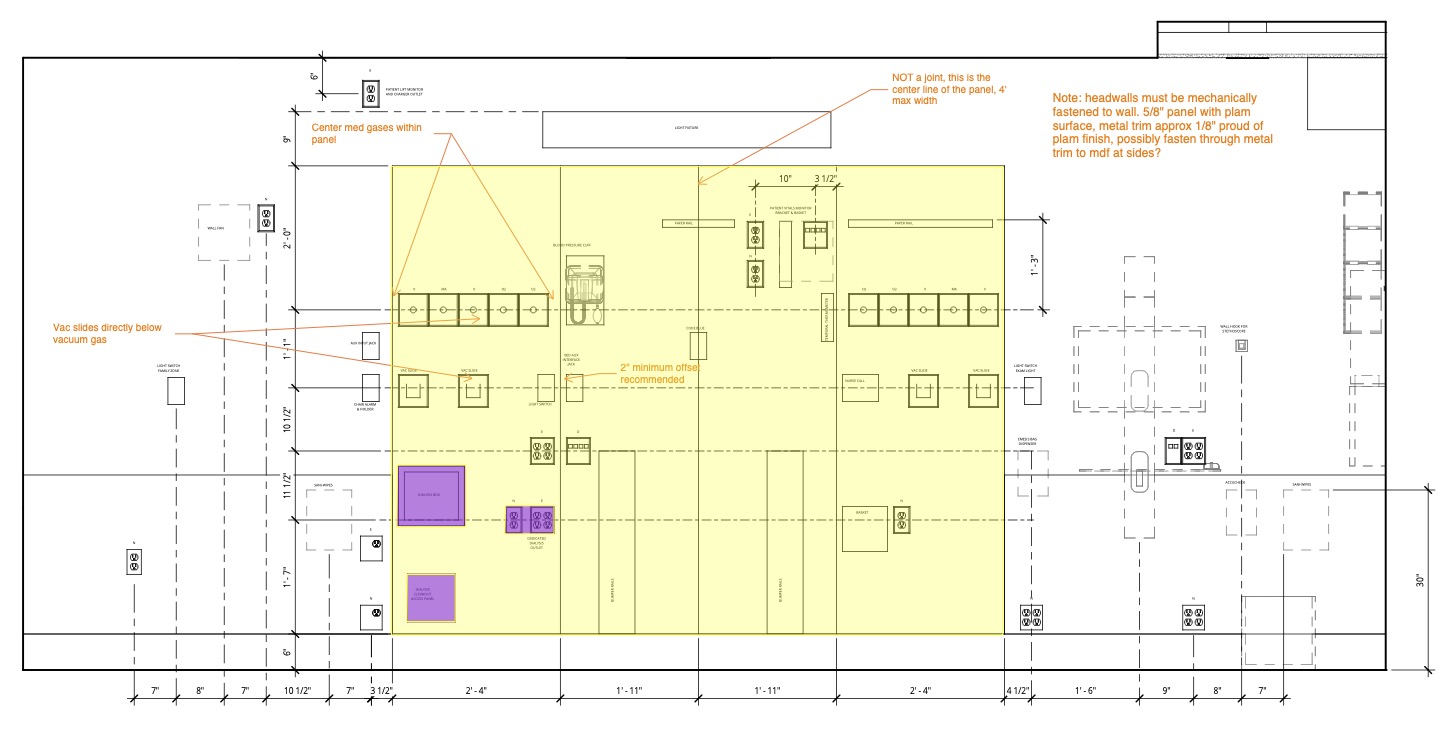

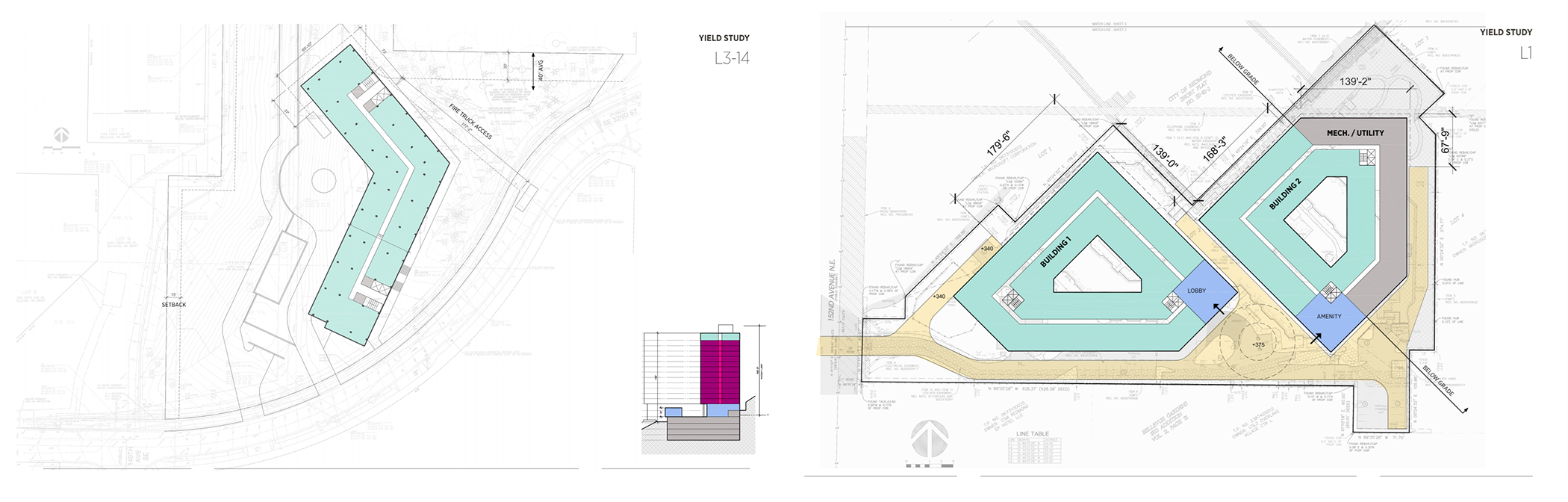

Example of the In-patient Wing portion of a programmatic layout.

The process of demolishing the two floors of the nursing unit down to the structure provided an opportunity to revisit all aspects of the design, adjacencies, and flow from a base level. The healthcare design team went through the process of redesigning the whole wing, meeting with the project team and client stakeholders to define the essential aspects of the project and establish guide rails to define their goals for the space. Since everything other than the structure itself was redone, the AMHC team took it as an opportunity to work on the nuances of each space within the larger unit, discussing the equipment and features needed in those spaces.

As healthcare teams move towards smaller details like the location of outlets or determining where nurse stations will go, they start “creating hardline plans and designating zones and elevations for where those things will be found,” explains Greg. An increasing amount of documentation is produced at this step, with an equally increasing amount of design effort and coordination spent to create them.

Up until this point, all design work, plans, interior elevations, renderings, and story boards have only occurred digitally. The design has not jumped into the real world. This point is important because not all project parties are versed in the reading of design documents or drawings. Often, a physical representation of the project space is needed for many to “see” the design.

Once the programmatic layout is decided upon, a mockup of the space is put together to share with users and stakeholders so they can ‘dance’ through the physical space and make overall adjustments to the design. This mockup can be basic or diagrammatic, as long as it represents each item that will appear in the final room format. Mockups can be cardboard, foam, or even real building products, with details represented by post-it notes and/or pictures of physical design elements. The project stakeholders and design team walk through the space to discuss and tweak those details. At the end of such a session, the design team is inched closer to reality and further documentation is created to record that status.

A patient headwall during a project space mockup.

Another element of this process that is unique to healthcare design is the many different types of equipment that need to be accommodated within these spaces. This is often a challenge in one way or another. Whether it involves replacing an old MRI machine or adding a new dialysis machine to a patient room, “there is always some nuance of the new equipment or required infrastructure that has changed over time,” claims Greg. “It never just plugs right in, and often the impacts behind the wall or floor or ceiling are not readily apparent.”

The required versatility of healthcare spaces and the differing technology requirements for those spaces necessitates more of the right people to be in the room to provide their thoughts on the given space’s design. “There’s a lot of technology with lots of requirements within a constrained environment which requires additional detail, additional organization, all that stuff,” says Hao. Having a wider range of end users in the space to provide their individual expertise during a design review ultimately results in a more well-informed project layout. “Everyone has a say,” Greg explains, “everyone has the ability to provide their input, because they have an inherent knowledge and expertise of what they do.” If we miss an opportunity to get the right people in a space to provide their feedback, it can open a door to additional setbacks for the project.

Greg and Hao reviewing a physical mock-up of a project layout.

The key players consulted in this process are all project stakeholders ranging from the primary client (e.g. owners or provider reps) to the facilities personnel and end-users (e.g. doctors, nurses, patients). Having a wide range of perspectives on how a space will be used helps the design team meet the needs of the final occupants and allows them to maximize the full use potential of a room.

Typically, once feedback on a design mockup has been received, the process begins again, starting by incorporating the new design suggestions and user needs provided by stakeholders. The design team continues to build upon their drawings and create further secondary documentation to illustrate the project design. Time and money go into these efforts every step of the way.

Project design diagram resulting from a mockup.

With stakeholder input, the design team begins the process of submittals and reviews with the authorities that have jurisdiction (AHJ), such as the Seattle Department of Health, for example. Most AHJs only want to know about certain required features, such as the number of outlets or receptacles, meaning that the space’s design can still be a work-in-progress at this stage since the actual layout really only matters to end-users and stakeholders. This can take weeks, if not several months, to work through. All the while, the design team builds upon the ever-growing stack of drawings to create a Bid Set for general contractors to provide bids, or a Construction Document if the general contractor is on the project team already. At this point, nearly 70% of the design team fee has been spent documenting – on paper – the designs created through the several iterations of meetings and review.

Process Challenges

There are challenges to this process, however.

Hao points out that challenges like “changes in frontline staff and leadership are fairly common in projects that take a year or more to complete. Each new person brings additional experiences and ideas that, if incorporated, may improve the design. But additional input from new individuals can have the adverse effect of creating more work or rework, increasing costs, and impacting the schedule.”

An example of this type of challenge occurred during a recent project that Greg and Hao worked on. At the stage of in-field box walks, facilities users and representatives for MEP operations showed up to participate in the physical review. As the first time seeing the result of the mockup drawings, MEP reps identified necessary adjustments to several features, including the dialysis box’s design and location, which requires specific types of plumbing accommodations to move. Since those facilities users had not seen the original mockup, the design team had to redesign the head wall to implement those requested changes, opening the floodgates for additional weeks and months of design adjustments and site visits. Multiple iterations of a physical install were required to gain approval from final facilities users and stakeholders.

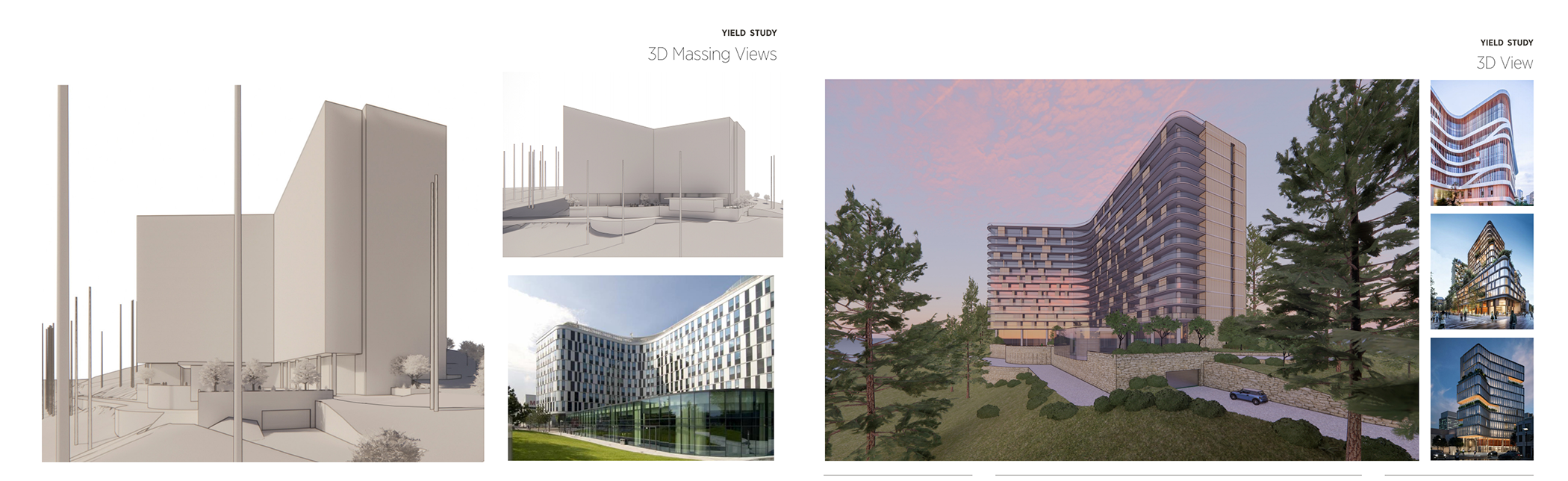

Snapshots from a physical box walk.

This demonstrates the importance of physical vs. digital or diagrammatic representation, with Architecture and Engineering processes existing largely in the latter. Combined with stakeholders that don’t 100% “read” or “see” the drawings or grasp the impacts that those details influence in the final product, there is a larger chance for information to slip through the cracks, requiring later revisions or adjustments.

Greg used the example of a dialysis service box – an in-wall infrastructure connection point for a dialysis machine – to explain this idea further. “Actual in-field location comes later in the design/construction process, before the facilities users can actually see a tangible example. Alterations at that stage can change the whole headwall. Movements to the box location to accommodate behind-the-wall plumbing changes the flow of the bedside, and it changes all sorts of other stuff, also behind the wall.” This means that the traditional linear documentation process takes on yet another iteration of design as all the components are fit and re-fit into the final physical space.

A dialysis box headwall that has had location adjustments following the initial box walk. Note the two dialysis boxes side by side – the one on the left is ‘moved loc.’

Because hospital rooms have all kinds of ports and receptacles, especially at headwalls, for both patient and staff use of equipment, the largest aspect of the challenge in designing these spaces is ensuring that those ports and receptacles are in the correct and most opportune position for everyday use. Electrical outlets, medical gas outlets, low voltage data outlets, equipment rails, workstations, dialysis boxes, and even in-room furniture like chairs or the patient bed are intertwined in a dance with each other in this way. Adjusting one often entails adjusting the rest. The real issue arises, as noted above, when the location or adjacencies of these ports and receptacles are indicated on design drawings in ways that can’t be visualized or understood by critical stakeholders. This can lead to things being missed or overlooked during drawing reviews that remain undiscovered and unaddressed until the rough-in stage is complete and box walks are done in-person.

Additional challenges that can complicate and prolong the design/construction process include the rapid pace at which medical equipment or its interface with the built environment, as well as the hospital code or construction requirements for those pieces of equipment, advances and evolves. Greg summarizes the issue, stating how “certainly over time, codes can change, particular equipment can change, the technical requirements or even the detailing requirements desired by a facility – the lessons learned from real world installations – for some of those essential elements, can change. That change or request can impact a longer-duration project, as those code changes or equipment changes throw off progress that has been made.” During the long project timeline, requirement changes or stakeholder requests can necessitate document changes in the drawings and potentially in the AHJ process that is already spinning away.

Requested changes to detailing and installation for the dialysis service box itself (not just the location) can necessitate alterations to the documents and submittals that brought the project to this skeletonized, built form. AHJ submittals need adjustments that require dialog with reviewers and ultimate buy-off on the new final product or install. The stakeholders requested a more robust installation for their new dialysis boxes, and those improvements were made during the active construction period, rather than during previous design phases, and based on lessons learned from previous projects. In this particular case, a change to the dialysis service box placement and detailing extended the project schedule by over one month, triggering many meetings and incurring budget impacts in excess of $100K. Ultimately, the project’s go-live date was pushed out farther into the future than originally planned, resulting in concern and frustration by hospital leadership.

Both of the situations noted above influenced the project’s schedule and budget. Additional time and costs are added with every change to the previously drawn documents in the prior design phases.

“Even though the process is multi-layered, it’s never going to be perfect,” Greg admits. However, just because the process will never be perfect does not mean it isn’t worth improving.

Solutions

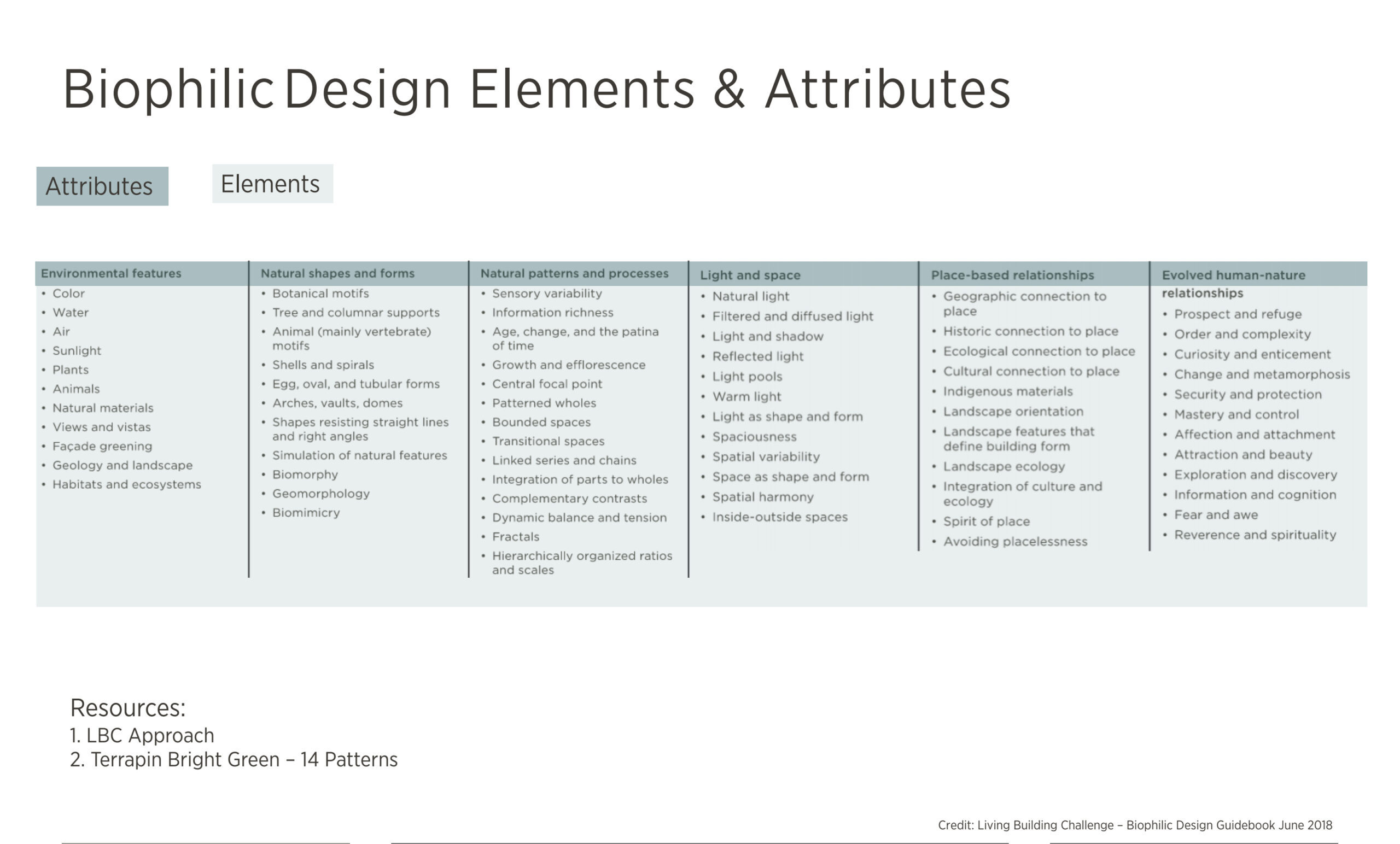

Greg and Hao identify a few solutions embraced by the industry that address the primary challenges of the typical design process, such as changing staff, changing equipment and code, and extended timelines and budgets, among others. The solutions they employ range from the ‘big room’ idea where everybody is collocated in the same place to discuss everything both big and small, to the ‘design workshop’ idea, where the design process is more like a sprint from start to finish within a set amount of time. Both solutions occur early in the design development phase with the goal of solidifying all the details, parts, and pieces of a project, setting those decisions in stone, not to be revisited.

“There are some things that have been tried by other firms that have not been considered standards, and then there are other things that have evolved standards but are not yet adopted,” Hao clarifies, indicating that there is no one-size-fits-all solution for the challenges faced by Ankrom Moisan’s healthcare team.

A lot of the proposed solutions are in no way new ideas for Ankrom Moisan. “It’s one of those things that has been there from the beginning of time, and we just keep trying to improve upon it and make tweaks to our process individually and as a team and as a firm that might differentiate us from others,” Greg explains. “Most solutions implemented follow a traditional design process timeline and cadence, meaning they are enacted early-on, before real, physical field work has been done on a project.”

Ultimately, Greg and Hao are trying to reorganize the early design documentation process to streamline the efforts of the project team and schedule, preventing re-work and safeguarding time and fees in the process.

In terms of making this a reality, the AMHC team intends to dedicate time and effort toward creating templated lists and details of requirements to be shared with stakeholders and end-users early in the design process. Having those templates on hand allows the project team to quickly vet those requirements for a given space with the stakeholders and end-users, and can therefore make headway on the design process for other spaces and areas of the project instead of focusing on the minutiae of the exact location of headwall ports and receptacles, for example.

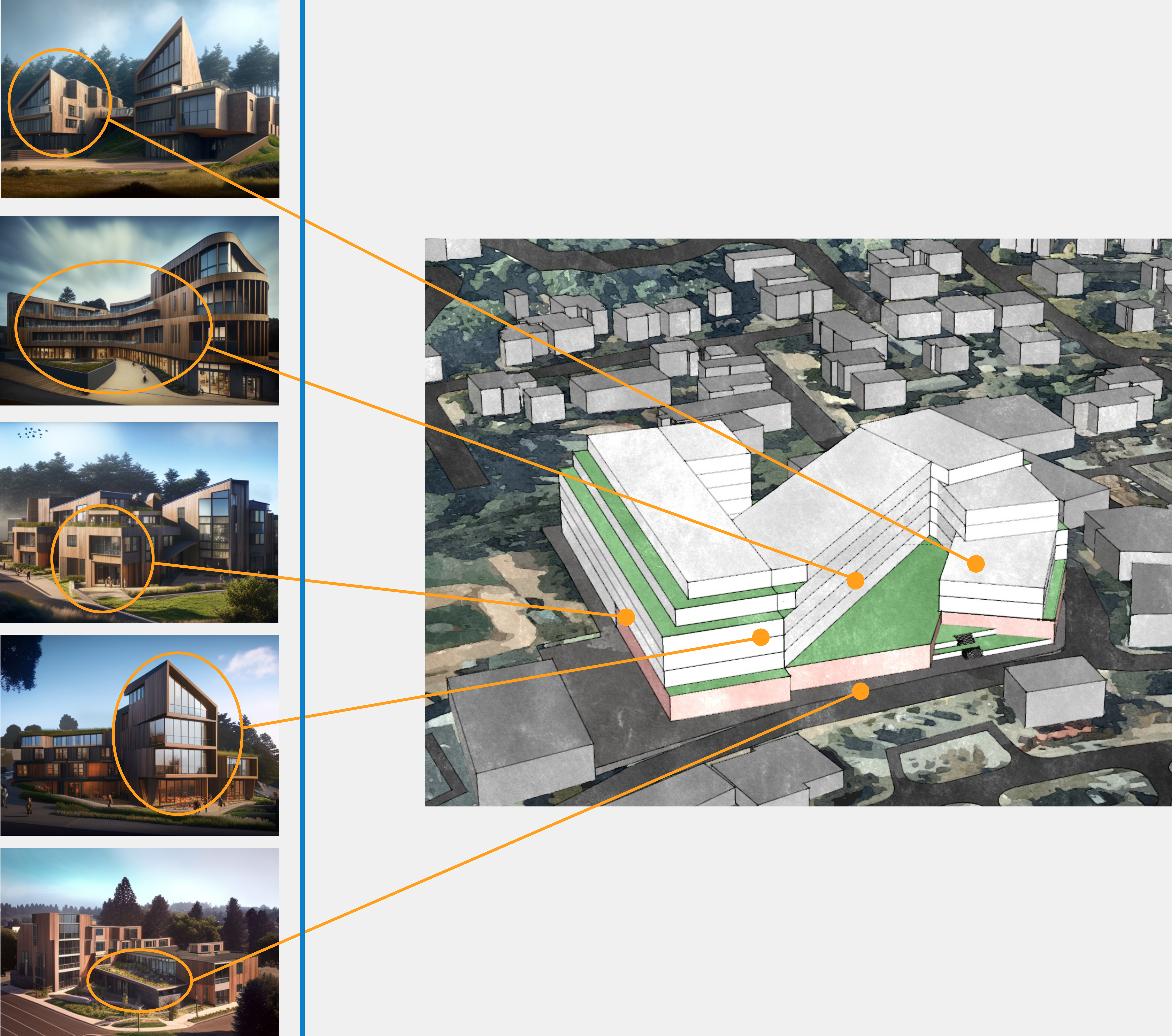

As noted earlier, AHJs don’t necessarily need to know the exact location of a headwall element, and headwall elements don’t necessarily need to be drawn on the documentation. What the AHJs do want to see is that certain ports, receptacles, and quantities will be present at the project’s conclusion. The design and construction teams inevitably provide AHJs that information through inspections and record documents of those final locations. In this example, what Greg and Hao propose is diagrammatically designing the headwall for the purpose of stakeholder design intent sign-off and AHJ approval to begin construction, therefore continuing overall project cadence and momentum, moving those decisions and location changes from the drawn world into the physical. “We’re trying to prevent re-work by pushing those decisions into the built environment, which is more tangible to the everyday end-user than a set of technical drawings,” Greg reveals. The permitting documents can serve as a scaled-down design package that provides the necessary information for the AHJs initial approval for go-ahead into construction.

Once into the physical construction, the build and design teams produce the skeletonized headwall and can finally “see” locations and adjacencies. Project stakeholders and end-users typically participate in this review to “see” design solutions in a tangible form. After these reviews take place, the design drawings are finalized with the locations and dimensions of ports, receptacles, and equipment that will be provided to AHJs and submitted as a project record.

Final iteration of the diagrammatically-designed headwall assembled by Greg and Hao.

Solution Impacts

Greg summarized the impact of implementing these changes to the current healthcare design process, saying that it would be “an opportunity to get our arms completely around the large aspects of a project early on to ensure the linear design process keeps moving and advancing.” This is significant when trying to prevent backwards steps, as those backslides cost more time and money in the long run. “We’re always trying to have steps going forward so that every time we go to a new phase or the next step, the smaller details we incorporate build upon the existing design.”

Another positive impact of incorporating these changes is that projects can adhere to existing budgets and schedules without as many design iterations and backwards steps. “A lot of times with our clients, our stakeholders, they’re worried about getting a project open and operational to provide services as quickly as possible.”

Overall, a revision of current design processes to be more streamlined and efficient will have positive impacts on the design teams that create healthcare projects, as well as the owners, clients, stakeholders, and end users of those projects. It’s a win-win solution that establishes choreographed design and construction processes to secure the momentum and success of our healthcare work.

In the end, once the shuffle of design and detail coordination is over, these choreographer architects can lace up their shoes and begin participating in the dance of bringing their essential healthcare projects to completion.

AM is Sketchy is an informal seasonal weekly Lunch & Learn, BYOL (Bring your own lunch), hybrid art session led by Jason Roberts and Roberta Pennington. Method, inspiration, and sketchy results are shared with fellow AM artists.

AM is Sketchy is an informal seasonal weekly Lunch & Learn, BYOL (Bring your own lunch), hybrid art session led by Jason Roberts and Roberta Pennington. Method, inspiration, and sketchy results are shared with fellow AM artists.