The Do GOOD / Be WELL scholarship encourages Ankrom Moisan employees to research an open-ended topic of their choosing to discover and share the practical results of their findings with the firm, industry, and community at large. The scholarship, started in 2017, is sponsored in memory of former AM employee Carolyn Forsyth, an inspirational leader and unyielding force for change. Intended to honor her legacy of sustainability, equity, innovation, advocacy, education, and leadership, the DGBW scholarship elevates and empowers new and inspiring ideas within Ankrom Moisan and the broader field of architecture, pushing us all, as the name implies, to do good and be well.

For their research scholarship, Amanda Lunger, Elisa Zenk, and Stephanie Hollar ventured to ask: Where are the Women?

Amanda, Elisa, and Stephanie atop Ankrom Moisan’s Portland office.

The idea came to them naturally. During the firm’s 2020 Women’s Day celebration, Elisa noticed that some of the AM statistics shared didn’t seem to tell the whole story. “The women in architecture numbers were getting buried in the celebration of the fact that our office had this large percentage of women,” Elisa explained, “but when we looked into it, most of that percentage was made up of women in the interiors department and various overhead positions.” The real number of women in architecture was not as equitable as it could be. “I think I already knew this intuitively, that women are underrepresented in design roles,” Amanda disclosed, but “once we actually looked at those numbers, that was kind of shocking to me.” Stepping back to all architecture roles, not just design, women only make up 37% of architecture staff nationwide, according to AIA industry data collected in 2019. Amanda, Elisa, and Stephanie all knew that there should be more women in the industry and began to question why that was not the case. They were also interested in solving that problem at our firm, pushing AMA beyond industry trends.

After Amanda, Elisa, and Stephanie discussed this observation, they agreed that they had seen too many brilliant women, presumably on track for leadership, leave the field. “We were talking about these women who were really rockstars in the architecture department who were leaving,” recalled Amanda. “We were speculating as to why the industry seemed to have that problem.” Whatever the cause, it was clear that some women were dissatisfied with their experiences in architecture.

Stephanie recognized that the issue of women in architecture leaving Ankrom Moisan for other opportunities was one that needed a deeper investigation. It was also a problem that affected her directly. “The women who we saw leaving at that time were older than me and in architecture, but then they left. I saw them as people that I was looking up to [that] were mentors and having them leave really created a gap of future women architecture leaders,” she remarked. “It makes you kind of question your own career sometimes. Like if all these other women are leaving, it’s like, OK, what am I doing here? Like what are they finding elsewhere?”

In fields traditionally dominated by men, like architecture, same-sex mentors are paramount to the success of early career women. Female designers are more likely to aspire to career advancement if they see someone like them at the top. This role-modeling is critical for the retention and professional growth of our talented female architects.

The consequences of the lack of female representation in architecture was further emphasized by Amanda, “Being a woman in architecture, I’ve run into a lot of experiences in dealing with colleagues where I felt very misunderstood and kind of lonely as being a gender minority or marginalized gender in this industry. I’ve had personal experiences sitting in a meeting with consultants and some of my project team members, who are all men. At the beginning of the meeting, they’re all talking about working on their cars, or fishing, like these shared hobbies that they have. I had a hard time finding common ground. It was hard to know where to start [building rapport] in some of those cases. I felt like I got overlooked a lot of the time.” Elisa felt similarly, noting how being the only woman in the room “makes it hard to have a voice or feel comfortable having a voice. There’s not always room at the table, even if you’re sitting there.” Elaborating on this idea, Amanda reflected, “I feel like I was always looking for a woman who had been in that position before and could give me advice like how to cope and how to get through it. But those mentors just weren’t there.”

The exodus of women from established architecture firms becomes even more lamentable once one recognizes that the leadership positions and characteristics women tend to embrace are critical for the future success of the firm; roles and traits such as “inspiration, participative decision-making, setting expectations and rewards, people development, and role modeling” (McKinsey, 2018). Simply put, a workplace with more women is a workplace with more creativity, productivity, and profitability (MIT News, 2014). The lack of women in architecture is intrinsically detrimental to everyone in the industry.

The healthcare team working together in the Seattle office.

Amanda, Elisa, and Stephanie’s interest in what happened to these women came at the right time. It was about a week before applications for the Do GOOD / Be WELL scholarships were due, and after their initial conversation, Amanda thought, “maybe we should turn this into a research project, that way we have time set aside to really look at it. I mean, nobody else was doing this research, so it kind of felt like, well, if we don’t do it, who’s going to?” The group quickly put together an application and submitted it before the April 2nd deadline, a date shared with Carolyn Forsyth’s birthday.

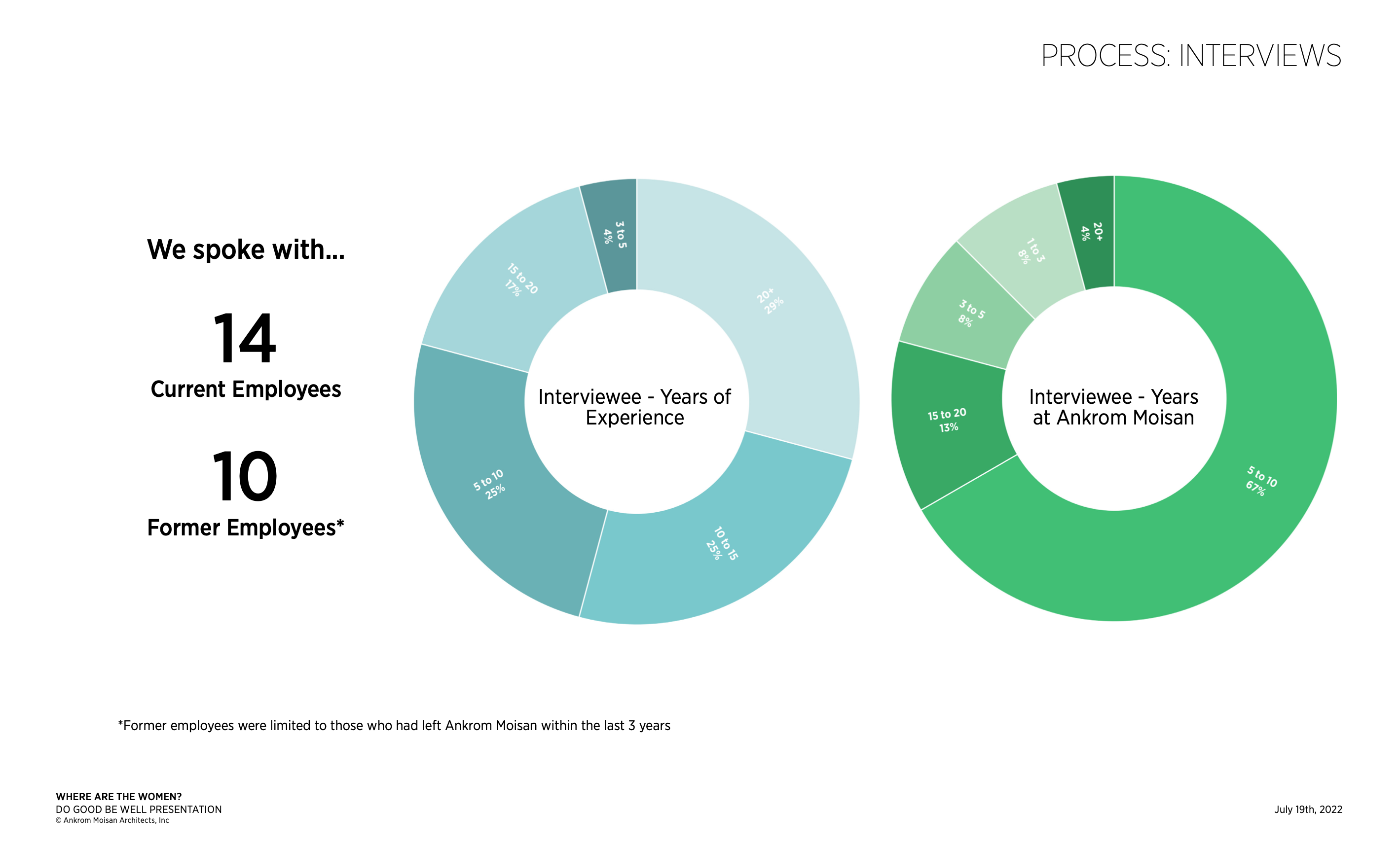

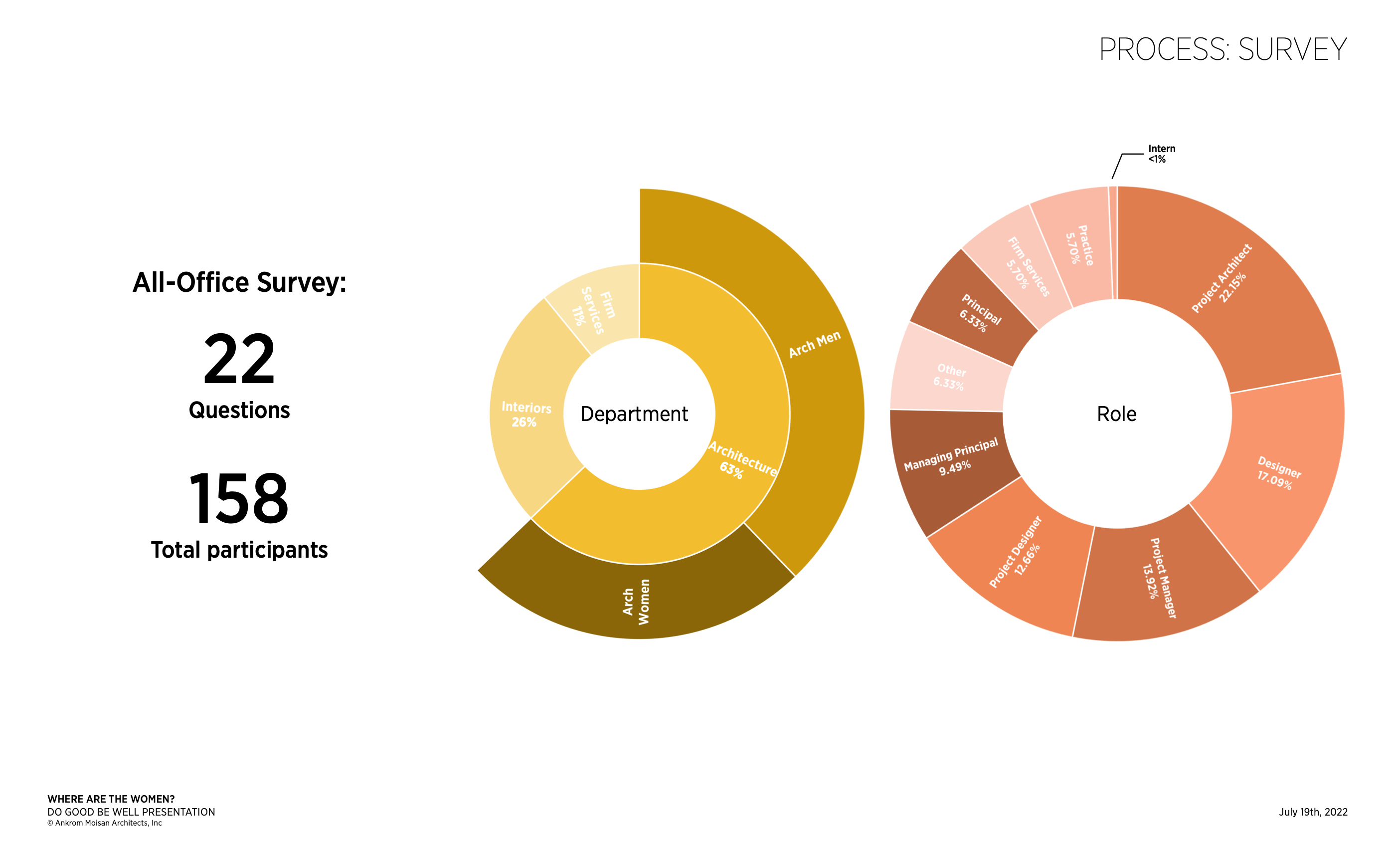

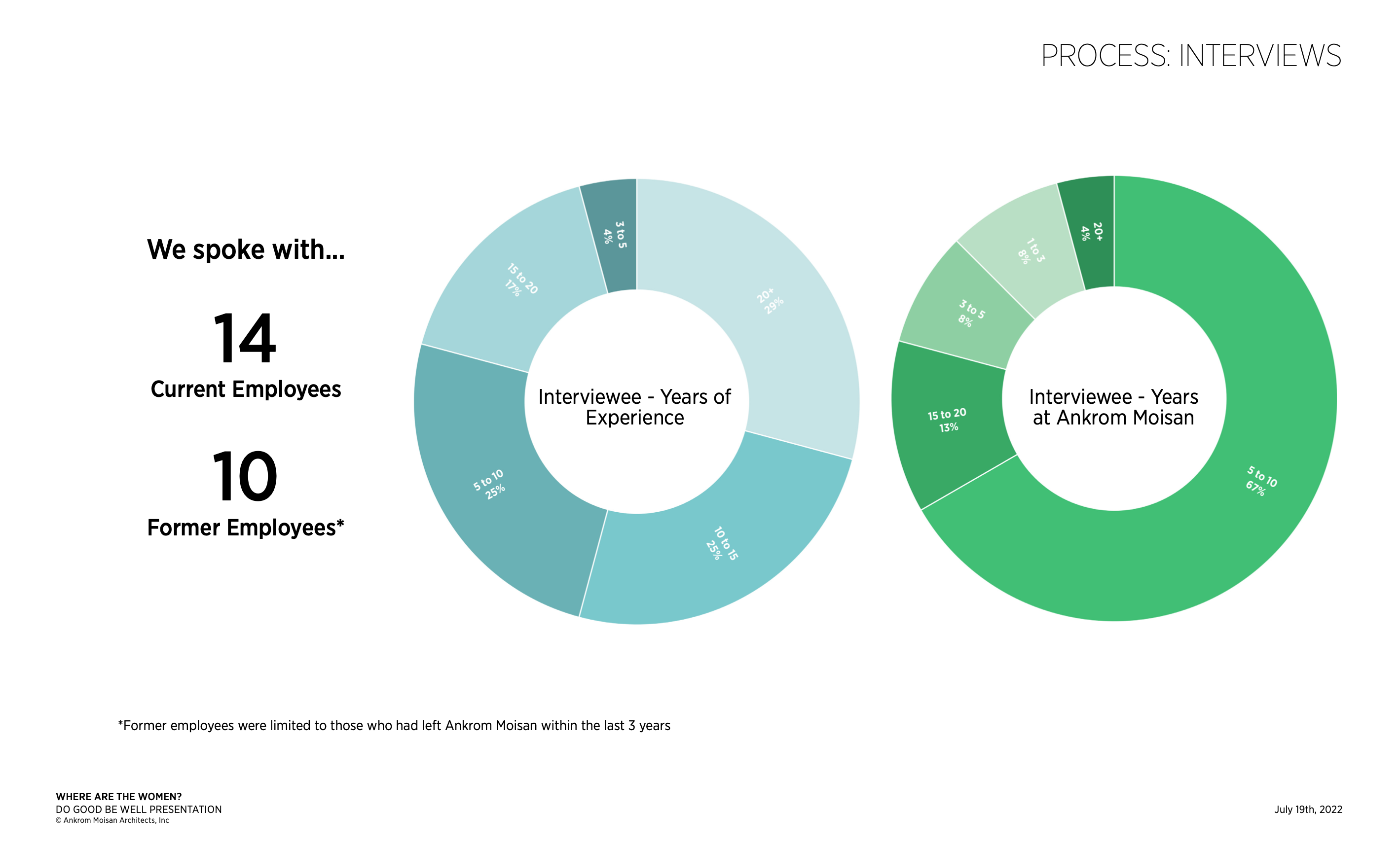

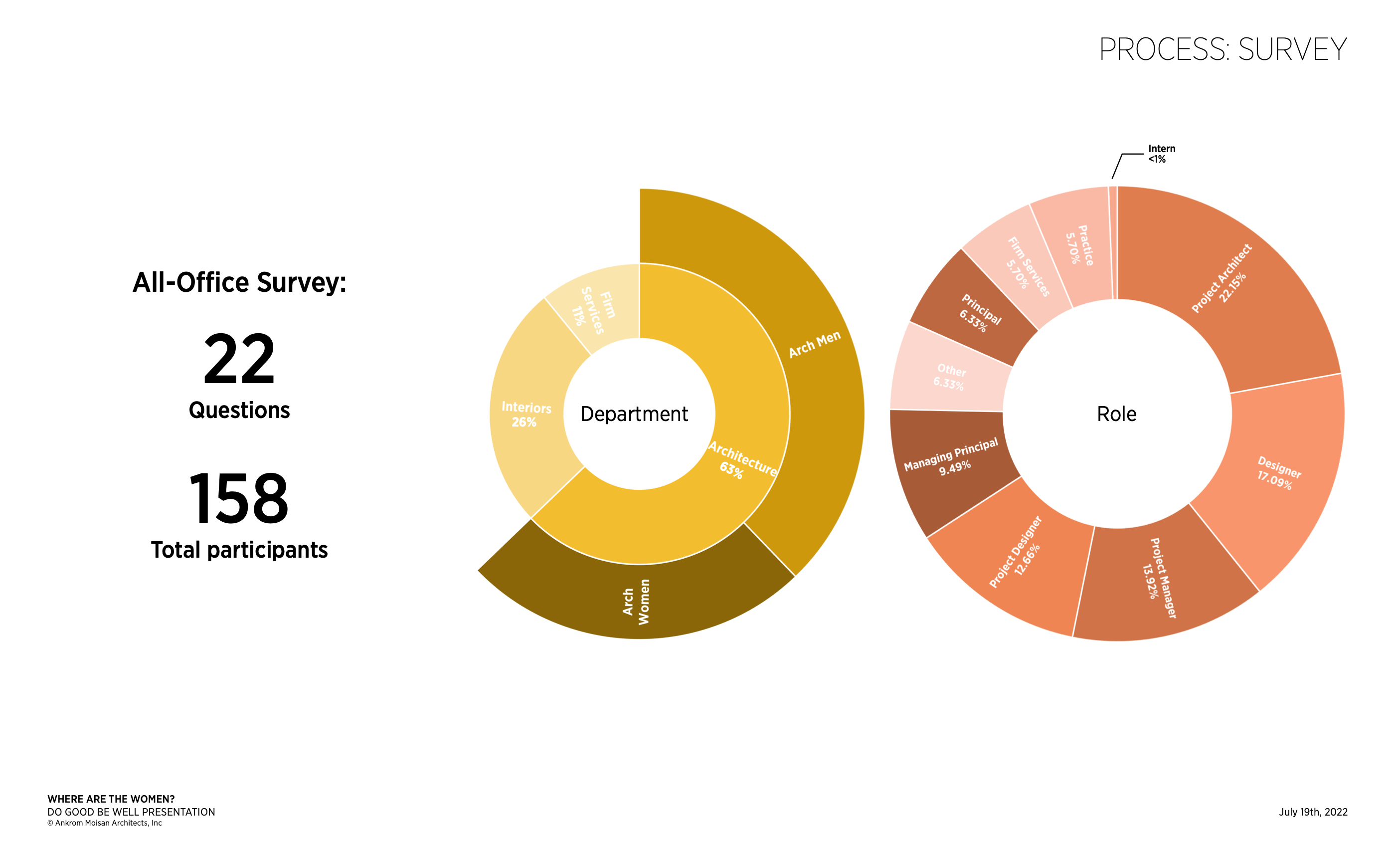

Many of the data points collected during the project’s research were gathered from conversations with women architects about their professional experiences, career goals, the tools that helped them succeed, and what they thought firms could do better to support their growth. Additional observations came from personal experience, while other statistics were sourced from the AIA. The bulk of Amanda, Elisa, and Stephanie’s AMA-specific statistics originated from a firm-wide survey they conducted, which gathered responses from 158 participants, both male and female.

Graphs illustrating the research project’s interview and survey process.

Stephanie disclosed that the study they conducted was designed to provide “specific points that we could apply here at Ankrom to help [combat the disappearance of women from architecture].” The idea was that by identifying the roadblocks that women face when advancing in their careers, they will be able to more confidently advocate for themselves and the resources they need to grow as professionals. The research is an important first step in Ankrom Moisan’s journey to bringing gender parity to the architecture department and increasing diversity, equity, and inclusion in the firm overall.

Read part two, here, to learn more about what the research uncovered.

By Jack Cochran, Marketing Coordinator